Rats, Paintball, and Breakdancing: Street Art in Bristol

Every January, the first-year fellows of the Winterthur Program and several students in MA and PhD programs from the University of Delaware take part in British Design History: a three-week course on design and material culture with one week at Winterthur and a two-week field study in Great Britain. Traveling to cities including London, Stoke-on-Trent, and Bath, the students have an opportunity to study American Material Culture within a greater global context. Students’ posts in this section are centered on their experiences in England or working with British objects in the Winterthur collection.

Near the end of our time in England, students in the 2018 British Design History course participated in a street art walking tour of Bristol with artist Alex Tamasi. After days of closely examining objects of high design like rich silks and diamond-encrusted snuffboxes at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the handsomely gilded furniture at the Wallace Collection, and the (many!) ceramics produced in Stoke-on-Trent, this was something entirely new.

Banksy’s Well-Hung Lover on Frogmore Street. The work was “tagged” by blue splotches from a paintball gun.

In fact, this was something rather bizarre: instead of looking at pristinely displayed objects within cases under museum lighting, we were outside, looking at stenciled art, the rough textures of buildings, graffiti, and peeling paint. Although the whole experience seemed at first out of sorts with the kinds of sites and objects we had seen, street art, I think, addresses and complicates the questions of design, imitation, and historic preservation undergirding our entire trip.

Two views of Polish artist M-City’s stencil work, 2012. Completed after 22 hours and 55 panels of stencil.

As Alex toured us around Bristol, he encouraged us to see street art not as defacement, but as a layer of the city’s urban fabric. For instance, observing M-City’s monumental work on Nelson Street graphically depicting Bristol’s industrial past allows for an appreciation of the time and careful consideration put into its design, the materials required to produce the image, the physicality of creating the work, and its message. Placed on a building, the artwork visibly represents and points to the underpinnings of its creation and support.

I found myself thinking about how street art occupies an unusual, almost liminal space within Bristol. Street art draws attention to the city’s identity as a palimpsest, literally built up and buttressed by various layers of history, time, artistic and architectural movements, and economic and political moments. By its very nature, street art is never static. Painted over, tagged by others (like in the case of Banksy’s work pictured above), and at times physically demolished along with its building, street art continually transforms and accrues new meaning.

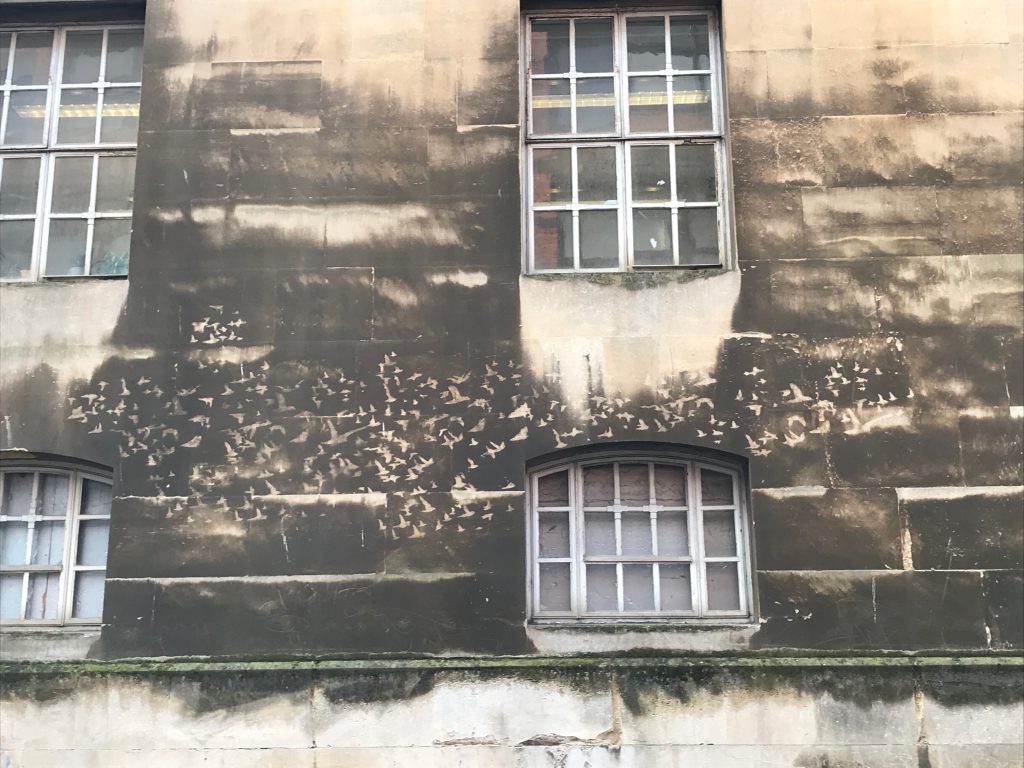

Moose’s “reverse graffiti” on the side of the old police station in Bristol.

My favorite stop on our tour was Bristol’s youth center, which once served as a police station. “Reverse graffiti” covered the walls of the building on which the artist Paul Curtis (known as Moose) used high-pressurized water over a stencil to create a design of birds in flight. Such an image seems to turn our understanding of street art on its head: cleaning, or the removal of layers of dirt, resulted in “graffiti,” or the visible alteration of a public building. Not only does this form of street art circumvent issues of legality (it is not illegal to clean a building!), it more importantly merges architecture, art, cleanliness, and defacement into one palimpsestic entity. Art cleanses, making visible the skin of the building through the lens of contemporary design. The building serves as architectural structure, backdrop, and canvas—it acts as a barrier and a field, as negative and positive space to animate a work of art.

Clothed with the Sun, El Mac. In order to achieve a softer, more painterly effect, El Mac froze his spray paint cans before application. (Note: the light and dark patches are from the sun, not the work itself).

As an art form, street art makes visible the ephemeral and changing landscape of the city. It both draws attention to and obfuscates architecture and history, consolidates “high” and “low” artistic practices, and generates new readings of old forms. Far from the optical lure of diamonds and the enticingly smooth surface of silks, street art is nevertheless a form of design that elevates its vessel and seduces its audiences.

By Kristen Nassif, Ph.D. Candidate in Art History, University of Delaware

Leave a Reply