by Laura Walikainen Rouleau

In 1897, New York City’s Committee on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations recommended that the city build public toilet facilities based on the example of London’s underground latrines because they were “clean, inodorous, hidden from view, attractive, frequented by all ranks of society, and are provided for both men and women in separate places.”1

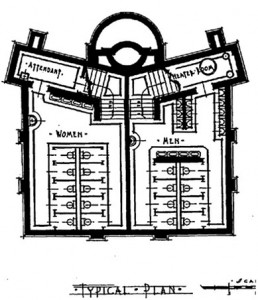

Fifteen years later, the quest for ideal public toilet facilities continued as the Engineering Review, an early twentieth-century trade journal, extolled the exemplary design of a “public comfort station,” as they were termed at the time, in Brookline, Massachusetts. This comfort station was, as the commentator suggested, “ideally” located at the convergence of several streetcar lines in the most densely populated area of the city. The Review made specific note of facility’s separate entrances for men and women “designed with covered vestibules and right angle turns in the staircases, thus securing the maximum of privacy” (Figure 1). 2

Figure 1. “Public Comfort Station at Brookline, Mass.,” from “The Public Comfort Station in America,” Engineering Review 22, no. 5 (May, 1912): 37.

An Expanding American Public

These assessments of early public toilets highlight how privacy was defined and experienced amidst an expanding American public at the turn of the twentieth century. Private spaces, such as toilets, dressing rooms, baths, and locker rooms, appeared in public places in this era in order to serve this new American public. During the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States experienced an unparalleled era of growth. In 1870, the national population was 38 million, and, by 1900, that number more than doubled to 77 million. By 1920, the overall national population had increased to roughly 106 million, an increase of 279 percent in 50 years.3 This increase in population was due, in large part, to immigration. In 1882 alone, nearly 800,000 people came to America. By 1907, the number of newly arriving immigrants rose to almost 1.3 million people.4 These new arrivals often found jobs in the nation’s thriving industrial core. Although 40 percent of Americans still worked in agriculture by the turn of the century, industrial work and corollary white-collar, service-sector jobs accounted for 50 percent of American jobs by 1900.5 The new American public of the twentieth century was increasingly populated, urban, and industrial.

These growing, urbanizing, and industrializing Americans began to work, eat, shop, and entertain themselves outside their private homes, thus necessitating changes in the built environment. Public transportation expanded to move people from their homes to their places of work and leisure and back again. Dry goods stores developed into vast department stores where people (mostly of the middle and upper classes) could shop for all varieties of clothing and furnishings under one roof. Parks, playgrounds, gymnasiums, and libraries emerged to provide enrichment for the American public.

An Emerging Need for Privacy

But as Americans spent more time in these emerging public places, they also needed complementary private spaces to address the basic needs of the human body. People who were used to cleansing, dressing, and relieving their bodies within the privacy of their homes found themselves “inconvenienced” in public. Middle- and upper-class women shopping in modern department stores required spaces to try on newly available ready-made clothing.6 Working-class people living in tenements or industrial housing required spaces to cleanse and relieve their bodies in public.7 And by the early twentieth century, children learned how to cleanse and relieve their bodies as part of the developing physical education programs in public schools.8 Department store dressing rooms, public baths and toilets, and school locker rooms emerged as sites at the boundary of the public and private in order to fill these needs. In this way, it was the human body and its experience of the public that served to physically shape the built environment.

In order for such personal activities to be acceptably performed outside of the private home, the creators and designers of these emerging spaces needed to establish a sense of privacy for their users. Through the design, creation, and regulation of these spaces at the boundary of the public, the very meaning of privacy became materially manifested. By interrogating these private spaces in public places, we can gain an understanding of how privacy was defined during this time.

Public restrooms, department store dressing rooms, public baths, and school locker rooms were designed and implemented by business owners, government officials, architects, and social reformers who were largely members of the middle and upper classes. Thus these spaces materially reflected a middle-class vision of privacy. This vision was based on class and gender distinctions, as well middle-class understandings of morality and hygiene. These ideals were physically manifested in these public, private spaces.

But the actual use of these new private spaces in public places did not always reflect the middle-class values of privacy they were intended to evoke. Concerned contemporary commentators often noted the misuse of this privacy, highlighting a disconnect between the designers’ intentions and how these spaces were used. This distinction reveals a divide between the middle-class definition of privacy and the reality of the historic experience of privacy. The performance of private activities within these spaces embodied this disparity.

Private “Comfort” in Public

To demonstrate how these notions of privacy were materially manifested within these spaces, let’s further interrogate the specific example of the public restroom or comfort station. The need for public toilet facilities was stated succinctly by a doctor of the time: “There is no need to insist upon or to emphasize the annoyance, the humiliating experiences and the dangers to health caused to the shopping and traveling public by this barbarous absence of modern sanitary conveniences.”9 In reexamining the Engineering Review’s praise for an exemplary comfort station, we can begin to see how an ideal privacy could be physically created within one of these sites. The Review commended the Brookline comfort station’s underground location and hidden entrances. One of the most essential ways privacy was physically created in public private spaces was visually. Social commentators at the time were concerned that, without public toilet facilities, some members of the working class were, as Chicago public policy makers put it in a 1916 bulletin, reduced to “committing nuisances in alleys and slightly out of the way corners.”20 These practices, they explained, resulted in “bad odors,” but middle-class reformers were most concerned that “such places were in view of the passing public, whose sensibilities [were] disgusted or shocked.”11

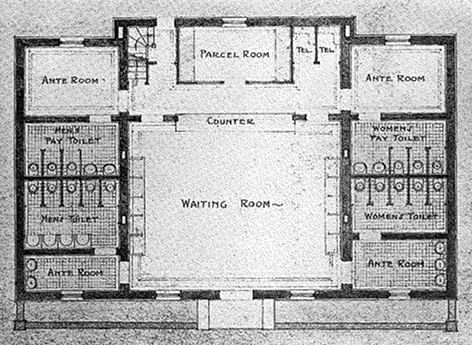

Figure 2. Van Leyen, Schilling & Keogh, “Public Comfort Station, Capital Square, Detroit, Mich.,” The American Architect 118, no. 2342 (Nov. 10, 1920): 606.

In reaction to such practices, designs for public comfort stations highlight the use of individual stalls and walls as visual barriers for patrons. One public comfort station advocate declared that stalls needed to have doors “large enough to afford privacy.”12 Many social commentators were proponents of underground public comfort stations, in order to visually separate the entire building from the public sites in which they were situated.13 While underground comfort stations were preferred in order to completely protect toilet facilities from public view, one engineer noted that plants, such as small trees or shrubs, could shield the entrance of a comfort station “without being so very conspicuous.”14 Other proponents called for a public comfort station building to “not be too conspicuous but should be an architectural gem, harmonizing with the surroundings.”15 Visual privacy inside and outside the public comfort stations was an essential part of their acceptability as public private spaces, as evidenced by as evidenced by one early comfort station in Detroit (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Public Comfort Station Indianapolis, from “The Public Comfort Station in America,” Engineering Review 22, no. 3 (March, 1912): 32.

Another important component of this definition of privacy was the prescriptive gendered separation of public restrooms. As the Engineering Review noted, “maximum privacy” could only be achieved through the total separation of men and women. Public toilet facilities were generally gender segregated and often had separate entrances for men and women. An early comfort station in Indianapolis offered completely separate facilities for men and women (Figure 3). These entrances were often located as far away from each other as possible for the facilities to remain in the same building.16 For example, the State Board of Health of Wisconsin was tasked with providing state-mandated public comfort stations with “suitable approaches and privacy, separating accommodations afforded both sexes.”17 Some stations were housed in completely separate buildings for male and female users. The assumption of gendered separation helped to create a sense of privacy within these spaces. And it appears that, for at least some women, this public privacy took some time before it was acceptable. Early estimates of comfort station users showed that only 15 to 20 percent were women.18 One doctor at the time argued that women had a “false modesty or squeamishness about being seen going to the toilet while in public places.”19 The social norm of gendered segregation of private activities shaped the built environment of these private spaces in public.

As middle-class designers, government officials, and business owners were often responsible for the design of these spaces, their class distinctions were often implemented into the physical experience of these spaces. Within public comfort stations, there was often a class-based experience of privacy. Many of these new facilities required customers to pay to use them. Other comfort stations offered differing levels of comfort and privacy for paying customers. Social commentators recommended turnstiles to divide free and pay portions in public comfort stations so that “those paying . . . will have use of the greater space as well as the toilet booth.”20 Some pay closets were equipped with door locks, while the free stalls had simple bolts.21 In addition to purchasing “greater privacy,” comfort station users could pay for “greater cleanliness and a higher grade of fixtures.”22 In some cases, the pay stalls had doors, while the free toilets of the comfort station did not.23 The disparities of access and aesthetics based on price served to “class” these spaces and the level of privacy experienced within them, thus materializing the social distinctions of class during this time (Figure 4).

Figure 4. “Floor Plan of National Highways Public Comfort Station,” from “The Comfort Station as a Public Utility,” The American City 16, no. 2 (Feb., 1917): 180.

Class was not the only social division to be manifested with these spaces. While not always overtly stated or clearly physically manifested, there was always at least an implied assumption that public toilet facilities would be racially segregated during this era of Jim Crow laws. The idea of creating separate areas for nonwhite users was at least novel enough to a national audience to merit an article in The American Architect in 1922. In the article, titled “Dallas Public Comfort Station: A Comfort Station in Which Provisions are Made for Two Races,” the author noted that “public comfort stations in Northern cities, where the race question is not raised, are simple by comparison to similar utilities in the South.”24 On the other hand, the city of Dallas answered the “race question” by creating “four separate divisions” within the facility.25 Although it was “desirable to have separate stairways for the two races, space did not permit,” according to the article.26 The comfort station therefore offered only two separate stairways and entrances for men and women, which lead patrons to different sections according to race. Of more concern to the article’s author was the fact that the male and female entrances were too “close together.”27 To address this perceived impropriety, designers placed a large evergreen plant between the two entrances and “no complaints ha[d] been made.”28 An earlier comfort station located in Paris, Texas, did offer racially and gender segregated entrances, but an article in The American City that described the comfort station did not mention these divisions.29 Whether overtly physically manifested or simply implied, this definition of privacy was also based on the racial segregation.

An expected level of cleanliness and hygiene was also part of how privacy was defined by the creators of these spaces. As Chicago’s health commissioner noted in 1915, “poor toilet facilities spread disease.”30 The same year, the president of the American Public Health Association decried that “the most flagrant failure in American sanitation today is the distressing absence or utter inadequacy of public comfort stations in our cities and towns.”31 Reformers called for these public toilet facilities to be “absolutely sanitary . . . [and] should present at all times a ‘spotlessly white’ appearance.”32 Municipal officials proposed plans for public toilet facilities to be created using light-colored materials, such as white glazed tiles and white enameled brick, “to avoid dust and to give the utmost light and cleanliness.”33 Comfort station proponents called for “toilet paper, liquid or powdered soap and paper towels to be available free at all times.”34 In order to maintain these stations, public officials called for educating users about the proper way to keep the facilities sanitary.35 The designers and creators of these private spaces sought to materially impose their hygienic ideals on public comfort stations.

Related to these notions of cleanliness and hygiene, social commentators hoped these sites would be morally uplifting for the users. As one reformer argued, public toilet facilities needed to be designed and maintained in order to “create an atmosphere of absolute cleanliness and due regard for decorum.”36 The physical equipment and layout of these spaces was directly connected to the morality of the patrons of the space. “Pure white glazed earthen fixtures set in pure white compartments foster[ed] a feeling of decency and aid[ed] in inducing cleanly habits,” according to one engineer. And the very construction and maintenance of such sites could prove morally uplifting to those without other options. In lieu of public comfort stations, many men frequented the saloon in order to find relief. In fact, so many men patronized saloons for this reason that saloon owners noted that their toilet facilities generated more business than the free lunch.37 Public toilet facilities offered a “moral” alternative by “the discouraging of the glass, taken often when not greatly desired, to recompense the saloon keeper.”38 Other commentators hoped city workers and street cleaners would avail themselves of these sites, as they were largely “foreign-born” and “lacked that fine sense which prevents their committing nuisances in alleys.”39 This middle-class understanding of morality became materialized within these spaces.

Designed Intentions v. Actual Use

By examining the design plans, layouts, and fixtures of these public comfort stations, we can gain a sense of how architects, planners, builders, and public officials intended to impress their definition of privacy onto these physical spaces. But the very privacy that these spaces afforded also created the possibility for transgression. (Evidence of the possibility of transgressions persist in public toilets to this day) (Figure 5). Commentators noted a number of ways these spaces were “misused” at the time. In fact some of the later designs for public comfort stations sought to prevent unacceptable behavior through a physical redesign of the space. There was an inherent anxiety associated with these spaces because they did offer privacy to the general public. By focusing on the these transgressions, we can get a sense of how privacy within these spaces was actually experienced and how this privacy allowed users to physically reshape these spaces through their experiences.

One of the preliminary problems noted by commentators was theft and/or defacement of the public comfort station furnishings. As early as 1867, New York City instituted a $50 fine or three months in jail for “defacing or defiling” any public comfort station.40 And in 1919, a Wisconsin law stated that “display of indecent pictures and writing in the stations will be punishable offenses.”41 By 1916, social commentators recommended that comfort stations “should have no loose or detachable parts liable to be tampered with or to be taken away” because, as one reformer noted, “vandals soil and destroy fixtures and fittings, while petty thieves pilfer removable parts and even wrench away fixed parts which they can sell.”42 One public official recommended designing the toilet seats so that no one would be able to stand on them, likely so that no one could hide in the stalls or peer over the walls at other patrons.43 New York City officials banned “loud, profane or indecent language [and] boisterous or intoxicated persons,” from the city’s public comfort stations.44 Under accusations of noncustomers “lounging,” the “carelessness and lack of consideration shown by patrons,” and overall “misuse” of their public toilet facilities (especially by women), department store managers began to scale down their elaborate restrooms.45 Social commentators were also concerned about crimes against comfort station users. One public official warned against locating comfort stations in isolated areas “for no better lurking place could be found for a foe.”46 They suggested that station entrances be highly visible with “the constant passing of pedestrians” in order to make them “self-policing, thus removing apprehension of danger in the use of these stations.”47 Architects began to design these spaces to prevent illicit activity, but this very privacy allowed for activities to take place that were usually prohibited in public spaces. The variety of activities that were performed in these spaces demonstrates the limits of privacy in these public places. These transgressions highlight the contradiction between the creators’ definition of privacy and the public’s actual experience of privacy through the use of the space.

In order to bridge this gap between intention and reality, designers added a human element to this built environment in the form of comfort station attendants. These workers regulated and cleaned these spaces and served as “gatekeepers.” Designers hoped these attendants would enforce the intended definition of privacy within these comfort stations. Commentators acknowledged possible misuse by the station’s patrons, making daily cleanings by attendants “necessary by the carelessness of the many users.”48 Attendants were also to “be on constant lookout so that no loose or easily detached fittings are appropriated and that no loitering or defacing of the walls [took] place.”49 One commentator suggested giving attendants police powers.50 Many public toilet facilities were designed with specific rooms for attendants to operate out of while on duty, thus providing constant surveillance.51 Often uniformed in white suits to match the light-colored fixtures of the stations, attendants functioned as human extensions of the architectural intensions of these spaces. They were another material component used by designers to reinforce their specific definition of privacy. And the price of this intended privacy was a constant surveillance that limited the users’ experience of privacy (Figure 6).

Figure 6. “One of New York’s Comfort Stations.” from Donald B. Armstrong, “Public Comfort Stations: Their Economy and Sanitation,” The American City 11, no. 2 (Aug., 1914): 95.

Public comfort stations, along with dressing rooms, public baths, and locker rooms, arose at the turn of the twentieth century to fulfill societal needs. Although they were novel spaces, they were designed, created, and regulated according to a specific definition of privacy based on distinctions of gender, class, and race, as well as middle-class beliefs about hygiene and morality. But in noting the misuse of these spaces, we can gain a sense of the actual historical experience, not just the intended use, of these sites. In the changing social, cultural, and physical environments of the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century, these private spaces in public places became not only accepted but expected. And our continued acceptance of these spaces is revealed every time we undress, relieve, or cleanse our bodies in public.

1. “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” Mayor’s Committee on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations. (New York, 1897): 174.

2. “The Public Comfort Station in America,” Engineering Review 22 (May, 1912): 35-36

3. Thomas J. Schlereth, Victorian America: Transformations in Everyday Life, 1876-1915 (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 28. Walter Licht, Industrializing America: The Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), xiv.

4. Schlereth, Victorian America, 8.

5. Licht, Industrializing America, xiv.

6. On the development of the department store, see Susan Porter Benson, Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988); William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993); and Richard W. Longstreath The American Department Store Transformed, 1920-1960 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010). On the development of ready-made clothing, see Claudia B. Kidwell and Margaret C. Christman, Suiting Everyone: The Democratization of Clothing in America (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1974), 139 and Claudia Brush Kidwell, Cutting a Fashionable Fit: Dressmakers’ Drafting Systems in the United States (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1979), 96-8 and 137.

7. On the development of public baths, see Marilyn T. Williams, Washing “The Great Unwashed”: Public Baths in Urban America, 1840-1920 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1991).

8. On the development of physical education in American public schools, see Mabel Lee, A History of Physical Education and Sports in the U.S.A. (Wiley, 1983).

9. Dr. Woods Hutchinson, as quoted in “Public Comfort Stations for Chicago,” Bulletin of the Department of Public Welfare, City of Chicago 1, no. 3 (October, 1916), 15.

10. “Public Comfort Stations for Chicago,” Bulletin of the Department of Public Welfare, City of Chicago 1, no. 3 (October, 1916), 8.

11. Ibid.

12. William Paul Gerhard, “Public Comfort Stations: Their Location, Plan Equipment and Care,” The American City 14, no. 5 (May, 1916), 454.

13. “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” Mayor’s Committee on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations. (New York, 1897): 176.

14. Jon Webster to Charles H.T. Collis, July, 8, 1896, New York, Map Division, New York Public Library.

15. George W. Simons, Jr., “More Public Convenience Stations Needed,” The American City 23, no. 5 (Nov., 1920), 474.

16. “Public Comfort Station in Newark, N.J.” Building Age (May 1, 1910): 219; Gerhard, 453.

17. A.L.H. Street, “All Municipalities in Wisconsin Must Provide Comfort Stations,” The American City 21, no. 3 (Sept. 1919): 279.

18. “The Need for Building Public Convenience Stations,” The American Architect 17, no. 2321 (June 16, 1920): 775; Gerhard, 452.

19. Samuel Goodwin Gant, Constipation and Intestinal Obstruction (W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, 1909): 60.

20. Comfort Stations of New York City: Today and Tomorrow, Women’s City Club of New York (New York City, 1932), 46.

21. “Public Comfort Station in Newark, N.J.” Building Age (May 1, 1910): 219

22. Gerhard, 452.

23. Gerhard, 454.

24. “Dallas Public Comfort Station: A Comfort Station in Which Provisions are Made for Two Races,” The American Architect and the Architectural Review 121, no. 2389 (Mary 15, 1922), 231.

25. Ibid.

26. See note 24 above.

27. See note 24 above.

28. Ibid.

29. “Improving the Public Square in Paris, Texas,” The American City 5, no. 2 (August, 1911), 78-81.

30. As quoted in “Public Comfort Stations for Chicago,” Bulletin of the Department of Public Welfare, City of Chicago 1, no. 3 (October, 1916), 15.

31. As quoted in “Public Comfort Stations for Chicago,” Bulletin of the Department of Public Welfare, City of Chicago 1, no. 3 (October, 1916), 8.

32. Gerhard, 453-454.

33. Gerhard, 454 and “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” Mayor’s Committee on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations. (New York, 1897): 180.

34. Simons, Jr., 473.

35. Donald B. Armstrong, “Public Comfort Stations: Their Economy and Sanitation,” The American City 11, no. 2 (Aug., 1914): 102.

36. Gerhard, 455.

37. Simons, Jr., 472.

38. Ibid, 142.

39. “Public Comfort Stations for Chicago,” 8.

40. “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” 143.

41. A.L.H. Street, 279.

42. Gerhard, 455 and J.J. Cosgrove, “Standards for Public Comfort Stations,” Public Comfort Station Bureau, (New York, 1916).

43. “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” 166.

44. “What it Costs to Maintain Public Comfort Stations,” Domestic Engineering 95, no. 1 (April 2, 1921), 11.

45. Comfort Stations of New York City: Today and Tomorrow, 30.

46. J.J. Cosgrove, “Standards for Public Comfort Stations,” Public Comfort Station Bureau, (New York, 1916).

47. Comfort Stations of New York City: Today and Tomorrow, 45.

48. Gerhard, 456.

49. Ibid.

50. See note 48 above.

51. “Report on Public Baths and Public Comfort Stations,” 180; Comfort Stations of New York City: Today and Tomorrow, 45.