From the Gropius House to Our House

By Carrie Greif, WPAMC Class of 2019

First Edition of Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House. Farrar, Straus & Giroux: 1981. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

By the time the Northern trip rolled around, I was deep in the thick of researching modernism in America for my upcoming thesis project on the previously undocumented mid-century modern furniture collection at Winterthur. I’d been cycling through a slew of influential texts that herald the philosophical and sartorial splendor of modernist design. Strangely the text that stuck in my mind the most, and the one whose clever prose made me tear up with laughter, was Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House. In Wolfe’s seminal work, his classic style of brilliant skewering is employed to bring postwar modern architecture in America to trial. Wolfe argues that modernist ideology has placed greater value in cult-like, philosophical visions of design than the needs of the people using and inhabiting its spaces. Modernist architects are framed as self-righteous characters who foist their “non-bourgeoise” design principles on a populace that the designers see as desperate and naive. In Wolfe’s world, designer architects like Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer and Josef Albers designed more for their own anti-elite philosophical egos than the people their designs were intended to serve.

It is hard to choose the modernist architect most abhorred by Wolfe. But, if one had to pick, it could very well be Walter Gropius, whom Wolfe calls “The Silver Prince” and “White God No. 1.” Gropius is given this special ire because he is portrayed as the fountainhead from which modernist design was pumped into America. Wolfe states,

“To the young American architects who made the pilgrimage, the most dazzling figure of all was Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School. Gropius opened the Bauhaus in Weimar, the German capital, in 1919. It was more than a school; it was a commune, a spiritual movement, a radical approach to art in all its forms, a philosophical center comparable to the Garden of Epicurus” (8).

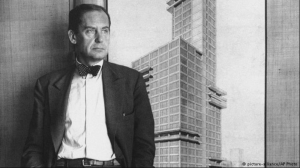

Walter Gropius, c. 1924. Image courtesy of alliance/AP Photo.

Wolfe faults Gropius for the establishment and clout given to modernist designers in America. Gropius is the embodiment of the anti-elite philosophy turned into elite designer; this is the main modernist paradigm with which Wolfe takes issue. Though modernist architects touted a revolution for better life through design, modern architecture was not as beloved as its creators projected it could and would be. Wolfe documents how the public saw many of these nearly puritanical buildings, constructed from glass and steel, as impractical and uninhabitable.

In 1981, when Wolfe published from Bauhaus to Our House, modernism had fallen out of fashion. Over 30 years later, it is back in with millennials, such as myself, falling adoringly into the forms, philosophy and preaching of modernist designers. With quotes like, “Only work which is the product of inner compulsion can have spiritual meaning,” how could one not be enchanted by Gropius? There is so much earnest hope in his writing and a belief that things can get better through design in spite of the global horrors that shaped his life. But in reading Wolfe’s interpretation, I began to agree that the theory often outweighed the craftsmanship and caused a problematic shift in American design, and so I was stuck in a complicated bind of interpretation…

Gropius House in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Photo by the author.

Until the Northern trip, that is, when I was able to explore the belly of this beast with a tour of the Gropius House. In 1937, Walter Gropius and his wife Ise arrived in the US virtually destitute after leaving most of their possessions behind as they fled Nazi Germany. Gropius designed his family home to be an exemplar of his philosophy. In Gropius’s own words, he intended for the house to be, “The small house of Today… to be built of light construction, full of bright daylight and sunshine, alterable, time-saving, economical and useful in the last degree to its occupants whose life functions it is intended to server.” It was the perfect place to see modernism’s intentions and to compare them with its outputs.

Saarinen Womb Chair in Gropius House Living Room, photo by the author.

It was hard not to experience the house with the same awe of a child in a candy store. With the seemingly effortless placement of prints by Joan Miró and Henry Moore, Alvar Aalto vases, Saarinen womb chairs, and countless other incredible objects, the house felt like a special treat. Gropius structured the space to cultivate impactful moments and visitors can feel that in the details. The windows were expansive, with light carefully pouring into every corner, and the “small house of Today” felt spacious and contemporary. Furthering the delight was experiencing the impact of the care taken in preserving the interior objects, textures, and colors. The Gropius House felt authentic and genuine because its current iteration is true to Gropius’s vision. The house was a total work of art in a way that was utterly distinct from the other 17th, 18th and 19th century interiors we were able to experience on our trip.

Alvar Aalto Vase in Gropius House Guest Room, photo by the author.

But, it is also very clear that this is a special space that is distinct from the vast majority of modernist buildings. The home itself operated like a showcase, and for an architect/designer interested in eliminating the bourgeois aesthetic, it was full of incredibly high-end objects. Though the many elements of the architecture itself, from the brick chimney to the vertically oriented redwood white-painted clapboards, were not elite objects, it was clear that the total home was an elite entity. The house was relatively small but it was rich with ornament and expensive flourish.

Photograph of the balcony’s roof at the Gropius House, photo by the author.

We live in a time when a lot of content is divisive. The battle lines are drawn, sides selected, and arguments defended until the bitter end. Experiencing the Gropius House did not eliminate any of the contradictory ideas I had harbored surrounding modernist design. If anything, touring the house further solidified my impression of the dichotomies between modernist design intentions and actualities. Being in the house allowed me to see how you can appreciate something while fully acknowledging its shortcomings. And that’s something worth experiencing.

Leave a Reply