Ecology.

Adapting to these disruptions, many individuals have turned to art making to revitalize and assert their knowledge of the changing land. The Yup’ik and Inuit works in this gallery emerge from a view that integrates humans within the environment. Cultural practices acknowledge the agency of other beings and systems, while seeking to maintain positive relations. For example, animals are understood to observe human behavior and determine whether to give themselves to hunters. Similarly, Ella (Yup’ik: weather, world) and Sila (Inuit: air, breath, spirit) reference a sentient life force that animates the world and responds to human thought and deed. Qanruyutet, Yup’ik “words of wisdom,” are key to maintaining ecological balance. Avatittinnik Kamatsiarniq, an equivalent Inuit principle, promotes respect and care for the environment.

Seal and Pup

c. 1960 – 1980

Kakulu Saggiatok (Inuk, b. 1940)

Graphite on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Mother Bear with Cubs

1998

Kingwatsiaq (King) Jaw (Inuk, 1962 – 2012)

Serpentine

Museums Collections, Gift of Carol A. Heppenstall

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Jaw portrays a mother nanuq (polar bear) and her cubs walking across a smooth landmass, perhaps an ice drift or part of the Arctic ice pack. He carved Mother Bear with Cubs from a single slab of black serpentine, exemplifying how the natural shape of stone influences the composition of Inuit sculpture. While Inuit hunt nanuit for food, shelter, and tools, the animals carry additional cultural significance. Inuit oral stories commonly feature nanuit speaking and acting like humans, indicating that the relationship between Inuit and animals is fluid and without hierarchy.

A Highlight Essay by Rebeccah Swerdlow

A Highlight Essay by Zoe Weldon-Yochim

Birds Holding World, Moon

c. 1988 – 2000

Qavavau Manumie (Inuk, b. 1958)

Crayon and marker on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Birds Holding World, Moon uses scale to emphasize the relational bond between the world and the life it sustains. Conventionally pictured as a small creature, the bird on the left is larger than the Earth, while the bird on the right is comparable to the size of the Moon. The rescaling of the birds in relation to the celestial bodies suggests that even those life forms considered “small” are actually of great importance. The birds are assigned to keep the planet and moon afloat and in motion. Their authoritative position counters an anthropocentric view of the earth, which typically grants humans supremacy over other forms of life and matter. Manumie foregrounds Inuit respect for animals to reframe the iconic satellite image of the solitary whole Earth that has shaped global environmental consciousness since the 1960s.

Children and Birds

1976

Kingmeata Etidlooie (Inuk, 1915 – 1989)

Ink and graphite on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

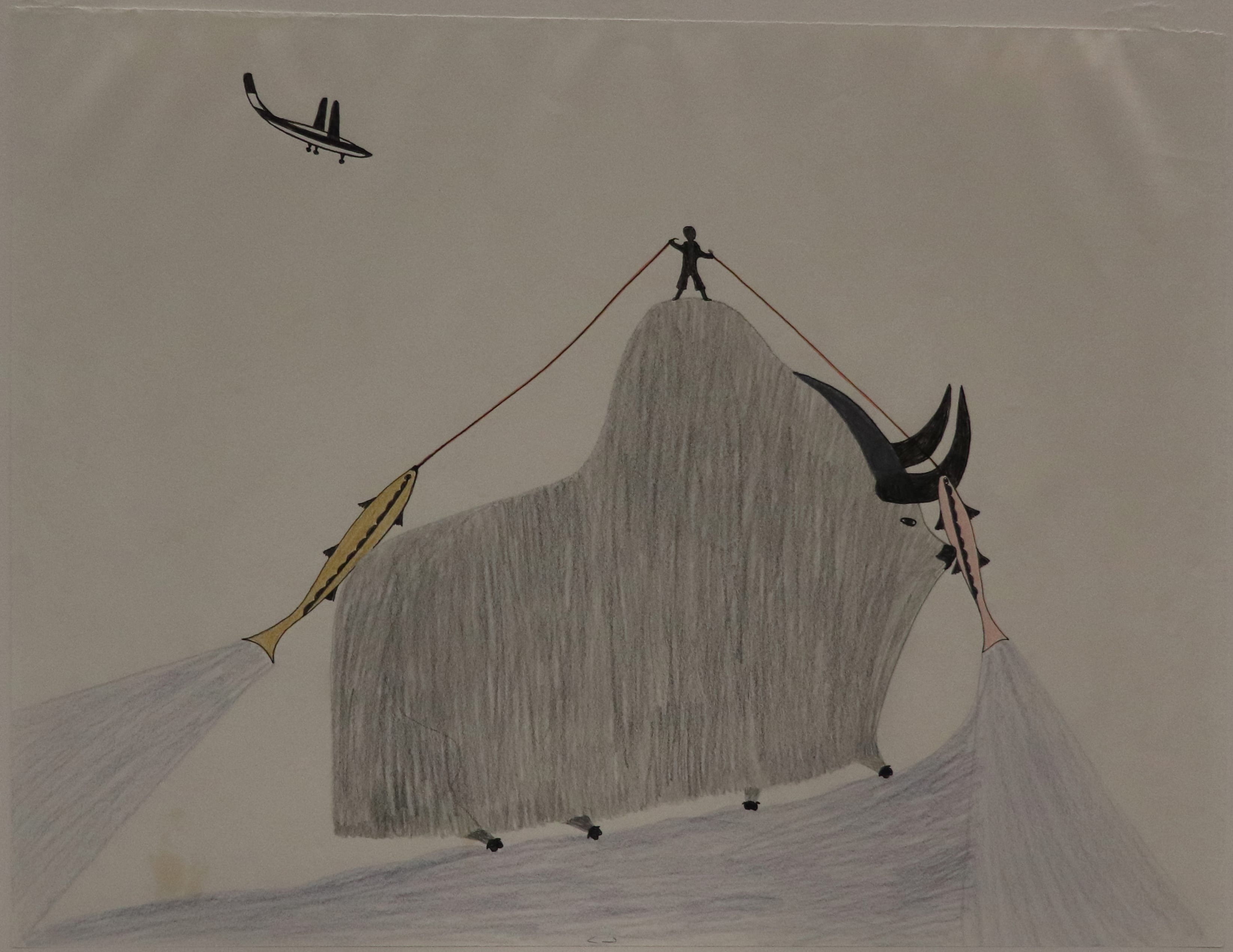

Fishing

c. 1960 – 1990

Pudlo Pudlat (Inuk, 1916 – 1992)

Crayon on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Owl, Birds, Fish

c. 1960

Kenojuak Ashevak (Inuk, 1927 – 2013)

Color pencil and felt marker on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts

Among the most famous Inuit artists of her generation, Kenojuak Ashevak was the first woman in Kinngait (Cape Dorset) to pursue art as a vocation. This balanced composition features a lone owl at the center and pairs of sea gulls, ptarmigans, and petrels on either side. The symmetrical format reflects that of sealskin appliqués, which are produced by folding the skin in half before cutting the design, resulting in identical sides.

Resting Musk Oxen

c. 1982 – 1983

Pudlo Pudlat (Inuk, 1916 – 1992)

Crayon and ink on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Frederick & Lucy S Herman

Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts