Ceramics: A More Complex Social History

Every January, the first-year fellows of the Winterthur Program and several students in MA and PhD programs from the University of Delaware take part in British Design History: a three-week course on design and material culture with one week at Winterthur and a two-week field study in Great Britain. Traveling to cities including London, Stoke-on-Trent, and Bath, the students have an opportunity to study American Material Culture within a greater global context. Students’ posts in this section are centered on their experiences in England or working with British objects in the Winterthur collection.

Ceramics, in some form or another, were seen at essentially every historic site we visited during our British Design History course. As the trip progressed, I found myself wondering why that was the case. After some reflection, I came to the conclusion that ceramics – wares used for eating and drinking, in particular – are familiar to everyone. As a graduate student, I know that I wake up every morning and pour myself a cup of tea or coffee in my favorite ceramic mug, eat cereal out of a ceramic bowl, and eat my lunch and dinner off of ceramic plates. With rapid expansion of the British ceramics industry in the 18th century, affordable ceramics became integrated into the everyday lives of people in the past and are still used today, centuries later. However, when we sit down to a meal, or have a cup of coffee, we do not necessarily think about how our favorite mug was made, by whom, in which factory, or expect it to be served to us by a servant or enslaved worker.

Visits to sites like Middleport Pottery enabled us to get a better understanding of how the ceramics we had seen on our trip were made, who did the making, and the sometimes-dangerous conditions in which these individuals worked. For example, in order to make lead glazed earthenware, the individual doing the glazing would have been exposed to high quantities of lead, shortening their lifespan by decades; bottle ovens, used to fire ceramics, crumbled with workers inside, killing many, and the pollution from the kilns was a large public health risk; children were sometimes up before dawn to begin their work at the treacherous factories.

After this visit, I never saw the ceramics on display at other museums on our itinerary, such as the Wedgwood Museum, or Brunel’s SS Great Britain, as representing aesthetic and economic value alone. Their history is too deep, too complex.

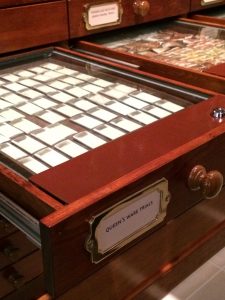

A drawer full of Josiah Wedgwood’s trail for creating the correct color for his Queen’s Ware at the Wedgwood Museum.

Brunel’s SS Great Britain has a very elegant replica of a first-class dining room laid out for visitors to experience. However, the people who purchased Wedgwood ceramics, or ate in first-class on the SS Great Britain, had very different life experiences than the workers who made the ceramics they ate from during mealtimes and the passengers in second and third class. These individuals were most likely served their food on expensive ceramics by free or enslaved maids, butlers and other service staff.

Multiple-course dinner service set on a long table for the first-class passengers of Brunel’s SS Great Britain.

This is especially true for British ceramics involved in the Atlantic Trade. Downton Abby and Upstairs, Downstairs do a fairly good job of teaching the general population about social class and status in Britain. However, not all ceramics were made for internal use: some were shipped over to the Americas and the Caribbean. Just who was doing the serving, or cleaning the wares after a meal in these places? Enslaved laborers? Indentured servants? Depending on time and place, the answer varies. However, it adds another layer to the history of British ceramics—one that spans continents. The next time you visit a museum, or even Winterthur, try thinking about the people who made the antiques and artifacts you are looking at, and begin to look at material culture from different perspectives – the maker, the consumer, the help, the collector, the museum curator. What does each plate, each glass, each chair mean to all these different individuals? Which stories would you choose to tell?

[Image from Winterthur]

By Alexandra Rosenberg, WPAMC Class of 2019

Leave a Reply