Lessons in Precision: Harpsichord Making at Colonial Williamsburg

Spanning a ravine, the reconstructed Anthony Hay Cabinetmaking Shop sits atop its original foundations. Unlike the flattened modern terrain of the city, the gully is a surviving remnant of the eighteenth century landscape of Williamsburg, once cut by many similar ravines. The unappealing topography allowed Anthony Hay to purchase two lots on the site for just a bit more than the price of one lot on the main street. He opened the shop in the late 1750’s, producing furniture in the neat and plain style of Tidewater Virginia. The shop subsequently passed to Benjamin Bucktrout, and then Edmund Dickinson, who closed the shop when he went off to join the Continental Army in 1776.

Like many small American businesses in the eighteenth century, Hay diversified, providing funeral services and selling wallpaper, tools, furniture, and coffins. Hay’s shop also advertised the workings of an entirely different trade—harpsichord making. In a 1767 advertisement in the Virginia Gazette, Hay’s successor, Benjamin Bucktrout, proclaimed that the shop also made and repaired spinets and harpsichords.

Virginia Gazette advertisement by Benjamin Bucktrout. January, 1767.

Today, both cabinetmaking and harpsichord making are represented in the Hay shop. Ed Wright, Journeyman Harpsichord Maker, has been making the instruments at Colonial Williamsburg since 1988. While there are two conventional sizes of harpsichords, only the smaller size known as a spinet harpsichord has been made at the Hay shop. Each spinet takes around 800 hours of labor, but customer demand in the eighteenth century would have ensured that a team was working on several of them at once. Upon our visit to the shop, Ed took the class through a small facet of the process—making harpsichord jacks.

Harpsichord jacks in a completed harpsichord. When a key is pressed, it lifts a jack to pluck the string.

The jack is the piece that plucks the string inside of the instrument, a key differentiator from the piano, which utilizes a small hammer to hit the string. The plucking gives harpsichords their crisp sound. When a player presses a key, the back of the key rises and pushes the bottom of the jack upwards. Set into the top of the jack body and mounted on a straight pin pivot, a piece known as the “tongue” holds a carefully angled crow quill in place. The quill plucks the string from the underside, and then pivots back beneath the string resuming a position of rest. While each instrument differs slightly, the spinets that Ed makes have around 61 keys – and therefore 61 jacks – per keyboard.

Harpsichord jacks sitting in their register slots

The production of a harpsichord using eighteenth century techniques depended upon repetition to accelerate the process. In a typical shop, multiple instruments would be crafted at once. While work on a harpsichord ranged from large-scale procedures to the finest of details (such as the jack), many of the separate parts could be made in bulk. This was especially apparent when making jacks, since each one is comprised of many small moving pieces. When making 61 tongues, it made sense to double or triple the production while moving the lot through each step. The repetition of making hundreds of jack parts with specialized tools and jigs improved efficiency and accuracy.

Top: using a jig to accurately punch holes in the tongue of a jack. Middle: a crow’s feather inserted into the punched hole. The feather will be trimmed to size. Bottom: the tongue rotating freely inside the body of the jack.

Despite being able to make the tongues and the jack bodies in bulk, they are only the “blanks.” Each tongue must be fit to the jack body, and then each completed jack must be fit to the slot in the register. The register itself, holding each and every jack in place, is made of 30 separate blocks with carefully sawn grooves. The blocks are assembled by a predetermined measurement to span the width of the keyboard and glued together; all block have to align properly and hold moving parts that slip freely but precisely to pluck the correct string. This kind of precision—where being only 1/16th of an inch off is too much—is rare in most other trades. While not every step of harpsichord making must be quite this precise, such accuracy is required to make the instrument function properly. Many other trades, while certainly capitalizing on the speed and accuracy that come with repetition, do not have to adhere to such a strict margin of error.

The register, comprised of separate blocks (left) and placed in the harpsichord (right).

The harpsichord is a case study for precision and specificity in chosen materials. Makers carefully selected materials for their inherent qualities. Spruce, for the soundboard, was chosen for its resonance. Yellow brass, red brass and iron wires were chosen for their abilities to produce clear tones in certain octave ranges. The jacks were often made of pear wood. This wood possesses a fine and smooth grain, allowing it to slide in and out of the slots of the register without interference. The tongues are made of holly, a tightly grained wood that can handle the pressure of being punched and drilled. The crow quill is stiff enough pluck the string, but flexes to create roundness in the sound. Lastly, the two pieces are held in place by a boar bristle, which has just enough pliancy to act as a spring. With all parts working together, the harpsichord jack is a simple, yet ingenious, piece of technology. It is successful in the precise task that it must perform, which is why the jack did not sustain many changes throughout the harpsicord’s 400 years of popularity.

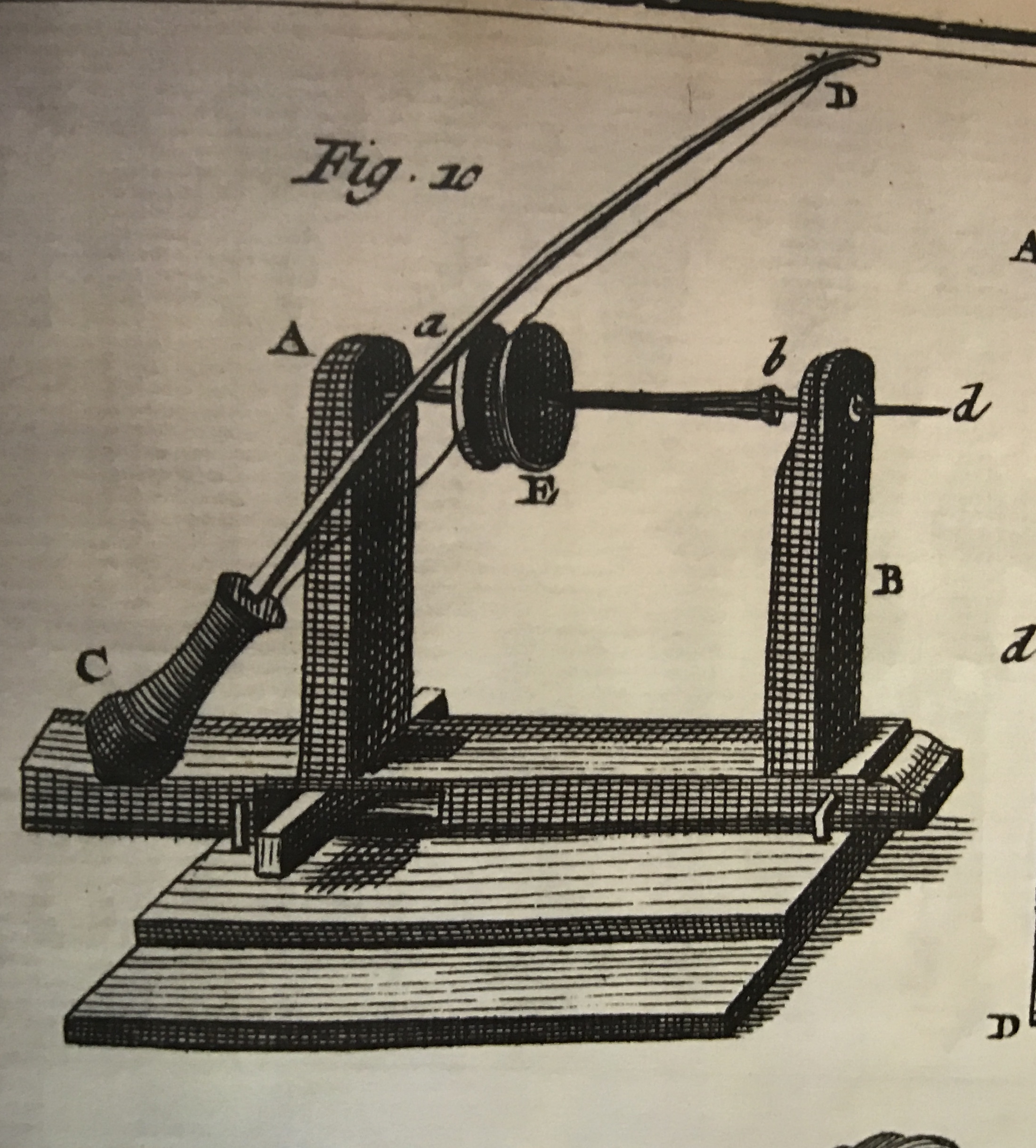

Right: a jewelry drill from Diderot. Left: Ed’s homemade jig drill for the jack body.

Unlike many other trades, which have continuously been practiced since the eighteenth century in both commercial and artistic shops, the harpsichord making ceased in the early nineteenth century when the piano emerged as consumer’s instrument of choice. Ed and his predecessors have had to recreate or reimagine many nuances of the trade to figure out how eighteenth-century harpsichord makers worked—such as using a jeweler’s bit to drill tiny precise holes in the tongue and jack body. Thanks to Ed, our class was enlightened to the complexities of making an instrument—an object that must not only function properly, but also look and sound good while doing it!

WPAMC Fellow Allie Cade (Class of 2018) playing a harpsichord while an apprentice in the harpsichord shop at Colonial Williamsburg. Photo courtesy of Fred Blystone.

.

By Allie Cade, WPAMC Class of 2018

.

For many years, the Department of Historic Trades at Colonial Williamsburg has generously hosted Winterthur students as part of a course in pre-industrial craftsmanship. Over the course of several days, we students work closely with the tradespeople, trying our hands at a wide range of eighteenth century occupations that bring our studies, quite literally, to life. Every year, we leave with a deeper understanding of the material world. This post is part of a series that chronicles our visit in March, 2017.

Leave a Reply