Music in the Home: Parlor Soundscapes in the early 20th century

According to a late Victorian article in women’s periodical Godey’s Lady’s Book, a “parlor without a piano seems like a greeting without a smile.” This sentiment had a widespread manifestation in the social rooms of middle class America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as mechanized production of these traditionally genteel and ladylike instruments made them increasingly affordable. The merits of the piano had been commended for over a century, ultimately becoming synonymous with Victorian morality due to the rigorous and dedicated practice required. As interactive and recreational objects, keyboard instruments fit well within the atmosphere of a parlor, supporting the emphasis on sociability in the parlor’s function and interior decoration. Critical to the instrument itself, sheet music brought the piano alive and created soundscapes, an intangible yet crucial element to any interior space.

Room Interior with Piano, ca. 1911 or later. Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera Coll. 182.

Featuring a piano, the photograph above provides an excellent case study of gendered control and the curated soundscape of an interior (Figure 1). This room displays common elements of a parlor, identified by the upright William Knabe & Co. piano, concentric seating and an abundance of illumination with large windows and a variety of light fixtures; all features that contribute to the human interaction meant to occur within the space. While interior decorating of the parlor often fell under the jurisdiction of the female, there was a plethora of guidance published in periodicals and advice books to assist in their efforts. The Delineator, another popular publication in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, describes the perfect placement of the upright piano against the wall as to “not obscure the player.” It also emphasizes the comfort of the audience and room function, recommending that the “chairs should be well built and of various shapes and sizes,” and that “tables should be distributed wherever they can be of service for holding books and music,” sentiments supported by the arrangement of the parlor above.

No parlor would be complete without music to play on the piano. Sheet music occupies a liminal space between the material and immaterial, creating an intangible product when the object is in use. Additionally, the ability to select sheet music allowed the individual to personally curate the soundscape of the interior and add decoration with the colorful covers of the music. Considering historic soundscapes created by objects such as sheet music provides an often forgotten outlook into the experience of a particular space, building on the other objects within. Using the parlor photograph seen above, specific elements of the room’s soundscape can be determined. A closer look at the piano against the parlor wall exhibits a variety of rags, including Irving Berlin’s “That Mysterious Rag” (Fig. 2), revealing a jovial and spritely soundscape.

Sheet Music. Irving Berlin and Ted Snyder, That Mysterious Rag, 1911. Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera

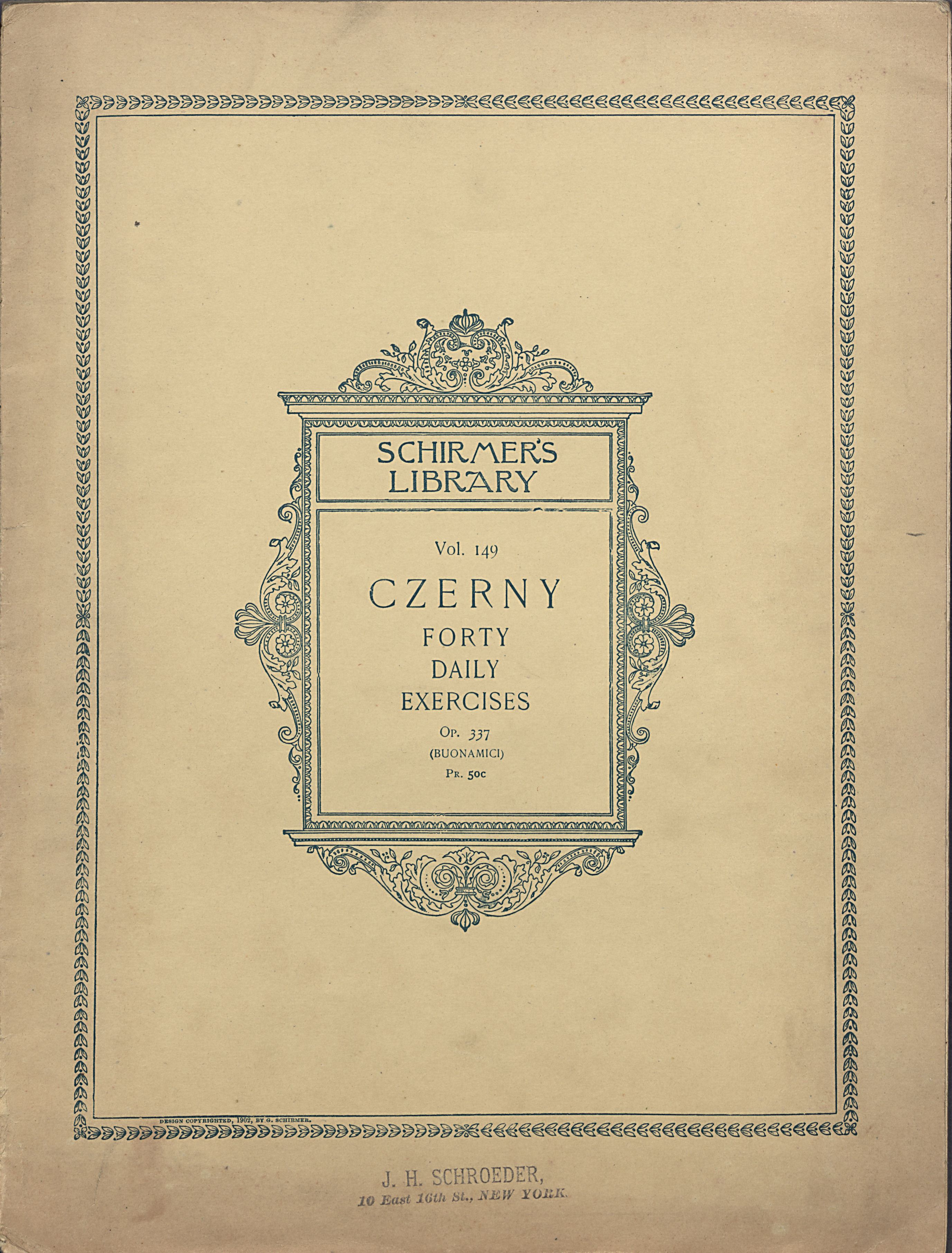

However, this particular room is also a transformative space, evident by the curtains that obscure the view of the bedroom. This transformation can be realized in both the material and the music as the room makes a transition from a private space to a social scene. While keeping the bedroom curtains open in the private environment, the occupant may turn to practicing technical etudes, such as Czerny’s Forty Daily Studies (Fig. 3), to build skill on the piano and improve performances. When the room transforms into a social atmosphere, the hostess may close off the bedroom to bring the parlor alive with company, entertaining guests around the piano with a rendition of That Mysterious Rag. With this additional aural perspective, the understanding of the parlor deepens and reveals a fuller breadth of the room’s functional versatility.

Carl Czerny, Etude Book, Forty Daily Exercises, Op. 337. First edition published in 1834, Buonamici edition published in 1897. Winterthur Library, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera

.

By Alexandra Cade, WPAMC Class of 2018

.

This post is part of a series written in the fall of 2016 for a Historic Interiors class at Winterthur. Students explored photographs housed in the miscellaneous photograph collection (Collection 182) in the Winterthur Library’s Joseph Downs Collection. These scenes each reveal a treasure trove of objects that invite further examination, speculation, and connections to other Winterthur collections.

.

Further Reading:

Bonin, Jean M. American Life in our Piano Benches: the Art of Sheet Music. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison Press, Elvehiem Museum of Art, 1985.

Dolge, Alfred. Pianos and their Makers: A Comprehensive History of the Development of the Piano. New York: Dover Publications, 1972.

Loesser, Arthur. Men, Women and Pianos: A Social History. New York: Dover Publications, 1954.

Roell, Craig H. The Piano in America, 1890-1940. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1854. See Chapter Four: Sounds.

Leave a Reply