There’s More Than One Way to Make a Chair

Most problems have more than one possible solution, and the artisan’s perpetual query of “what’s the best way to make this?” is no exception. As a craftsperson myself, I’m always intrigued by how other makers solve their problems. Connoisseurship classes at Winterthur provide me endless opportunities to explore this by analyzing some of the more technical aspects of the objects we study.

We first year fellows have just completed our furniture connoisseurship block. Since September, we’ve been meeting with curator, Josh Lane, and learning the ins and outs of furniture construction, style, and of course, wood identification. Hopefully we’ve learned the difference between walnut and mahogany; gained a newfound respected for what distinguished Queen Anne and Chippendale styles (along with the understanding that sometimes style labels are just labels!); and leaned to discern the difference between chairs made in Boston, and those constructed in Philadelphia.

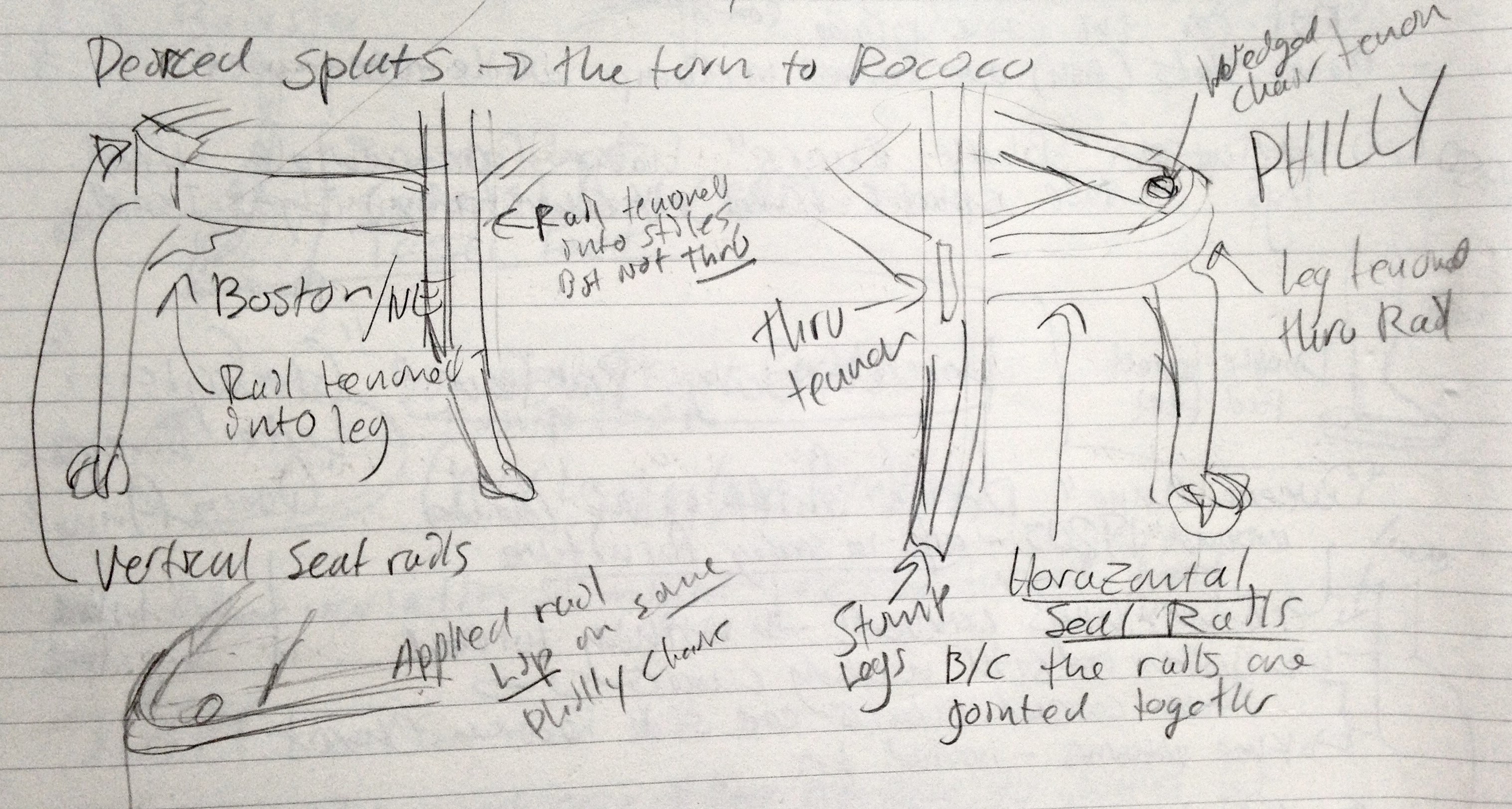

Image: The author’s furniture connoisseurship block notes with hand-drawn illustrations comparing Boston and Philadelphia chair construction. The page contains drawings of two chairs, with labels indicating the parts and the joints with which they were assembled.

What exactly do we learn from knowing the difference between a Boston and a Philadelphia chair? Well, as far as I’m concerned, the lesson is that there’s more than one good way to make a chair.

Image: Object No. 1960.0719.002. Walnut side chair with compass seat with brown leather slipseat, cabriole front legs, and ball and claw feet, Boston Massachusetts, 1740-1765. This picture shows the way in which the front legs of this chair extend up to become part of the seat rail. Photo courtesy of the Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden.

Image: Object No. 1960.1034.001 Walnut side chair with compass seat, red damask slipseat, and cabriole front legs with ball and claw feet, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1745-1755. On this seat, the wood of the seat rail is not disrupted by the front legs. Photo courtesy of the Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden.

In the middle of the eighteenth-century, many stylish chairs made in both Boston and Philadelphia had rounded compass (or “balloon”) seats, with cabriole front legs, elegantly shaped back splats, and carved crest rails. These elements, however, were put together very differently. For example, in Boston, the front and side seat rails (the pieces of the chair which support the slipseat) are fitted into the front chair legs with mortice and tenon joints. Visually, the tops of the chair legs are part of the seat rail. In Philadelphia, on the other hand, the pieces of the seat rail are assembled first and a mortise is drilled for a tenon carved into the top of the leg. From a distance, chairs from these two cities looks alike, but the way these two groups of craftsmen reached that appearance is quite different.

Image: Detail of seat rail from above, without slipseat, from a Boston side chair, 1740-1765. In this image it is possible to see how the front and side seat rail pieces fit together with the front legs. Photo courtesy of the Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden.

Image: Detail of seat rail, with slipseat pulled back from a Philadelphia side chair, 1745-1755. On the right-hand side of this image it is possible to see the front and side seat rails held together with two small wooden pins. Beside the pins the round chair leg tenon, which fits up through a mortice in the seat rail, is also visible. Photo courtesy of the Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden.

As connoisseurs, this information helps us to differentiate between the products of two of North America’s most important eighteenth-century cities. This might help us to know where a chair without a clear provenance was made, or to more accurately furnish a museum room in Philadelphia or Boston. These are ways to use our knowledge of regional characteristics to “read” an object, but we can also use the object to study the world in which it was made – now that we’ve “learned to read” we can “read to learn”.

With an interest in the history of technology, and a background as a maker, the stories I’m excited to learn are often those about how artisans construct the objects they produce. Looking at construction techniques from two different North American cities is a way not just to differentiate between objects, but to think about patterns of craft-knowledge transmission, or perhaps even more fundamentally, to consider the multiple engineering solution to the problem of stable, comfortable, and stylish seating. Given that chairs from both these cities survive today and are still admired for their appearance (though I’m afraid I’m not permitted to test their comfort), I think we can safely say that there’s more than one good way to make a chair.

By: Eliza West, WPAMC Class of 2019

Very cool, thanks for documenting that was nice photos !