How did free Blacks use legislative petitions to protest racial oppression in antebellum Delaware?

By: Krishanna Prince | Posted: 7-7-2022

Before the Fifteenth Amendment extended voting rights to Black men, free Black Delawareans were unable to use the ballot to challenge oppressive laws or elect leaders who would advocate for their liberation.[1] However, through petitioning, Black voices enter the historical record for us to examine. Petitioning was common in antebellum America for historically oppressed groups who were denied participation in formal politics.[2] As documents, petitions transform human emotions of pain and outrage into textual grievances directed towards those in power such as legislatures and courts.[3] In Delaware, free Blacks petitioned against “…nuisance laws fashioned to support racial social control” which came to be notoriously known as “Black codes.”[4]

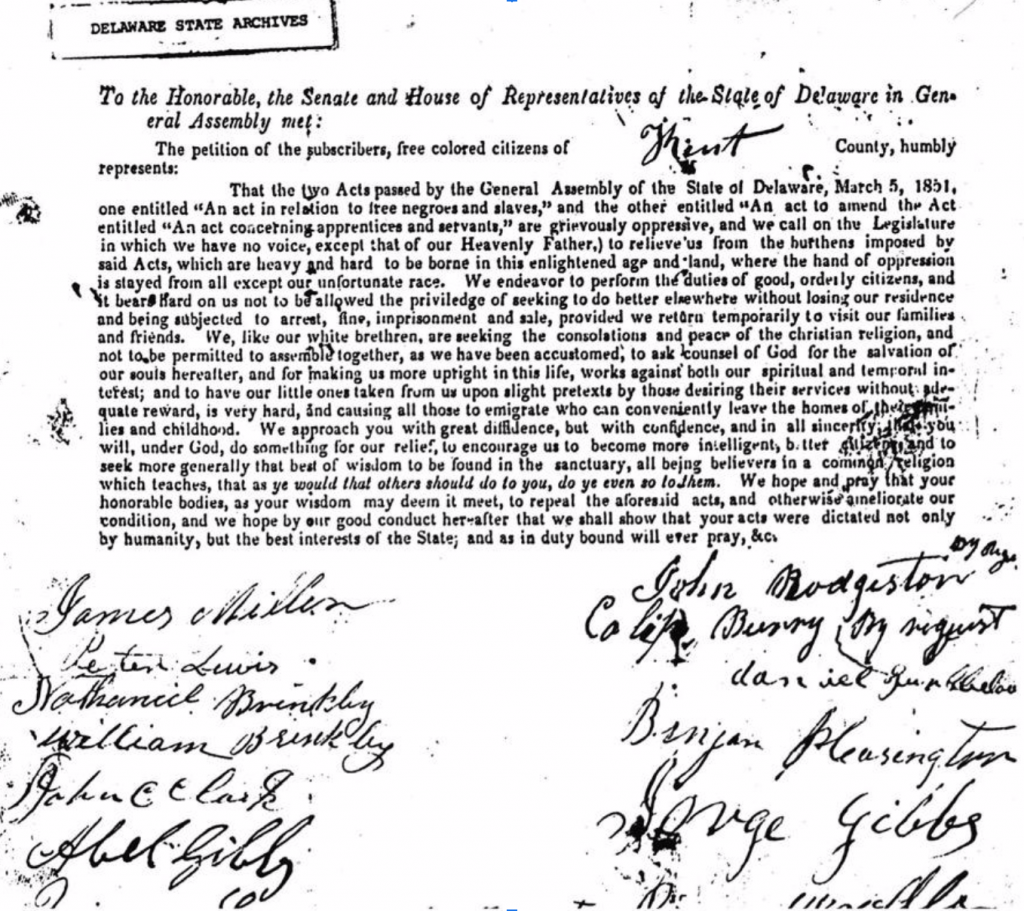

For my research, I looked to Black-authored sources by examining petitions filed by free Blacks to Delaware’s legislature between 1830 and 1869. These petitions come from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG)’s Race & Slavery Petitions Project which collected 2,975 legislative petitions and 14,512 county court petitions made by enslaved people, free people of color, and whites in slaveholding states between 1775 and 1867.[5] Collections of these petitions are physically located in two series of reels in the University of Delaware’s microform room in Morris Library.[6] This research project examines twelve legislative petitions to investigate how free Blacks in Delaware framed their grievances as racial oppression in response to four laws that comprised the “Black Codes.” The voices of free Black petitioners shed light on how they used petitions to protest such laws passed by the Delaware legislature. Legislative petitions were used by free Blacks to detail their lived experiences of Black Codes as criminalizing their activity and restricting their freedom, emphasize their good character, expose the contradictory nature of Black codes, and appeal to the interests of legislators.

Analyzing the Petitions: Arguments for Alleviation of Oppression

Free Blacks used legislative petitions to protest several oppressive laws passed by the Delaware legislature in the antebellum period. The Act of 1832 prohibited free Blacks from owning firearms and limited their right to practice religion. The Act of 1849 required free Blacks to present a pass or certificate certifying freedom to pass through or travel from the state, which had to be signed by a white man. The Acts of 1851 prohibited free Blacks from traveling out of state for more than sixty days, visiting Delaware if they were non-residents, and practicing religion. The act also allowed white people to take free Black children away from their families to use their labor.[7] Free Blacks who allegedly violated these laws were at risk of arrest, fines, incarceration, and enslavement.

Petitioners used a variety of strategies to protest these laws. Petitioners vividly described how each law was oppressive and negatively impacted their lives. Those petitioning the 1832 law described the act as “very openly oppressive,” “evils of the greatest magnitude,” and having a “demoralizing effect.”[8] Expressing frustration over the limitations on their mobility, those petitioning the 1851 acts wrote: “We endeavor to perform the duties of good, orderly citizens, and it bears hard on us not to be allowed the privilege of seeking to do better elsewhere without losing our residence and being subject to arrest, fine, imprisonment, and sale…” Free Blacks also described how the 1849 law valued the character of a white man over free, Black people– even if the white man’s character was “much blacker Then [their] Skins.”[9]

Petitioners emphasized that they were citizens of good character worthy of having their humanity and rights respected and protected. For the 1832 act[10] petitioners argued that they were peaceful, quiet, and property-owning citizens and they emphasized that they have continued to gain the confidence of their white superiors. For the 1849 law[11] petitioners stressed that they were responsible citizens who paid their taxes yearly. They further attempted to make their cases by assuring the legislature of their good conduct and pure intentions: “we are civil, we desire no intent to hurt or injure any of the human family but wish well to all.” Petitioners also challenged the contradictory nature of the legislature’s passage of oppressive laws which went against the U.S.’s founding ideals and charters. Petitioners of the 1832 act framed their argument by pointing out contradictions between the legislature’s enforcement of this oppressive act and the principle of liberty outlined in the Constitution.[12]

Some petitioners took a different approach by framing their argument in a way that would seem the most attractive and beneficial to legislators. For instance, petitioners of the 1832 law emphasized that they were not arguing for their claim to the full rights that are afforded to all Americans but simply wanting the act to be repealed.[13] Those petitioning the 1851 acts detailed how repealing the acts would make them better citizens.[14] They argued that by doing so, the legislature would “…encourage us to become more intelligent, better citizens, and to seek more generally the best of wisdom to be found in the sanctuary…”. They made the case that it is in the interest of the state to repeal the act: “…we hope by our good conduct hereafter that we shall show that your acts were dictated not only by humanity, but the interests of the State.” While petitioners were explicitly calling for such laws to be abolished, they ultimately expressed that they were willing to settle for whatever the legislature sees as “equitable.” Additionally, across the petitions, the legislature is described as having wisdom, virtue, and humanity, which petitioners urge them to use to bring relief to their oppression.

The petitioning of free Black Delawareans provides a rich account of the state of race and anti-Black racism directly from the perspectives of those being oppressed. There is an increased awareness and outrage over racial injustice today, as made evident in the recent creation of institutional initiatives such as the University of Delaware’s Anti-Racism Initiative (UDARI). If the University of Delaware truly seeks to investigate its institutional, local, and state history of race and inequality, it must consult historical data sources which specifically center the voices, perspectives, and lived experiences of Black Delawareans. This will reveal a more accurate narrative of how racial oppression has existed throughout Delaware and the roles played by the state and university in perpetuating that oppression.

Krishanna Prince is a Sociology PhD student and Equal Justice Fellow in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at the University of Delaware. Her research broadly concerns race/ethnicity, inequality, and policing, with a particular focus on lived experiences of the Black/African American community.

[1] Patience Essah, A House Divided: Slavery and Emancipation in Delaware, 1638–1865. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996), 187.

[2] Daniel Carpenter, Democracy by Petition: Popular Politics in Transformation, 1790-1870. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

[3] Ibid, 23.

[4] Essah, 110.

[5] Loren Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Petitions to Southern Legislatures, 1777-1867 (Bethesda, MD: LexisNexis, 2002). These petitions were gathered by the University of Greensboro at North Carolina (UNCG)’s Race & Slavery Petitions Project.https://library.uncg.edu/slavery/petitions/about.aspx. For the scope of this study, the focus was narrowed down to legislative petitions authored by free Black people in the state of Delaware between 1830 and 1869. Once this criterion was applied, a total of twelve legislative petitions were able to be used for analysis.

[6] Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks: Petitions to Southern Legislatures, 1777-1867, M. Film No. 5537, https://delcat.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/40251211

[7] “An Act to prevent the use of fire arms by free negroes and free mulattoes, and for other purposes,” February 10, 1832, ch. CLXXVI, 8 Del. Laws 208; “An Act in relation to idle and vagabond free negroes,” February 28, 1849, ch. CCCCXII, 10 Del. Laws 414-416; “An Additional Supplement to the act entitled ‘An act to prevent the use of fire arms by free negroes and free mulattoes, and for other purposes,’ “ February 24, 1851, ch. DLXII, 10 Del. Laws 587; “An Act in relation to free negroes and slaves,” March 5, 1851, ch. DXCI, 10 Del Laws 591-593.

[8] PAR 10383312, 10383301, 10383302, 10383303, 10383304, 10383306, 10383307, 10384304,”Petitions of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, January 1, 1833-January,1843,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Reel 2, Images 0333, 0343, 0346, 0351, 0365, 0367, 0489

[9] PAR 10384901, “Petition of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, 1849,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks,, Reel 2, Image 0659

[10] PAR 10383312, 10383301, 10383302, 10383303, 10383304, 10383306, 10383307, 10384304, “Petitions of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, January 1, 1833-January,1843,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Reel 2, Images 0333, 0343, 0346, 0351, 0365, 0367, 0489

[11] PAR 10384901, “Petition of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, 1849,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Reel 2, Image 0659

[12] PAR 10383312, 10383301, 10383302, 10383303, 10383304, 10383306, 10383307, 10384304, “Petitions of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, January 1, 1833-January,1843,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Reel 2, Images 0333, 0343, 0346, 0351, 0365, 0367, 0489.

[13] Ibid.

[14] PAR 10385301, 10385304, 10385309, “Petition of Free Blacks to the General Assembly, Delaware, 1853,” in Schweninger et al., eds. Race, Slavery, and Free Blacks, Reel 2, Images 0744, 0746, 0754.