Connoising Fenway: Boston’s Jewel Box

By RJ Lara, WPAMC Class of 2019

Major League Baseball parks are my favorite spaces outside of museums and historic houses to use the connoisseurship skills I have been honing over the past year. Amongst the smell of hot dogs and the sound of well-hit baseballs cracking off wood bats, ballparks offer a relaxed and low-stakes setting where I get to take part in two of my favorite pastimes: watching baseball and connoising. With popular baseball culture and the vernacular architecture of MLB parks rooted in the twentieth century, the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and abundance of connoisable tangible objects also offer the opportunity to study material culture from a different time period than what WPAMC fellows typically examine on our field studies. That is why on the Northern Trip I did not miss the opportunity to catch a game at MLB’s oldest ballpark, Fenway Park. With Fenway veteran and baseball savant Greg Landrey (Director of Academic Affairs at Winterthur) by my side, I spent nine innings marveling at the park’s material culture. Here are my two favorite Fenway connoises–that you won’t find on Wikipedia.

- An Entrance for the Masses

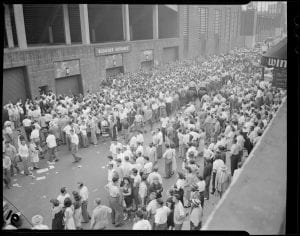

Kids crowding outside the bleachers entrance on Opening Day at Fenway. This is the entrance Greg and I used the night we watched the Boston Red Sox play the Tampa Bay Rays. 1956, photograph courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Forty-five minutes before the start of the game, Greg and I made our way down Lansdowne Street toward the bleacher entrance at Fenway. When we got to Gate C we quickly tucked into the large green doorway and made our way through security just as the evening rain began to pour down. This was unlike my regular ritual of taking my time walking up the stairs to the main concourse on the second level so that the field gradually opened below me. In fact, it was entirely different. As I looked around the ground level, Greg and I were already standing in the main concourse surrounded by concessions and beer stands. There were no temple stairs that opened to the baseball heavens, just steel support beams and concrete grandstands over my head and a sea of people around me holding drink carriers stacked with Fenway Franks. It was a charming moment.

Crowd milling about bleachers entrance at Fenway Park. Greg and I entered through the large door on the far left. ca. 1950, photograph courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Fenway Park is one of two remaining ballparks that have street level entrances and other features contemporary with “Jewel Box” architecture from the golden age of baseball in the early twentieth century, the other being Wrigley Field in Chicago. Jewel Box parks are known for giving the ballpark a more intimate feel. They were intentionally designed to build a community around the team by forming connections from fan to fan, player to player, and fan to player. With street level entrances and concourses at each gate in Fenway (Gate D was later remodeled with outdoor stairs), the masses from all social classes in Boston could flood the gates to grab a box Cracker Jack, relax in the shade beneath the concrete stands, and talk about anything from politics to last night’s game. As one of Greg’s favorite players said about another Jewel Box ballpark, Philadelphia’s Shibe Park/Connie Mack Stadium, “It looked like a ballpark. It smelled like a ballpark. It had a feeling and a heartbeat, a personality that was all baseball.” That charming moment I was experiencing? That was the heartbeat of the Fenway community thumping throughout the architecture.

- Kayem Fenway Frank (with a Sam Adams Boston Lager)

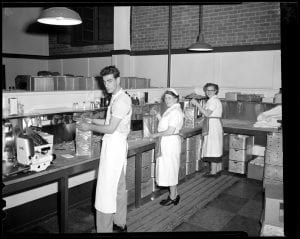

Three unknown ballpark staffers preparing hot dogs in the kitchen at Fenway Park. ca. 1950, photograph courtesy of Boston Public Library.

Foodways are just as important in material culture as they are at the ballpark–perhaps that’s why I indulge in both settings. The indulgence at the top of every ballpark-food connoisseur’s Fenway list is the Fenway Frank. The origin of the term “Fenway Frank” seems to be a mystery, but most agree that it was probably first used around the opening of Fenway in 1912. Many different butchers have supplied the hot dogs for Fenway Franks over the years, and since 2009, Kayem Foods of Chelsea, Massachusetts has held the coveted Fenway Frank crown. It seems to be a match made in baseball heaven as Kayem’s history began just five years prior to the opening of Fenway, and the company’s early efforts focused on the cousin to baseball fans’ favorite food, Polish-style frankfurters.

A Kayem Fenway Frank topped with mustard and ketchup in a split-top New England style hot dog roll. Photograph courtesy of Kayem Foods’ Facebook.

After Greg and I spent some time basking in the beauty of the Jewel Box concourse, we took part in the first step of the Fenway Frank ritual–waiting in the concessions line. Before too long we each had a Fenway Frank in hand, Greg’s topped with mustard and mine with ketchup and mustard. Then something truly special happened. Upon getting barred from finding our seats due to lightning risk, we stood next to the concrete stairs and steel supports and talked baseball as we ate our Fenway Franks, just like the masses have done in the concourse for one hundred and six years. The Fenway Frank had slightly bolder-tasting Polish meats and spices than other hot dogs I have had at ballparks, and the boiled-to-grilled ratio was well-suited to its casing. With the added bonus of eating the Polish-American influenced cuisine on a split-top New England style hot dog roll, dare I say it, it was better than a Dodger Dog.

Boston Red Sox vs. Tampa Bay Rays at Fenway Park on August 17, 2018. Photograph courtesy of author.

It is true, my two favorite Fenway connoises are also the first two I examined. The game had not even started and I was already the happiest fan at the ballpark. In this blog I could have just as easily raved about the entertaining, yet convoluted, social tradition of singing Neil Diamond’s Sweet Caroline in the middle of the eighth inning. I could have swooned over the folklore of Pesky’s Pole, the early-twentieth-century singing of Tessie, and Ted William’s “Lone Red Seat.” I could have broken down Fenway’s stunning layered landscape: the early twentieth century remodel of the Green Monster, the mid-twentieth century addition of the famous Citgo sign, and the twenty-first century additions of the Green Monster Seats and the extended first and third base decks. All speak volumes to the social, cultural, and material identity of Boston from the twentieth century to the present. Those remaining nine innings of the game were remarkable to say the least.

Thanks, Greg!

Leave a Reply