What were Rathmell Wilson’s connections to slavery and oppression in antebellum Delaware?

By: Collin Willard | Posted: 7-7-2022

Currently, the University of Delaware’s historical narrative is incomplete; materials on the University’s website make no mention of slavery or the Civil War. There is an existing gap in knowledge regarding how figures important in the history of the University of Delaware supported, facilitated, and practiced slavery. In order to truly understand the history of the University of Delaware, analyzing Delaware College’s connections to slavery is key.

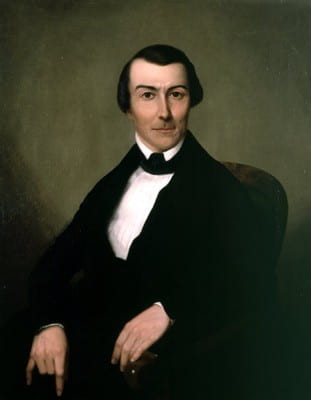

Rathmell Wilson, a Newark businessman who served as President of Delaware College’s Board of Trustees, serves as a key example in understanding the University of Delaware’s entanglement with slavery. After moving to Newark in the early 1840’s,[1] Wilson became a key figure in the University of Delaware’s history, overseeing the Board of Trustees before, during, and after the Civil War. Archival research shows that (1) Rathmell Wilson was an enslaver who didn’t just benefit from the legality of slavery, but also from a legal regime that denied full political, civil, and social rights even to “free” Black Delawareans; and (2) Wilson used his wealth and status to uphold this status quo prior to and during the Civil War.

Wilson moved from Pennsylvania to Newark in 1841 and built his Oaklands mansion just west of Main Street.[2] Wilson bought his first property when he was just 31 years old for the hefty sum of $18,000,[3] and quickly amassed seven properties during the 1840’s in Newark’s wealthy neighborhoods.[4] Wilson first joined the Delaware College Board of Trustees as a member in 1847, just six years after moving to Newark, and became President of the Board of Trustees by 1851.[5] He quickly became an important donor, contributing the largest sum ($4,000)to the school’s scholarship campaign in 1851.[6] When Wilson officially settled in the affluent section of Newark in the 1840s, he appears to have quickly picked up on two signals of status among neighbors like Thomas Blandy, Andrew Bradley, and James L. Miles: owning slaves,[7] and holding a seat on the Board of Trustees at Delaware College. Wilson’s emulation of these figures suggests evidence of a culture of slavery among Newark’s elites, given that he adopted the enslavement practices after relocating from Pennsylvania, where slavery was outlawed.

Traces of Rathmell Wilson’s involvement in slavery surface in historical records soon after he purchased land in Newark in 1841. County property records show that Rathmell Wilson manumitted four enslaved Black people in 1850. Individual enslavers could manumit their human property, “giving” enslaved Black Delawareans their personhood – but their release from bondage was often delayed, especially for younger people who were held in bondage past their prime working years. This meant that enslavers could agree to manumit their enslaved people to appease their consciences, or anti-slavery advocates, while still benefitting from enslaved people’s labor.[8] Manumission deeds show that Ann Chase and a six-month old girl (alternately identified as Mary and Laura in the records) were to be freed nine months after their manumission deed was executed, while four-year old Charles and eight-year old Henry Chase were to be freed on their twenty-third birthdays (nineteen and fifteen years later, respectively); and finally sixteen-year-old Sewell Chase on his twenty-fifth birthday, in sixteen years.[9] These manumission deeds clearly establish Rathmell Wilson as an enslaver, as well as a participant in the market for “term slaves,” as victims of Delaware’s system of delayed manumissions were sometimes called. Shortly after manumitting the Chase family, Wilson transferred ownership of the family members to his neighbors, the Holtzbecker’s, for an undisclosed fee.[10]

While it is evident that Rathmell Wilson was an enslaver, pinpointing the moment he acquired slaves is difficult. Rathmell Wilson’s tax records from 1840-1845 do not report any slaves, but evidence in personal documents suggests Wilson began enslaving Ann as early as 1843.[11] His wife, Martha Wilson, references someone named “Ann” in two letters written to Rathmell. On August 15, 1843, Martha provided instructions for Ann to preserve milk,[12] and later wrote, “you wished me to let you know when Ann was to commence potting butter for me. I do not wish her to commence until the week you leave to come to White Haven…tell her to keep it in the cellar in preference to the vault…”[13] The nature of these instructions and the directness of Martha’s tone indicates that this is a subordinate relationship, and it is likely that this is the same Ann who was later manumitted in 1850.

In addition to Wilson’s enslavement of the Chase family, Wilson relied upon the labor of other Black workers. Joseph Commons and James Adams were both “free” Black men who worked as laborers that lived on Wilson’s property. The limits on Black freedom served as a barrier to employment opportunities, leaving Black Delawareans with few options and very little compensation. While the nature of Commons’ and Adams’ compensation is unknown, the fact that they lived on Wilson’s property suggests this was not an employer-employee relationship that permitted the employees real economic independence. In addition, two women, Adaline Watson and Sarah Sanders, also appear in Wilson’s census records.[14] 1870 Census records show that teenage Sarah Sanders was part of a free Black household in 1870; she may have been indentured or apprenticed–an additional form of bondage similar to “term slavery”–at a young age in 1860.[15]

Not only did Wilson enslave Black people, he also fought against emancipation. In February of 1852, Wilson led the fight to block an anti-slavery advocate from speaking in Newark, on the grounds that it would cause agitation in the Newark and Delaware College community.[16] A decade later, after the Civil War broke out, Wilson made his stance on slavery clearer than ever. Wilson ran for State Senate in 1862 as a Democrat, putting him on the pro-slavery party’s ticket.[17] Though a slave state with Southern sympathies, Delaware had had not joined the Confederate cause largely due to its geographic location.[18] But despite their reluctance to secede, the party supported the institution of slavery while opposing abolition heading into the 1862 gubernatorial election. Democrats portrayed their opponents as too friendly to Black Delawareans, and suggested they wanted to elevate the status of Blacks above whites. Ultimately, the Democrats lost the gubernatorial race, and Wilson lost to his Republican counterpart.[19]

Rathmell Wilson was an enslaver who owned members of the Chase family, and relied upon the landscape of unfreedom to exploit other Black Delawareans. A leader amongst Newark’s wealthy class, Wilson also upheld the status quo of slavery by blocking an anti-slavery advocate from speaking in Newark. When the issue of slavery brought the United States past the breaking point, Wilson ran for state senate unsuccessfully under the pro-slavery party in an attempt to halt emancipation. These details make clear that Delaware College’s leadership during the Civil War was committed to preserving the white supremacist status quo of slavery.

This research has important implications for the University of Delaware. It demonstrates the need for further investigation into how other important figures in the University’s history upheld the legal status quo of slavery and the culture of white supremacy. Given that Rathmell Wilson held such an important position at Delaware College for such an extended period of time, guiding it through its leanest years, it is not unreasonable to suggest that his views were shared more widely throughout the school’s leadership. Further, it is crucial that the University of Delaware acknowledge the role that enslavers like Rathmell Wilson had in shaping the institution, rather than excluding them from its history. The University of Delaware harkens back to colonial 1743 when charting the history of the institution, showing pride for its lengthy history. However, the University cannot present its history in good faith without acknowledging its very real history of oppression, carried out by the men like Rathmell Wilson who sat on its Board of Trustees.

Collin Willard is a graduate student in the Biden School’s MA Urban Affairs and Public Policy program. He completed his undergrad in ’22, earning a BA in History and Public Policy. During his time at UD, Collin has contributed to several UDARI projects, while also holding positions at the Institute for Public Administration and the Writing Center.

[1] “Biographical and Historical Notes.” Wilson Family Papers, MSS 303, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, Delaware. https://library.udel.edu/special/findaids/view?docId=ead/mss0303.xml;tab=use

[2] Rathmell Wilson, New London, Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1840 U.S. Federal Census, accessed via Ancestry.com; “Biographical and Historical Notes,” Wilson Family Papers.

[3] Rathmell Wilson and Lewis Holtzbecker, April 8, 1841, Deed Books of New Castle County, Delaware, Volume G-5, pp. 175-176.

[4] “1852 White Clay Creek Hundred” Assessment Records, New Castle County, Delaware, reel 21, p. 33; Samuel M. Rea and Jacob Price, Map of New Castle County, Delaware, from Original Surveys, (Philadelphia: Smith and Wisar, 1849).

[5] Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Delaware College, 1847-1848. (Philadelphia: United States Book and Job Printing Office, Ledger Building, 1848); Circular and Plan of Endowment of Delaware College. (Philadelphia: King and Baird Printers, 1851).

[6] John A. Munroe, The University of Delaware: A History (Newark, DE: The University of Delaware Press, 1983), Ch.4, https://sites.udel.edu/uarm/the-university-of-delaware/.

[7] 1800-1850 United States Census Federal Census, accessed via Ancestry.com.

[8] Patience Essah, A House Divided: Slavery and Emancipation in Delaware, 1638–1865 (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 1996), 61, 88-90.

[9] Manumission of Ann, Mary, and Charles Chase by Rathmell Wilson, April 1, 1850, Deed Books of New Castle County, Delaware, Volume F-6, pp. 47-48; Manumission of Henry and Sewel Chase, August 31, 1850, Deed Books of New Castle County, Delaware, Volume F-6, pp. 50-51.

[10] Ruth Decosse, “To Be Young, Black, and Manumitted,” Seminar Paper, HIST 460/660, University of Delaware, December 14, 2021.

[11] Assessment Records, White Clay Creek Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware, reel no. 17, 1840-45 p. 35, and White Clay Creek Hundred, 1845, reel no. 18, p. 32.

[12] Letter to Rathmell Wilson, August 15, 1843, Wilson Family Papers, MS303, Box 1, Folder F23.

[13] Letter to Rathmell Wilson, September 5, 1843, Wilson Family Papers, MS303, Box 1, Folder F23.

[14] Rathmell Wilson, White Clay Creek Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware, 1850 United States Federal Census, accessed via Ancestry.com; Rathmell Wilson, White Clay Creek Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware, 1860 United States Federal Census, accessed via Ancestry.com. Adaline Watson is in Rathmell Wilson’s household in 1850, while Sarah Sanders is there in 1860.

[15] Sarah Sanders, White Clay Creek Hundred, New Castle County, Delaware, 1870 United States Federal Census, accessed via Ancestry.com

[16] “From the Lecturing Field,” American Freeman, February 8, 1852. Thanks to Dr. Laura Helton for locating this article.

[17] “Delaware Election: The State Rescued from Rebel Rule” Delaware State Journal and Statesman (Wilmington, DE), November 7, 1862.

[18] History and Government of Delaware. Part 9, “The Civil War and its Political Background,” performed by John A. Munroe (1963; Wilmington: WHYY), http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/23058.

[19] Harold Bell Hancock, Delaware During the Civil War: A Political History, p. 110-118.