How a Swiss Artist Showed Me Material Culture Through Prints

Throughout the first year as a Winterthur Fellow, the Connoisseurship courses allow us ample opportunities to pursue interests we had before beginning the program as well as explore new objects and topics. I was very excited to approach a new topic during our Prints Connoisseurship block at the end of last year: printmaking and the American West. While we hear countless stories about Lewis and Clark and the artist George Catlin traversing the Missouri River, we seldom hear about Carl Bodmer, the Swiss artist who accompanied German naturalist and Prince Maximilian Wied on his 1832-34 expedition into modern-day Montana. The only artist to have traveled this far up the Missouri, Bodmer captured some of the most significant images of the Mandan peoples of the Upper Missouri that still exist today.

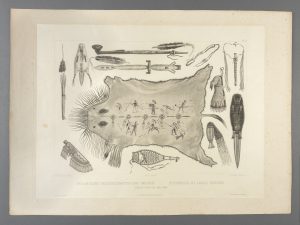

Carl Bodmer, “Indian Utensils and Arms,” from Bildatlas, second state aquatint, Leipzig edition with hand-coloring, 1922, Leipzig, Germany. Winterthur Museum 2016.27.2.

The prints which were my subject of study for this project were two iterations of a series of 81 distinct images made for publication in a Bildatlas (Picture Atlas) intended to accompany the Prince’s first-hand journals of their expedition. The expedition spent a particularly cold and harsh winter with the Mandan people in modern-day South Dakota, where Bodmer and the Prince had unique opportunities to live alongside the Mandan and experience their daily life. As nearly all the Mandan were killed by a smallpox epidemic only a few years after Bodmer left, his drawings, paintings, and prints provide one of the only primary sources we have to understand the intelligence, beauty, and resilience of the Mandan.

Carl Bodmer, “Indian Utensils and Arms” from Bildatlas, first state chine collé print, 1839-1843, Paris, France. Winterthur Museum 2016.27.1.

Both the hand-colored and black-and-white versions of “Indian Utensils and Arms” illustrates the close relationships Maximilian and Bodmer developed with one of the Mandan specifically: Mató-Tópe. Bodmer and Maximilian became very attached to the respected chief, warrior, and medicine man; their fondness for Mató-Tópe, and for many of the other Mandans and Hidatsas they met, is clearly demonstrated in this print. Its combination of artifacts not only contributed to 19th century scientific knowledge of Native Americans and their customs, but also reflected a deep respect for the people who used these objects. Although the tools included lack descriptive context in their original publication, Maximilian’s journals and the realistic nature of Bodmer’s artistry allow us to understand the American frontier and the manner in which artists from Europe and America interacted with it.

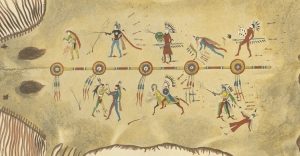

Most of the objects depicted in “Indian Utensils and Arms” belonged to Mandan women and men, including the buffalo robe at the center. Mató-Tópe painted the seven scenes on the robe himself, depicting some of his triumphs in battle. Bodmer painstakingly drew the robe exactly as he saw it – and exactly as he drew every other person or object throughout his two years in North America.

Close-up image of the battle scenes painted on Mató-Tópe’s buffalo robe. Traditionally in Mandan culture, men would paint pictorial images and women would do geometric work. Robes such as this one was both a symbol of power and a way to connect with other people through storytelling. Image courtesy of the Winterthur Museum.

While Bodmer never returned to the United States after this expedition, he never forgot his comrades along the Missouri and often remarked that “Over there, I had friends.”[i] His insistence throughout the publication process of the 81 prints in the Bildatlas was not simply an artist’s obsession over controlling the process; it was about the faithful representation of people he respected and loved. Even though the objects depicted in “Indian Utensils and Arms” were from Mandan and Hidatsa peoples and not distinctly labeled as coming from one person or group or the other, Bodmer’s affection for the people who helped him survive the winter of 1833 remains apparent in the detailed representation of their material culture.

While having these prints in Winterthur’s collection may seem somewhat incongruous, they are an asset to anyone studying material culture and American art. By a Swiss artist who admittedly spent his happiest years in the interior of North America, these artworks enable students and museum visitors to have a more thorough understanding of what is meant by American Material Culture: not just things made by Euro-American craftsmen on the East Coast; not only the beadwork or pottery of Native Americans in the Midwest and Southwest; but also paintings, drawings, and prints made by people who understood the interconnectedness of all cultures and humans living in this world.

In addition to these two versions of “Indian Utensils and Arms,” Winterthur acquired five other prints from Bodmer’s oeuvre in 2016. To see additional images, please visit the Museum’s online collections database here.

By Katie Fitzgerald, WPAMC Class of 2019

[i] Robert J. Moore, Native Americans: a portrait: the art and travels of Charles Bird King, George Catlin, and Karl Bodmer, 203.

Leave a Reply