Day 10 in England- All that Glitters is Gold

On Wednesday the 27th, we left our hotel bright and early and headed over toward St. Paul’s Cathedral which was very close to our first stop of the day: Goldsmith’s Hall. The headquarters of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and the location of the London Assay Office, this enormous building takes up nearly an entire city block! The current building was built in the early 19th century and was damaged during World War II when a bomb exploded in the southwest corner. Luckily, however, the majority of the building survived, the damaged restored, and we were able to see many of Philip Hardwick’s amazing interiors. Unfortunately photography is not allowed in Goldsmith’s Hall so I am forced to rely on images found online (luckily the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths has a great Facebook page, “The Goldsmith’s Company,” where I found many of these images).

At the Goldsmith’s Company we were greeted by David Beasley, the Librarian who gave us a brief tour of the building before showing us some of the library’s treasures.

The Grand Staircase as you go into Goldsmith’s Hall is truly an impressive sight. According to Mr. Beasley, Hardwick had originally intended for this space to be paneled with wood, but after his death, the architect who finished the building decided that marble would be a better choice. World War II bombing damaged several of the marble elements beyond repair and they were replaced in kind, and some of this infill is visible if you really scrutinize things.

The Drawing Room. This room, and several others at Goldsmiths’ Hall, has found its way to stardom having been the site for several major fashion shows and used as a setting in shows like Sherlock, Britain’s Got Talent, and a Winterthur favorite: Downton Abbey. It is perhaps ironic, then, that this room was heavily damaged during World War II, meaning much of what you see is part of the post-War reconstruction.

Perhaps the most impressive room is the Livery Hall, which is used for official functions of the Goldsmiths’ Company. Truly an impressive space, there’s no reason to try and describe it with words because it’s impossible. I would strongly suggest copying this link and visiting the space for yourself. It’s not as good as being there in person, but it gives a pretty good idea of how beautiful the room is! http://pan3sixty.co.uk/virtual_tours/goldsmiths-company/livery-hall

Following our tour of the building the group split up and half us stayed to look at some library treasures while the other half went with Dave Merry, the Head of Training, Education & Trading Standards Liaison, to go learn about the Assay Office.

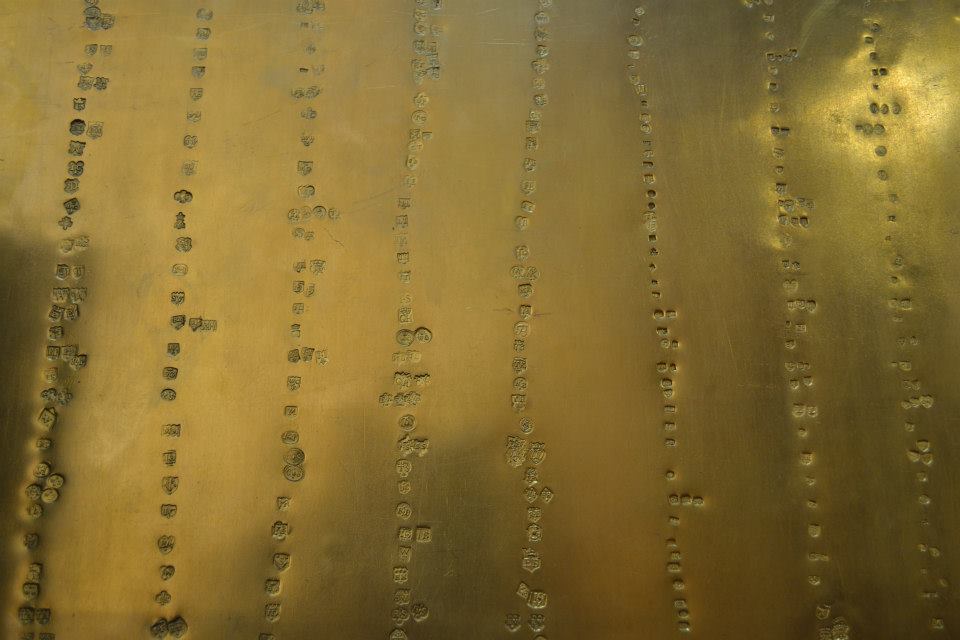

With David Beasley we looked at many items related to the history of fine metalworking in London and to the Goldsmiths’ Company itself, which received its royal charter in 1327. We saw books, ledgers, and a really interesting plate dating to the 17th century upon which members of the company would strike their mark. (The plate we saw was actually an electrotyped copy, but it was still really cool.)

Following our library session the groups switched and we went down into the Assay Office with Dave Merry, where precious metals go to be hallmarked, certifying they are of the proper quality and are truly what they claim to be. Here 16,000(!) items are hallmarked daily, some by hand, some by laser engraver, but all are verified to be exactly the quality they claim to be. In some instances touch stones are used while in other cases XRF Spectroscopy is used to verify the quality of the metals. It’s all highly technical science that went way over my head, but it was really interesting seeing it done and Dave did a great job trying to make the process seem accessible and understandable, even to a group of non-science people!

Following our library session the groups switched and we went down into the Assay Office with Dave Merry, where precious metals go to be hallmarked, certifying they are of the proper quality and are truly what they claim to be. Here 16,000(!) items are hallmarked daily, some by hand, some by laser engraver, but all are verified to be exactly the quality they claim to be. In some instances touch stones are used while in other cases XRF Spectroscopy is used to verify the quality of the metals. It’s all highly technical science that went way over my head, but it was really interesting seeing it done and Dave did a great job trying to make the process seem accessible and understandable, even to a group of non-science people!

In the afternoon we made our way to Greenwich, where we covered an amazing amount of ground in a very short time (a common theme during our England trip). Starting at the visitor’s center, some members of our group took advantage of the opportunity to try on some costumes and I think you’ll agree that these are styles that really ought to be introduced to America.

In the afternoon we made our way to Greenwich, where we covered an amazing amount of ground in a very short time (a common theme during our England trip). Starting at the visitor’s center, some members of our group took advantage of the opportunity to try on some costumes and I think you’ll agree that these are styles that really ought to be introduced to America.

Leaving the costumes (and Visitor’s Center) behind, we walked among the buildings formerly occupied by the Royal Naval College and discussed the architecture of the buildings, which were designed and executed at the end of the 17th century by the architectural powerhouse of Sir Christopher Wren and Nicholas Hawksmoor.

With daylight rapidly coming to a close, we rushed to the Queen’s House (designed by Inigo Jones and built between 1619 and 1635). The Queen’s House is one of those buildings that, at least for me, no matter how many times I see it, I still get excited. Bright white, it stands out from its surroundings and, though small, it has a wonderful presence about it.

We took a bit of time to explore the interior of the building, with its wonderful 40’x40’x40’ (a perfect cube) salon. In many of the rooms magnificent paintings were on display, covering over four centuries of history, many originating from the Royal Naval collection.

The Tulip Stairs in the Queen’s House are supposedly the first centrally unsupported helical stairs in England. They are also among the most photogenic stairs I’ve ever encountered.

The Tulip Stairs in the Queen’s House are supposedly the first centrally unsupported helical stairs in England. They are also among the most photogenic stairs I’ve ever encountered.

Leaving the Queen’s House we mustered the strength (it was a struggle for some of us) to climb the hill so we could could visit the Royal Observatory. We were rewarded at the top by wonderful views of the Queen’s House, the Royal Naval College, and London.

Of course, while we were there we had to go visit the the Prime Meridian and take the requisite photographs before heading into the Observatory itself. Officially called Flamsteed House, this building was designed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1675 on orders from Charles II.

The red ball is called a time ball and was used to help synchronize the time each day. At 1pm daily the ball would drop and people could then synchronize their clocks. Something tells me that watching the ball drop in 1675 was not the same as watching the ball drop in New York City on New Year’s Eve…

After touring the Royal Observatory and its exhibits (many of which were unfortunately deinstalled as the galleries are being updated), we raced back down the hill. To get the most out of Greenwich, we stopped in at the National Maritime Museum to see the wonderfully ornate Royal Barge designed by William Kent and built for Frederick, Prince of Wales, in 1731-32.

Last used to to carry Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to the opening of the Coal Exchange, it now sits in a place of honour in the National Maritime Museum. The detail in the carving is really impressive and I was particularly amused by the somewhat mythically rendered sea lions. As one member of our group pointed out, they sort of look like dogs hanging out of a car window. I quite agree.

Last used to to carry Queen Victoria and Prince Albert to the opening of the Coal Exchange, it now sits in a place of honour in the National Maritime Museum. The detail in the carving is really impressive and I was particularly amused by the somewhat mythically rendered sea lions. As one member of our group pointed out, they sort of look like dogs hanging out of a car window. I quite agree.

After our visit to the Barge we rushed to the Chapel of the Royal Naval Hospital which was designed by Sir Christopher Wren but completely redecorated by James Stuart following a terrible fire in 1779. It is just breathtaking!

With the day quickly coming to an end, we ran (literally) across the courtyard to see the Painted Hall, and were able to enjoy it for a few minutes before it closed. Originally used as a dining hall for the naval officers living at the hospital, its decorations were painted by Sir James Thornhill and reference British naval strength. Unfortunately I was a bit too smitten with the paintings to really focus on good photos, but here’s one that gives just a tiny idea of how the ENTIRE space is decorated.

With the Painted Hall closing we made our way back to London and the group broke apart depending on what individuals wanted to do with their evening.

With the Painted Hall closing we made our way back to London and the group broke apart depending on what individuals wanted to do with their evening.

Willie Granston, Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, Class of 2016