The View from Above: Perspectives in Material Culture

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog – Caspar David Friedrich, 1818.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog – Caspar David Friedrich, 1818.

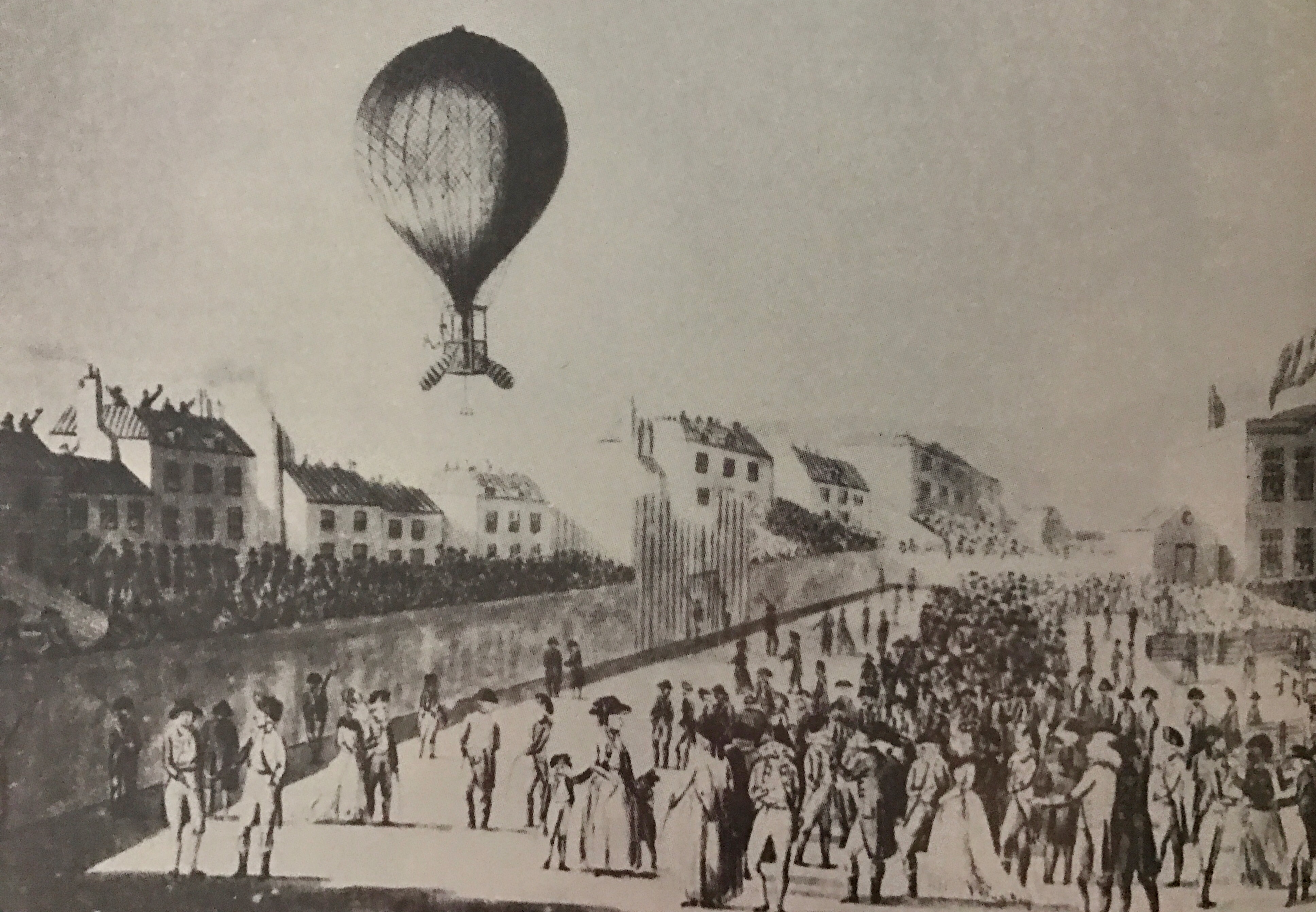

On September 15th 1784, a great red and white striped balloon arose from Moorfields, artillery grounds just outside of London. In the balloon basket stood Vincent Lunardi, a recent Italian émigré to London, peering down at the jubilant crowds below. This was the first human flight in England, coming only months after the advent of balloon flight in France. Equipped with oars, Lunardi proceeded to “steer” the hydrogen-filled balloon for thirteen miles and successfully land it in a cornfield a few hours later. “I saw the streets as lines,” Lunardi recorded in his Account of the First Aerial Voyage in England, “all animated with beings, whom I knew to be men and women, but which I should otherwise have had a difficulty in describing. It was an enormous beehive, but the industry was suspended…[the] admiration and glory of the present moment, was not without its effect on my mind.”

Vincenzo Lunardi’s balloon ascending from Artillery Ground, City Road, Finsbury, London, 1784. Engraving by Francis Jukes.

From his account, it is clear that Vincent Lunardi was appreciating his newfound perspective. The joy was twofold: the audience on the ground was enthralled by the prospect of man sailing the skies, effortlessly floating upwards in a brightly colored mass of silk. Many even believed it would become the new standard for transportation. But for those who were able to ride in the balloon itself, a unique and unparalleled view of the landscape was presented. The mundane, every-day terrain seen at eye-level became extraordinary and sublime when seen from a few hundred feet in the air. The bustling streets of London turned into a clear-cut map, intersected by the curve of the Thames. Neighborhoods, separated on the ground by social class and architecture, blurred together as part of a larger picture. The urban shackles of the city faded away as the hilly farmland of Surrey appeared in the distance.

It is this phenomenon, the search for a new perspective, which we found ourselves chasing in England. Most times, we found it on the ground –hearing from a learned curator, experiencing an innovative exhibit, or seeing the juxtaposition of the old and new in the ever-evolving streets of downtown London. But sometimes we were rewarded with that extraordinary view that only comes with seeing something from above. If there was something to climb, something to provide us with that unique perspective, we climbed it. Sure, it took a lot of (sometimes precarious) steps to get there without Vincent Lunardi to whisk us away in his silken balloon.

Left, the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral as seen from the ground. Right, view of the Thames from the top of St. Paul’s Cathedral, known as the “Golden Gallery.”

Walking around the top tier of St. Paul’s Cathedral, 528 steps in the air, the oldest part of London appeared before me: the layout and street plan. While we certainly weren’t as high up as Mr. Lunardi’s balloon, we were able to get a glimpse of the “enormous beehive” that he described in his account. Height had bestowed upon us a manageable vision of the dynamic city below, allowing us to discern contrast between buildings in the infancy of construction and structures centuries old, all in one line of sight.

The search for the sublime didn’t stop in London – I found it in Paris on my day off. Left and Right, views of the Seine as seen from the top of Notre-Dame. Center, Notre-Dame de Paris as seen from the ground.

Since many of the cities we toured developed on rivers, it was often possible to perceive the evolving relationship between humans and the natural environment. Standing over the River Severn on the famous “Iron Bridge” in the aptly named former-factory town of Ironbridge, we could see how nature was reclaiming what had been lost at the height of industrialization.

Left, WPAMC 2018 perched upon the Ironbridge in Telford. Right, the idyllic view from the bridge.

Each of these vistas evoked the Romantic notions of the sublime; I had “mastery” over the landscape in viewing it from above, yet I was just one individual in a beehive of millions. I was standing over a great precipice, sometimes hundreds of feet above the ground, but I was safe, protected by guardrails and barriers.

Left, Beckford’s Tower in Bath as seen from the ground. Right, view of the countryside from the top of Beckford’s Tower.

Left, Beckford’s Tower in Bath as seen from the ground. Right, view of the countryside from the top of Beckford’s Tower.

Left, Folly at Goldney Hall as seen from the ground. Right, view of Bristol from the top of the folly.

Left, Folly at Goldney Hall as seen from the ground. Right, view of Bristol from the top of the folly.

More importantly, the various panoramas provided a perspective of material culture on a large scale. As scholars of objects, we spend so much time studying details, but placing them in context of the intentionally modified environment is just as crucial. Just as Lunardi delighted in revelations gained from viewing London from above, our class gained new perspectives that will serve us well as we pursue our studies in material culture.

By Allie Cade, WPAMC Class of 2018

Beautifully written and sensitively expressed. I found myself a passenger in both Mr. Lunardi’s balloon and in Ms Cade’s artful voyage. Thank you for the pleasure!

Beautifully written and sensitivemy expressed. I found myself a passenger in both Mr Lunardi’s balloon and I. Ms Case’s artful voyage. Thank you for the pleasure!