The Ephemera of Halloween

Every year, we bring out the cobwebs, carve the pumpkins and ready that doorside bowl of candy in honor of All Hallow’s Eve. Months in advance, stores stock their shelves with Halloween ephemera – the latest décor of ghosts, goblins and pumpkins. Children (and adults) prepare their costumes, looking for something just a little scarier, or a little wittier, than the year before. Halloween in 2016 is an incredibly commercialized experience – but not much more so than Halloween in 1916.

So how did America celebrate Halloween 100 years ago?

In the early 20th century, the season was observed with similar festivities. Just as today, people liked to dress up in costume, and they liked to throw parties.

Dennison’s Bogie Book, 1915. Image courtesy of Amazon. Dennison’s Bogie Book began publication in 1909, producing a new edition every year.

A new market of seasonal ephemera catered to this burgeoning industry, especially towards the grand Halloween gatherings that flourished each fall. Celebrations in the United States were more of an adult activity, often occurring in the form of a party. Products were created specifically for the occasion of a Halloween soiree – everything from invitations and house décor to party games and food items. If a host was looking for guidance on throwing the autumnal event of the season, Halloween “Bogie Books” were sold, boasting advice and suggestions for proper decorating and entertaining at these wild parties.

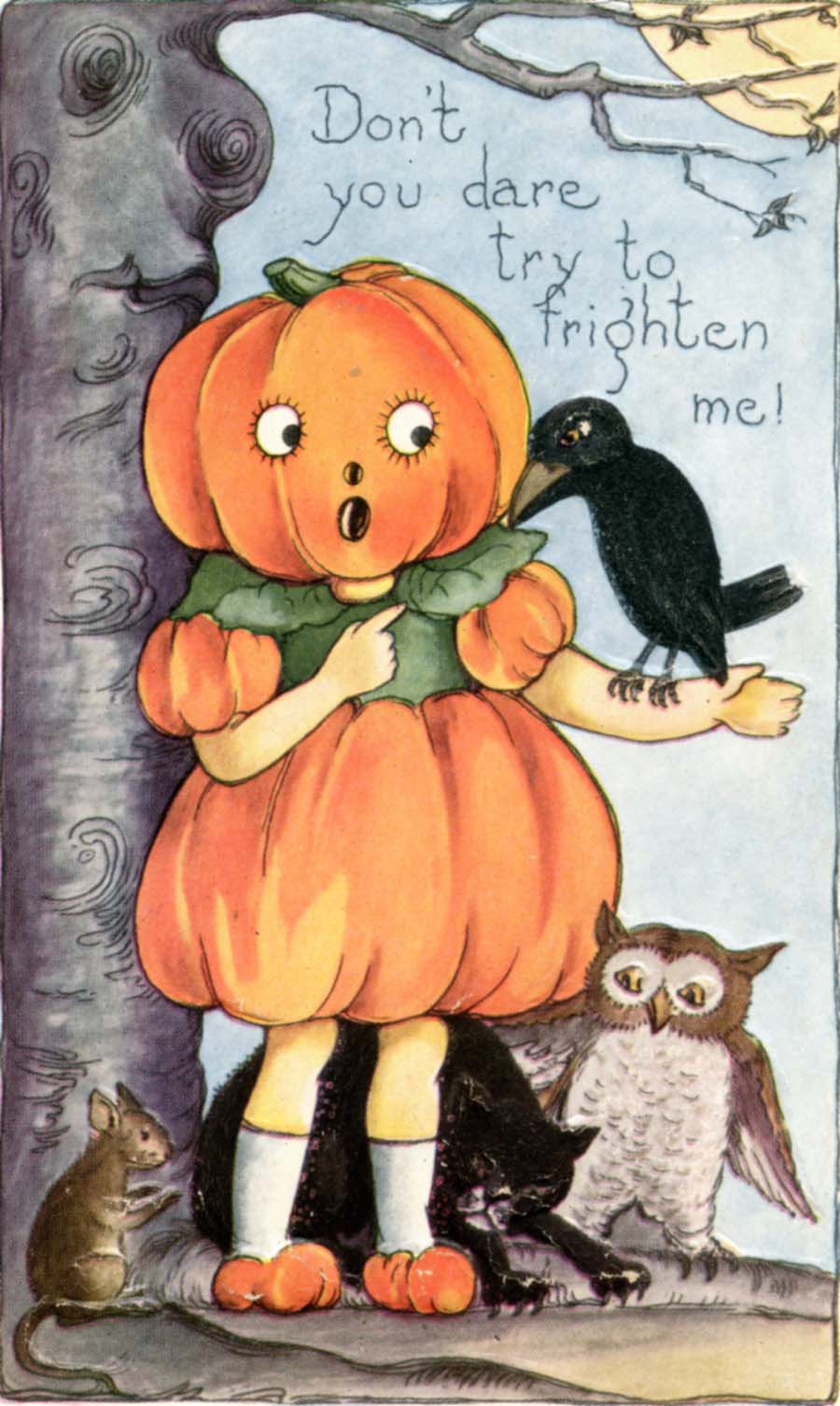

Greeting card, early 20th century. George C. Whitney Company. The little girl, dressed as a pumpkin, is surrounded by wilds of the night – a mouse, black cat, owl and raven.

Sending out seasonal greeting cards was a popular gesture. The greeting card industry boomed in the early 20th century, with beautifully illustrated options for major holidays like Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Halloween, Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July. Halloween cards often featured cute children, witty messages or conventional Halloween figures – pumpkins, witches and ghosts.

Greeting card, 1918. George C. Whitney Company. For some, perhaps the “thinning of the veil” between life and death spurred boldness to proclaim Romantic feelings.

Greeting card, early 20th century. “A busy Jack Lantern.” A mischievous lad is making good use of his pumpkin – scaring wayward travellers with the carved gourd.

Halloween party invitation, early 20th century. Image courtesy of the author.

Greeting card, 1917. A cherubic little girl stands with a black cat, holding a friendly jack o’lantern proclaiming “A Merry Halloween”

Greeting card, 1912.

Greeting card, early 20th century. “What the Pig tho’t of the Ghost.” A large pig has consumed the “ghost” that the prankster prepared, with a witch overlooking the scene atop the moon.

Once the seasonal greeting cards and invitations for a Halloween party had been sent out, it was time to prepare for the upcoming festivities. Stores stocked a plethora of decorations to choose from, including cardboard cutouts, wall and door hangings and tablecloths.

Cardboard cutout of grinning Jack O’Lantern, Beistle Company.

Cardboard cutout of witch riding over the moon.

Cardboard door or wall hangings of an anthropomorphic black cat couple, dressed in seasonally festive clothing.

Crepe paper tablecloth featuring pumpkins and cats. I can’t promise that the red stains aren’t blood.

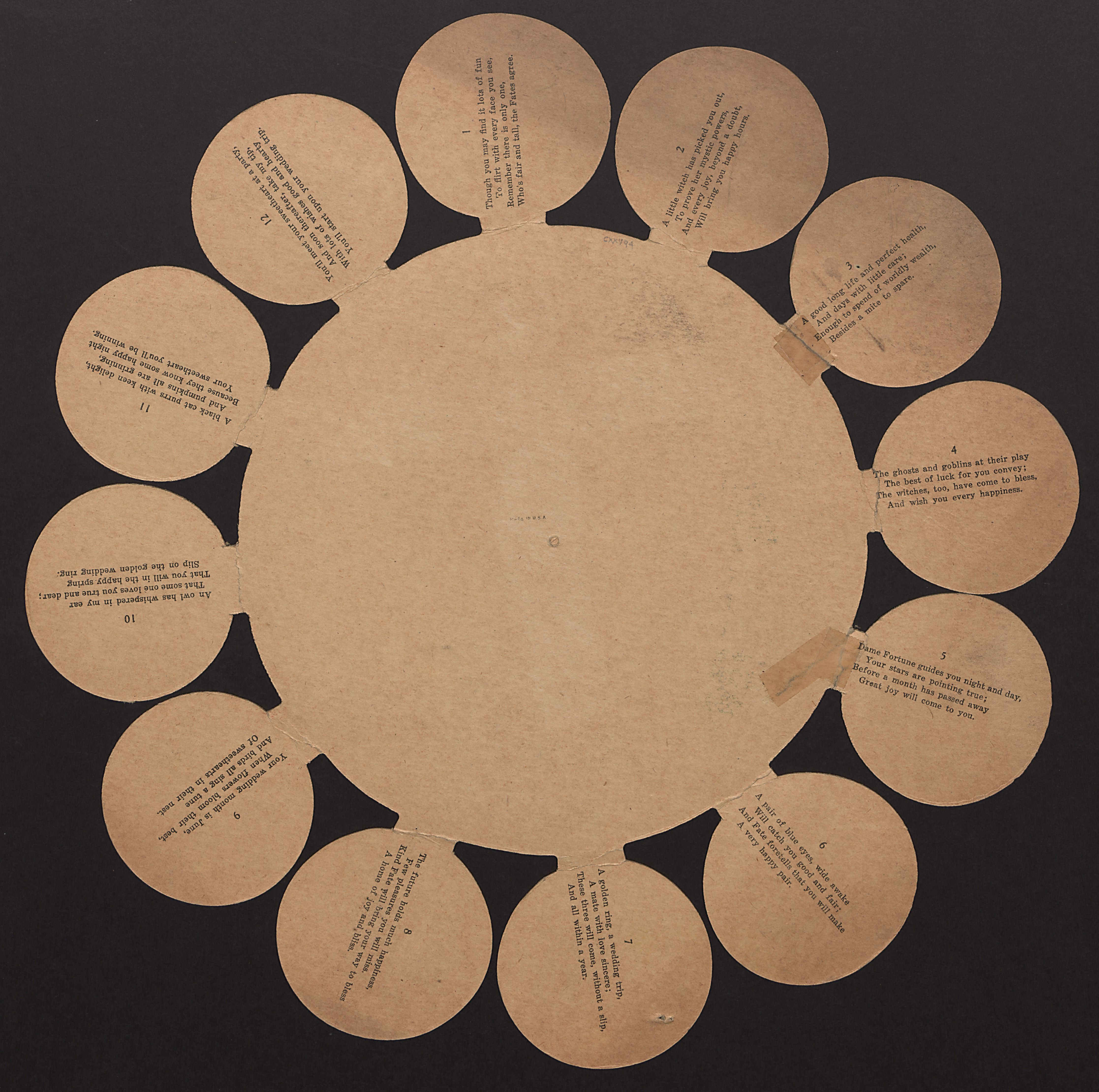

When the evening of the party arrived, it was necessary to have plenty of activities on hand. Bobbing for apples, reading fortunes, performing stunts and playing games were popular pastimes at these events. A trendy game was entitled “Pick a Pumpkin,” which fused fortune-telling and Halloween spirit. Though it could be played in a variety of ways, the premise of the game required the players to select a pumpkin from the lot, which held their future on the reverse side.

Pick a Pumpkin, front and back

The game could be played with a cutout disc nailed to a wall, spun around, and each pumpkin ripped off. “Pick a Pumpkin” was also sold in the form of a fishing game, where the pumpkins were set up in small metal holders with magnets attached to their stems. The players would then use a small “fishing rod” with a magnet on the end to select a pumpkin and receive their fortune.

Halloween provided the perfect backdrop for flirtation, as the veil between the living and dead was thinned – the air was charged with an extra dose of risk. The dark came alive, and what was typically obscured in the daytime could be revealed. What better time to confess romantic affection? Fortune-telling games at these parties capitalized on this feeling, some of the messages in “Pick a Pumpkin” included:

“An owl has whispered in my ear

That some one loves you true and dear;

That you will in the happy spring

Slip on the golden wedding ring.”

“You’ll meet your sweetheart at a party,

And soon thereafter, take my tip,

With lots of wishes good and hearty

You’ll start upon your wedding trip.”

“A golden ring, a wedding trip,

A mat with love sincere;

These three will come, without a slip,

And all within a year.”

When the seasonal jubilee had ended, it was time to commemorate the experience. Salvageable mementos such as invitations, pictures and fortunes from parties could be placed onto pages for scrapbooking, a fashionable hobby of the time. To embellish a page of such keepsakes, small paper cutouts, or “scraps,” could be glued in. Scraps were die-cut and sold in sheets, printed in a range of seasons and subjects. They were especially versatile pieces of ephemera, as scraps could be added as adornment on a huge variety of things.

Littauer and Boysen Pumpkin scraps, printed in Germany.

When All Hallow’s Eve comes around this year, consider where your traditions came from. Our modern concept of Halloween, beginning in the early 20th century, has ancient roots in a variety of cultures. What better way to celebrate than to revive some 100 year-old traditions and play an old-fashioned game of “Pick a Pumpkin?”

Have a Happy Halloween, and keep an eye out for those mischievous Jack O’Lanterns!

Image courtesy of Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images.

.

By Allie Cade, WPAMC Class of 2018

All images, unless otherwise marked, are courtesy of the Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera at the Winterthur Museum.

Brilliantly written article! Bravo!