In Geoffrey Chaucer’s The General Prologue from The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer first explains that he is going to introduce the characters of his story rather than just jump into the story by saying, “But natheles, whyl I have tyme and space/Er that I ferther in this tale pace” (35). By talking directly to the reader and introducing them to his story, Chaucer is showing a consciousness in his writing – a consciousness of himself as a writer. It was not common in Medieval literature for people to refer to themselves as writers, and we can see in The General Prologue that Chaucer is aware of his writing as something to be read by others.

In the prologue, Chaucer goes on to explain the story of a knight who devoted his life to chivalry, truth, and justice (43). We are soon introduced to the knight’s son, who would one day become a knight himself. Chaucer describes the son as having the a strong stature, but most importantly he mentions that the son “coude songes make and wel endyte,/Iuste and eek daunce, and wel purtreye and wryte,/So hote he lovede” (55-57). In other words, he loved to write poetry and songs, draw, dance, and joust. By mentioning poetry, Chaucer is referencing a form of literature in his own poem. This reference exemplifies a form of literary consciousness present by just mentioning the knight’s son’s work.

Another example of literary consciousness appears a bit later on in the prologue, as Chaucer talks about a nun named Madame Englantine who enjoys to sing hymns (125). A Hymn is a song that is usually religious and of praise. Here, Chaucer is conscious of a very specific kind of song and introduces a character it relates to. Not only does Chaucer reference other literature as a whole in this prologue, but he also references religious literature.

Chaucer’s next consciousness of literature appears later in the prologue when he introduces a Monk who could possibly be the next head of his monastery. This man differs from other Monks, for he does not care for anything not modern, especially St. Benedict’s rule that Monks should solely devote themselves to work and prayer. He feels no need to drive himself crazy by reading books and constantly working (186).

In the General Prologue, Chaucer is talking both directly to the audience and referencing other literature in his story. Both represent a literary consciousness, and Chaucer goes on to use literary consciousness in some of his other works.

The Miller’s Tale

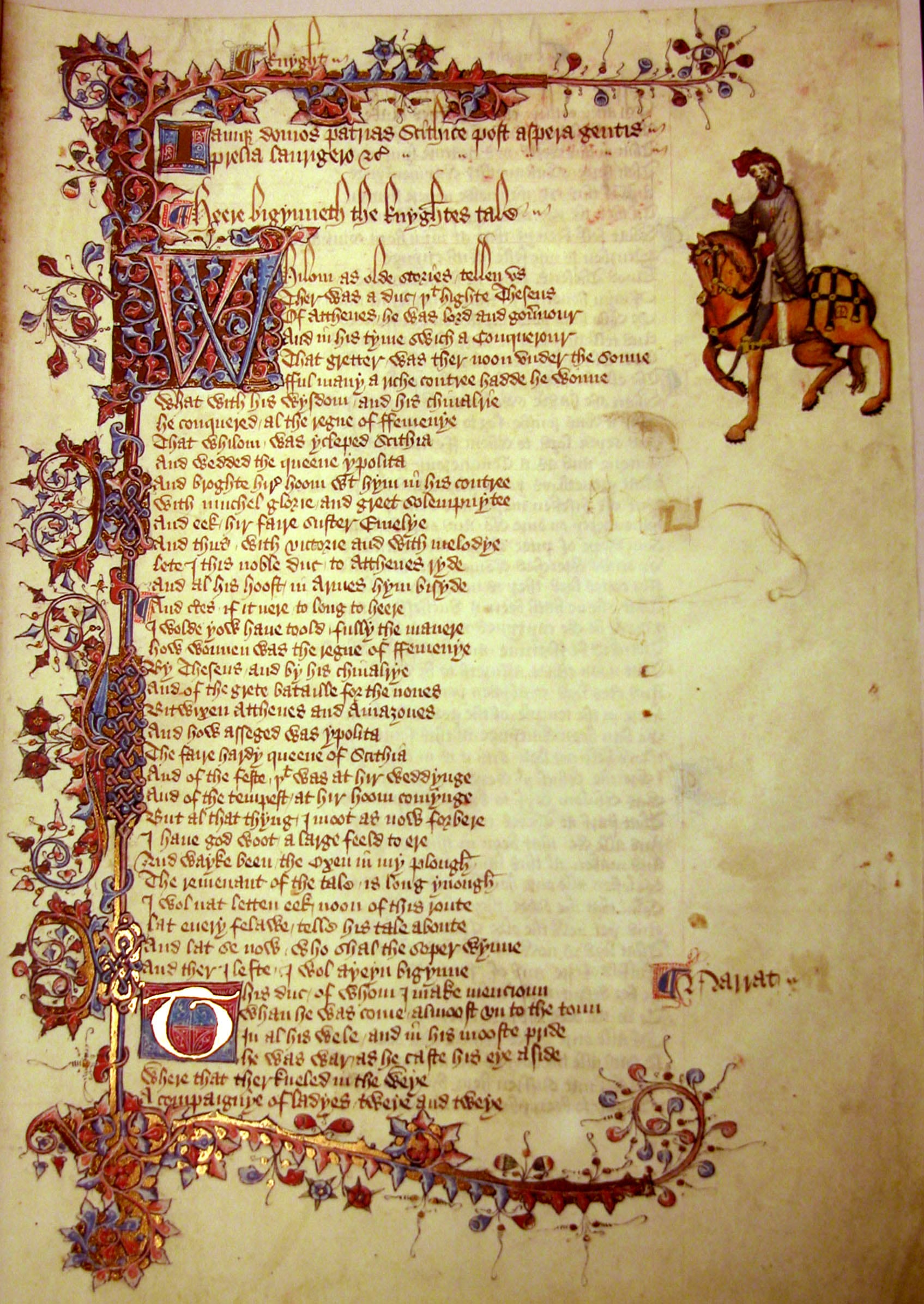

|

| Illustration of the Miller (from http://www.shmoop.com/millers-tale/teaching.html) |

The Miller’s Tale is an interesting one, because although it is called “The Miller’s Tale” no one seems to want to take true ownership of the story. While there are no hints at literary consciousness in the actual tale, it is seen a few times in The Prologue to the tale. Literary Consciousness is expressed through Chaucer and The Miller talking to their audience. Both Chaucer and The Miller try to deflect the blame elsewhere, and although both are somewhat responsible for it neither take outright ownership of the tale.

Chaucer wants the reader to know that the Miller is drunk and he is the one telling the story. He even claims “M’athinketh that I shal reherce it here” (62), saying that even though he will tell the tale he regrets that he will do it. Chaucer knows that this isn’t a family friendly tale, and he apologizes to the reader for that. He goes on to say that if someone does not want to hear such a story they should “turne over the leef, and chese another tale” (69). This seemed to be a very odd tactic to me, because one would think an author would want people to read their story. But perhaps in the time that this was written it was considered inappropriate to write something like this, so Chaucer was just covering himself. At the end of the Prologue to the Miller’s tale he says “aviseth you, and putte me out of blame” (77), claiming once and for all that the reader should not blame him if they do not like the story.

Because Chaucer is so adamant that he is not to be blamed for the story and the fact that it is called “The Miller’s Tale,” the reader might think that the Miller would be responsible for the story. While he does tell the story so he’s responsible in some regard, he too says he shouldn’t be held accountable for the story. Before the Miller even begins to talk the story tells the reader “The Millere, that for dronken was al pale, So that unnethe upon his hors he sat” (13-14), basically saying he was so drunk it was difficult for him to sit on his horse. In these days a horse was the main mode of long distance transportation, so someone must be pretty drunk if they have trouble sitting on their horse. When the Miller begins to tell his tale he first warns his audience “that I am dronke” (30) he realizes he is drunk, as does everyone else, and wants to make it clear. “Therfore if that I misspeke or saye, wite it the ale of Southwerk” (31-32), don’t blame me but the ale if I misspeak or say something wrong. The Miller will go on to tell his tale, but if something comes out wrong he shouldn’t be blamed.

Chaucer was more aware of the vulgar story he was about to tell and the Miller was more concerned with saving face. Chaucer apologizes in advance for what the reader is about to read, and even suggests reading another story if they’re unhappy with this one. On the other hand the Miller just wants to be sure that people know he’s drunk, so if he slips up people won’t blame him but the ale. Both men are aware of what they’re about to do, but in different ways. Chaucer is speaking directly to his audience, the reader, and the Miller is speaking directly to his audience, those present in the story. Both express a literary consciousness that make the story feel as though it is being told to you, instead of you reading it.