It’s All About Swamps

By Austin Losada WPAMC ’23

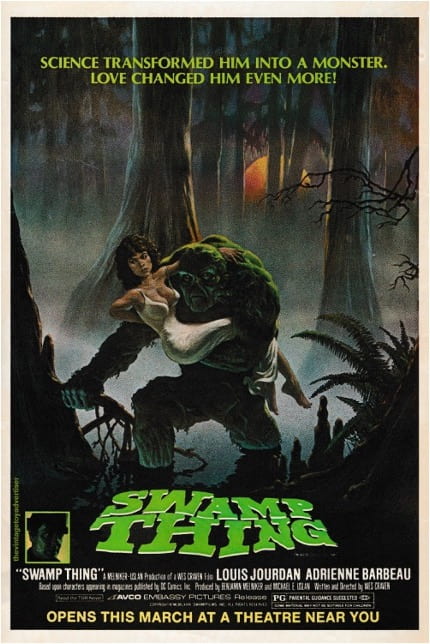

At the center of Wes Craven’s 1982 film Swamp Thing is the distinct landscape of the South (Fig. 1).[1] While set in Louisiana, the filming took the cast and crew to South Carolina where the boggy Cypress Gardens and historic Aiken-Rhett House served as the backdrop for the movie. The film and comic series follow scientist Alec Holland who creates a bio-restorative formula to solve world hunger but falls victim to a plot that seeks to destroy his lab’s progress. Like most superhero origin stories, Holland comes in contact with his own formula transforming him into half-man, half-vegetation – “Swamp Thing.” As Swamp Thing, Holland lurks in the bayous of Louisiana, protecting its habitat from antagonists seeking to destroy a local ecosystem which has the potential to stave off world hunger.

During our class’s trip along the coast of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, Swamp Thing continued to rattle in my mind. Not just because we visited the Aiken-Rhett house where a few scenes were staged, but also because of how many times we encountered the historical memory and contemporary conversations surrounding swamps. Our visits to Somerset Place plantation, the Great Dismal Swamp, and Hobcaw Barony addressed how integral controlling and conquering swampland in the southern low country was to settlement in the eighteenth century. Draining swampland and making it arable produced not only economic prosperity for plantation owners but created routes of travel for both goods and people. Lest we forget, swamps were sites of brutal enslaved labor, where men and women worked under physically demanding, disease-ridden, and buggy conditions using only hand tools to forge Southern swampland into a profitable business – the rewards of which they saw none.

Growing up in central New Jersey, “swampy areas” were something to be avoided: their stagnate surface bred mosquitoes, their dark, murky waters were forbidding, and simply, they were smelly. For most of history, the negative associations attributed to the wetlands of the South was consistent with my worldview. But where I saw uninhabitability, three Edenton, North Carolina businessmen saw possibility and created Somerset Place, an antebellum plantation that operated for eighty years (1785-1865). Somerset Place boasted 109,000 acres of land, most of which was forested swampland.[2] To make this land ready for crop cultivation and its transportation, one of the businessmen, Josiah Collins I, imported eighty West African men and women to shape the land.[3] Under oppressive conditions, enslaved men and women were forced to clear, drain, and form a six-mile-long canal to secure a navigable path for the transportation of goods and people. One of these canals faces the entrance of the mansion on Somerset Place. When we visited, it was overgrown with vegetation, but one can imagine a time when it flowed freely with small boats and what it would have signaled to a contemporaneous visitor about the Collins’ family control over labor and the Southern landscape (Fig. 2).

Our visit to the Great Dismal Swamp Canal presented an alternative to the colonialist worldview of swamps. The twenty-two-mile canal was important, allowing trade and travel between the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia and the Albemarle Sound in North Carolina, and was similarly hand dug by enslaved laborers (Fig. 3). Past the canal’s edges and deep into the dense vegetation were the sites of once self-sufficient communities of Indigenous and self-emancipated African and African Americans (known as Maroons). In the case of the Great Dismal Swamp, the dense vegetation rendered the wetlands as a place of retreat where escaped enslaved persons shaped a place to live outside the racist capitalist world.[4] Yet, these communities were not completely secluded. As recent archeological surveys of the area reveal, informal markets allowed the trade of goods and resources between Maroons and canal laborers which created a network between these seemingly isolated communities and the outside world.

The last impactful stop on our “swamp tour” is Hobcaw Barony, a large tract of land that was once site to several rice plantations which was then turned into a hunting retreat in the twentieth century. While the location has a history similar to that of other plantations, the interpretation and ecological research that is currently happening at Hobcaw Barony under the auspices of The Belle W. Baruch Foundation brings us to our contemporary moment. The now protected estuary is the site for marine and coastal research that explores the importance of wetlands ecosystems as defenders against rising sea levels, flooding, and other ecological changes due to our current climate crisis. A part of their mission is to bring back the cypress swamps that were once drained for the benefit of few wealthy families. It’s hard not to think of Swamp Thing and Alec Holland who set up a laboratory in the bayou of Louisiana, taking note of the swamp’s ecological importance and its relationship to humanity. During all of these stops, I understood something unique about the Southern landscape, how it was treated, formed, abused, and conserved, and how it informs how we as scholars understand early America. The landscape, just like the past, was not a stagnant place, but was constantly changing, and that the vistas we see know as backdrops of historic sites can often be just as deceitful as the sites themselves.

[1] Based on the comic books by DC Comics of the same name. Created by and illustrated by Len Wein and Bernie Wrightson.

[2] Somerset Place State Historic Site, “Getting to Know Somerset: A Brief History,” YouTube Video, 5:08, May 16, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Ijl8RJkVXU&t=130s.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Daniel O. Sayers, Desolate Place for a Defiant People: The Archaeology of Maroons, Indigenous Americans, and Enslaved Laborers in the Great Dismal Swamp (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2014), 177-187.

Leave a Reply