Fire and Forearms

By Elizabeth Palms, WPAMC Class of 2020

You would not look at my 5’1”, ballet flat-wearing self and imagine me striking a hammer on an anvil with my sleeves rolled up, revealing my highly-toned biceps and sculpted forearms in the glimmer of a furnace light. However, during our Preindustrial Craftsmanship field study trip to Colonial Williamsburg, I got to try my hand at forging an iron S-hook in the armory—sans the highly-toned arm muscles.

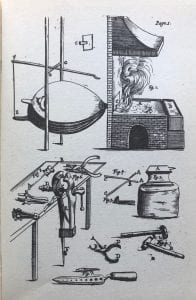

Between the material my first-year classmates and I have been reading for metals block and our Craftsmanship course readings, we have been busy learning all about metallurgy and metal trades. In his famous, Mechanick Exercises: or, the Doctrine of Handy-Works, Joseph Moxon opened his section on “Smithing in General” with a definition, writing, “Smithing is an Art-Manual, by which an irregular Lump (or several Lumps) of Iron, is wrought into an intended shape.” This definition is so simple, but for whatever reason, it sticks with me. There is something satisfying in thinking about the raw materials and about people past and present as makers working with these materials. I digress. Moxon thereafter noted that since this definition “needs no explanation,” he was going to delve right into the particulars of setting up a forge and the specific names and purposes of the trade’s many tools from the hammers and sledges to bellows, vices, all sorts of plyers, and specific parts of the anvil.[1]

A snippet from Moxon’s 1703 Mechanick Exercises illustrating what one might find in a blacksmith’s shop.

Reading about a trade is all well and good, but no matter how deeply I dive into Moxon’s work, Robert Campbell’s 1748 The London Tradesman, R. R. Angerstein’s 1750s Illustrated Travel Diary (one of our class’s favorites), or even secondary literature such as Donald Fennimore’s Iron at Winterthur, nothing could have synthesized things in my mind better than this special opportunity to work iron myself.

My classmate, Emily Whitted in the early stages of forging an S-hook. It was amazing how much our understanding of the trade increased just by feeling the iron and tools in our hands and observing the colors of the different heats.

The most striking—pun fully intended—revelation I had while forging my little S-hook came through the tactile experience of working the metal straight out of the coals. It was remarkable to feel the metal harden with each strike as it cooled. Moxon wrote “of the several Heats Smiths take of their Iron,” gave a basic explanation of red heat, white heat, and sparkling heat.[2] While I found his words instructive, I did not fully appreciate the number and variation of heats that blacksmiths need while forging. Instructing and guiding my classmates and I as we forged our S-hooks was Master Blacksmith, Ken Schwarz, who showed precisely where in the coals to hold the iron bar and what colors to look for in the glowing iron. As I continued to hammer and the iron continued to harden I felt the change in malleability and heard sounds of the hammer against the metal change as well. It was such a treat to get to try my hand at the anvil! It is experiences like this that make us better material culture scholars.

As Mr. Schwarz explained, a skilled blacksmith is able to make so many judgments based on touch, sound, and the nuances in the hot iron’s coloration. All throughout our Craftsmanship class so far, we have found ourselves asking questions regarding how an 18th-century craftsman knew when his or her material was ready, which tool was which, when to stop hammering, cutting, sewing, sawing, planing, burnishing, filing, etc. More often than not, the answer to this question is that the craftsman, after years and years devoted to the trade, just knew. Mr. Schwarz just knows at this point where on the horn of the anvil is optimal for forming the curls at each end of the hook. He just knows what angle to hold the hammer. He just knows, and he and his colleagues in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Trades are keeping this rich tradition of embodied craftsmanship alive.

While I am about as far from being a master blacksmith as possible, I admit, I am proud of my S-hook. It now lives on my coffee table. Making the twist was my favorite part. Photo by the author..

[1] Joseph Moxon, Mechanick Exercises, edited by Charles F. Montgomery (New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc. First published London, 1703), 1.

[2] Ibid., 8-11.

Leave a Reply