The Mannequin Challenge: A Visit to the John Dickinson Plantation

Overlooking the St. Jones River, Samuel Dickinson’s house rose three stories above the fields before it. Since its construction in 1740, successive generations of the Dickinson family expanded the eight-room, three story house to include a large dining room, plantation office, pantry, and weaving room. A fire in 1804 gutted the east side of the house, so John Dickinson reoriented and raised the roof. I visited this historic site as a part of our Historic Properties class this semester and thoroughly enjoyed its inclusive narrative and the diversity of approaches that the staff uses to captivate their audience.

Exterior of the John Dickinson Plantation, south face

To ground the site’s interpretation, the curators at John Dickinson plantation designed a seasonal furnishing plan to portray the lived experience there. On my visit, the rooms were arranged in their “colder months” display – the seated furniture was uncovered, pole screens stood next to each fireplace, and bed warmers were placed in each bedroom. This plan visually supported the idea that people in the eighteenth century changed the material culture of their home to fit the seasons. Speaking to two guides, I later learned that in the summer months the staff covers the seated furniture and hangs mosquito netting on the beds. This technique brings vibrancy to this historic home.

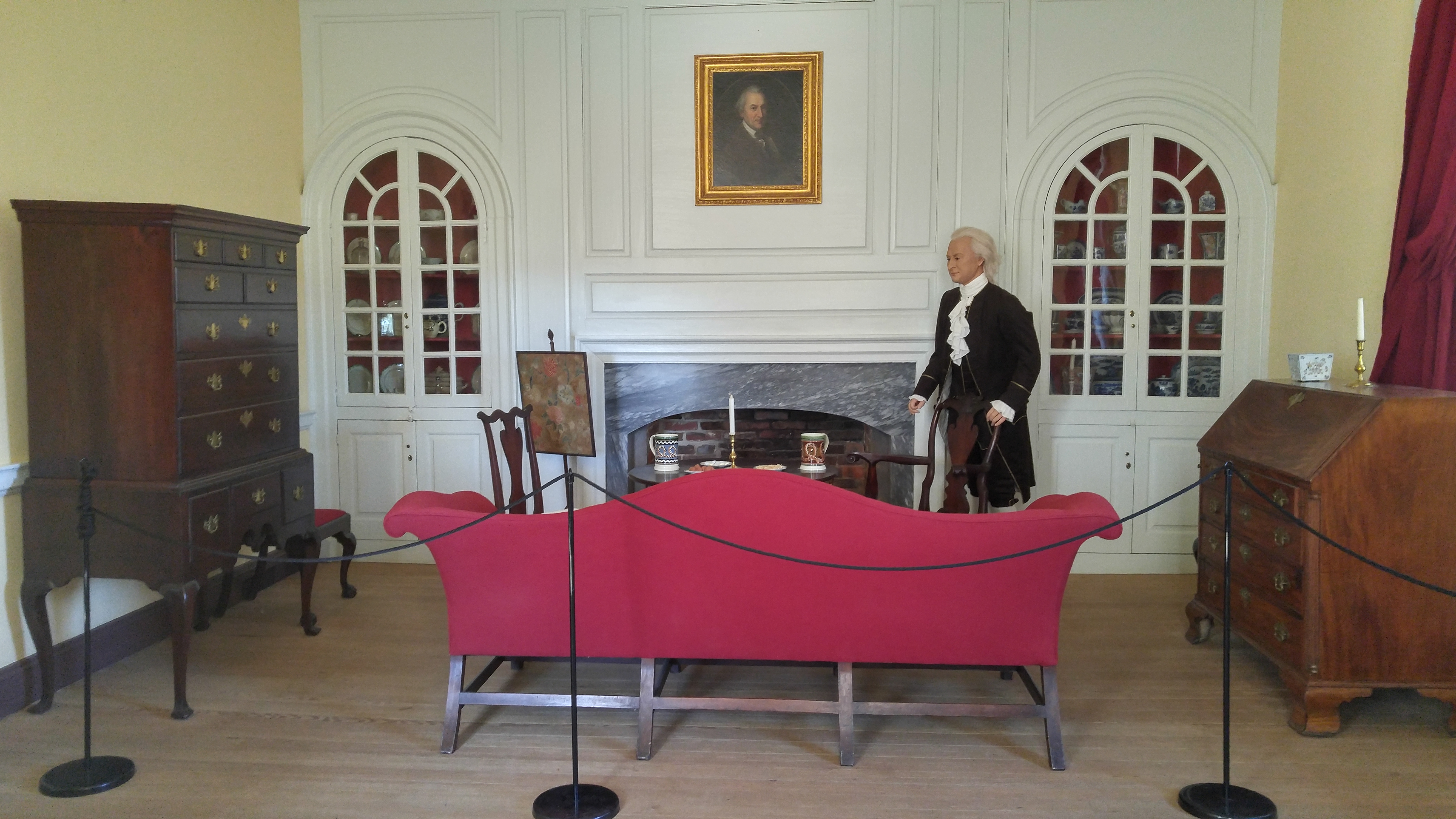

Interior of the “large parlor” – contains family ceramics, mid-18th century furniture, and a mannequin of John Dickinson

As my tour guide noted, Dickinson never left an inventory upon his death, leaving the staff to rely on primary source research and furnishings plans from other historic homes to inform the arrangement. So, to individualize the home, the John Dickinson Plantation features full-size mannequins of four people who lived there – John Dickinson and three enslaved people named Pompey, Violet Brown, and Cato. My guide used these figures to anchor her narratives about who lived in the home.

Interior of master bedroom – contains 18th century furniture and a mannequin of Pompey, an enslaved worker at the Dickinson Plantation

The mannequin of Pompey, seen tending to one of John Dickinson’s wigs, became an anchor for discussions about his role in the house and 18th century fashion. Violet Brown, who served as a caretaker to Dickinson’s eldest daughter, anchored discussions about the experience of childhood at the plantation and the generations of enslaved people who lived there. Cato was Dickinson’s personal servant, so the curators staged him wearing fine clothes. The mannequins gave visitors a visual to latch onto when discussing the lives of enslaved people.

Mannequin of Violet Brown, placed in the room thought to be her own or that of Sally, the younger of the two Dickinson children

Finally, the site used colonial revival as a tool to transport visitors to a different time. Every tour guide on the property wore linen attire inspired by “upper middle class tenant farmers.” Reproductions of late baroque chairs lined the entrance hall for visitors to sit on. The museum is further developing this strategy, creating additional reproductions for visitors to touch. Such an approach will allow tactile and kinetic learners to engage with the information on the tour along with those with a visual or auditory learning style. Paired with minimal narrative in each room to encourage visitors to ask questions about what interests them, my visit to the John Dickinson Plantation was a phenomenal experience!

Colonial revival copies of 18th century chairs for visitors to sit on in the house

By Allison Robinson, WPAMC Class of 2018

Leave a Reply