Professional Identity: Tradespeople as Composite Figures in European Prints

Funnels, lanterns, pitchers, and cake molds number among the wares that form the theatrical costume of Martin Engelbrecht’s Tinsmith, one of 170 engravings from his series Artists, Craftsmen, and Professionals (circa 1730). In them, Engelbrecht continued a pictorial tradition of composite figures that dates back at least to the late sixteenth-century painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Composite figures, which depict people as assemblages of objects related to their occupation, remained popular into the 1900s. Artists achieve diverse results using this representational device, but their images consistently suggest that professions define the individual.

![Martin Engelbrecht, Un Cofretier/Ein Flaschner [Tinsmith], German, ca. 1730, Hand-colored Engraving on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1955.135.5, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.](https://sites.udel.edu/materialmatters/files/2015/01/Engelbrecht-Tinmaker-1kznrfe-e1420496324130.png) Martin Engelbrecht, “Un Cofretier/Ein Flaschner [Tinsmith],” German, ca. 1700-1756, Hand-colored Engraving on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1955.135.5, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Martin Engelbrecht, “Un Cofretier/Ein Flaschner [Tinsmith],” German, ca. 1700-1756, Hand-colored Engraving on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1955.135.5, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Engelbrecht, a leading producer of expensive ornamental prints and paper theaters in Germany, created this engraving to entertain elites, an audience indifferent to mechanical instruction and accuracy. The Tinsmith shows us the products of his trade, but nothing of his business or skills. The text at the bottom of the page is a key to the numbered objects, which provides information mostly pertinent to an audience of discriminating consumers. Identifying the laborer through appealing and uncontroversial material associations, Engelbrecht uses the composite figure to skirt unpleasant, practical realities. James Goodwyn Clonney’s painting of a humble “tin man” repairing a leaky kettle is more consistent with the routines documented in tinsmiths’ account books than Engelbrecht’s exuberant engraving.

James Goodwyn Clonney, “The Tinsmith,” North American, 1832-1867, Oil on Canvas, Winterthur Museum, 2003.12.25 A, B, Bequest of Mrs. Helen Shumway Mayer

James Goodwyn Clonney, “The Tinsmith,” North American, 1832-1867, Oil on Canvas, Winterthur Museum, 2003.12.25 A, B, Bequest of Mrs. Helen Shumway Mayer

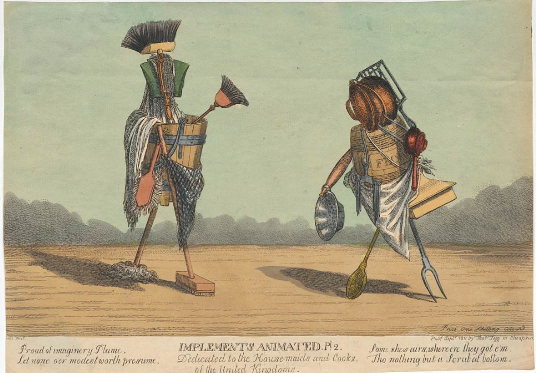

English satirist Charles Williams also used composite figures in Implements Animated of 1811, but to different effect. Consisting of objects alone, his Housemaid and Cook fully inhabit their professional identities. Although fantastic and strange, Williams in fact depicts occupations more faithfully than Engelbrecht. The implements used to create these portraits demonstrate Williams’ nuanced, informed understanding of the specific duties required of Housemaids and Cooks in Regency England.

Charles Williams (Etcher) and Thomas Tegg (Publisher), “Implements Animated, Plate 2,” English, 1811, Hand-colored Etching on Wove Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1967.201, Museum Purchase

Charles Williams (Etcher) and Thomas Tegg (Publisher), “Implements Animated, Plate 2,” English, 1811, Hand-colored Etching on Wove Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1967.201, Museum Purchase

Unlike Engelbrecht, Williams offers critical commentary on his subjects. Captions beneath each figure allude to vanity and pride in English domestic servants. “Proud of imaginary Plume, Let none our modest worth presume,” says the maid. “Some shew airs where ere they got ’em Tho nothing but a Scrub at bottom,” cook retorts. Together with the text, Williams employs the tools identified with Housemaids and Cooks to ridicule their pretension. Printed toward the end of the golden age of British satire, Williams’ Implements Animated applies the composite figure to a visual culture concerned with disruptions in social hierarchy and self-invention through fashion. For Williams, the tools that surround people daily are the truest measure of identity and status.

Tabart & Co., “Tin-Plate Worker,” from “The Book of Trades,” London: B. & R. Crosby, 1804-1805, T47 B72 S, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Tabart & Co., “Tin-Plate Worker,” from “The Book of Trades,” London: B. & R. Crosby, 1804-1805, T47 B72 S, Printed Book and Periodical Collection, Winterthur Library

Composite figures reveal material culture to be an important function of identity. Late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century guidebooks include desirable personality traits and the social distinction of trades alongside summaries of the training, wages, skills, and responsibilities specific to them. The London Tradesman (1747) and The Book of Trades (1804-1805) addressed parents considering their sons’ professional options. Manuals like Samuel and Sarah Adams’ The Complete Servant (1825) summarized the proper comportment and duties of domestic servants for the benefit of those in such positions as well as those who employed a household staff.

A desire to understand both one’s prospects and fitness for particular jobs persists today. Career aptitude tests allow people to find professions that complement both their abilities and personality, advancing the belief that one’s labor is inseparable from his or her identity. Using the professions illustrated by Engelbrecht and Williams in the Winterthur Collection of Maps and Prints, the career aptitude quiz above invites you to place yourself in the pre-industrial labor market.

Objects and images shown in the quiz represent the collections of the Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library. Many of these can be explored further through the museum’s online database.

Key to Quiz Objects & Images

Question One: Pick a Tool

Toasting Rack, North American, 1750-1800, Wrought Iron, Winterthur Museum, 1960.919, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Box with Measuring Tape, North American, 1790-1810, Paper and Linen, Winterthur Museum, 1954.12.1, Museum Purchase

Hearth Brush, North American, 1800-1835, Wood, Bristles, Winterthur Museum, 1959.1146 A, B, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Hammer, English, 1750-1800, Wood, Oak, Iron, and Steel, Winterthur Museum, 1957.26.378 A, B, Museum Purchase with Funds Provided by Henry Belin du Pont

Wood & Caldwell Factory, Sprig Mold, English, 1790-1818, Plaster, Winterthur Museum, 1954.77.27, Gift of Arthur J. Sussel

Comb, North American, 1700-1800, Walnut, Winterthur Museum, 1952.274, Gift of Henry Francis du Pont

Question Two: Where Do You Want to Work?

Bowles & Carver, The Young Sweep Giving Betty Her Christmas Box, English, 1770-1780, Ink on Laid Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1973.584

Charles Hunt and William Summers, Life in Philadelphia, Plate 12, English, 1829, Ink and Watercolor on Wove Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1975.8, Museum Purchase

James Goodwyn Clonney, The Tinsmith, North American, 1832-1867, Oil on Canvas, Winterthur Museum, 2003.12.25 A, B, Bequest of Mrs. Helen Shumway Mayer

Shaping and Modeling Vases and Pots, Chinese, 1810-1820, Ink and Watercolor on Paper, Winterthur Museum, 2003.47.14.5, Gift of Leo A. and Doris C. Hodroff

H. Fossette, Charles Burton, George Melksham Bourne, and J. & G. Neale, Phenix Bank, Wall Street, New York, North American, 1831, Ink on Wove Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1974.147.65

Charles Knight and Henry William Bunbury, A Barber’s Shop, English, 1773-1800, Ink on Wove Paper, Winterthur Museum, 1959.98.18, Museum Purchase

Question Five: Choose Your Material

Mold Pan and Lid, English or North American, 1750-1825, Brass, Iron, Iron Wire, and Tin, Winterthur Museum, 1965.1697 A, B, Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont

Soap Suds, Image Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Fish, Image Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

Memorial Miniature, North American, 1808, Gold, Glass, Ivory, Hair, Paint, Pearl, and Brass, Winterthur Museum, 1994.81

Coat, North American, 1760-1780, Wool, Winterthur Museum, 1958.123.1, Museum Purchase

Punch Bowl, English, 1750-1770, Tin-Glazed Earthenware, Winterthur Museum, 1956.38.76, Museum Purchase

By Amy Griffin, Winterthur Program in American Material Culture, Class of 2016