|

| The Drury Lane Theatre, London, watercolor by Edward Dayes, 1795 |

Poets are bubbles, by the town drawn in,

Suffered at first some trifling stakes to win:

But what unequal hazards do they run!

Each time they write they venture all they’ve won:

The Squire that’s buttered still, is sure to be undone.

This author, heretofore, has found your favour,

But pleads no merit from his past behaviour.

To build on that might prove a vain presumption,

Should grants to poets made admit resumption,

And in Parnassus he must lose his seat,

If that be found a forfeited estate.

– William Congreve, Prologue to The Way of the World

Background

Before the Stuart dynasty was restored to the throne of England, in 1660, Puritan rule made it very difficult for dramatists to perform. There was little inspiration, and performances were given in secrecy: in taverns or private houses miles from town (Bellinger). During this time period, known as the Commonwealth, theatres were closed. As a result, people were forced to engage in theatrical activities in privacy. Drolls, or a shorter version of plays, quickly became popular because performers could evade some of the restrictions by having “musical entertainments” with friends in their own homes (“Western Theatre: Fix Citation throughoutEnglish Restoration: Theatre Movements“). Charles II was reinstated in 1660. During his years of exile in France, Charles II came to admire the French entertainments and theatrical styles. Upon reaching London, he issued two patents to leading playwrights of the time and performances began once again (Bellinger).

Under the supervision of the Puritans, the theater and creativity had been heavily suppressed. With the onset of the Restoration, however, drama and the arts began to flourish as playwrights and actors alike began taking to the public once again. The latter half of the seventeenth century would see both a reinvigorated sense of bawdy humor as well as the emergence of professional female actresses for the first time in the history of the theater (Victoria and Albert). Scripts and performances reflected on the aristocracy of King Charles II, depicting the members of the upper class as being promiscuous rakes and libertines. Though the style appealed greatly to the audiences for the majority of the Restoration’s duration, from 1700 onwards this type of knavish comedy began to fall out of favor.

Trends

Before the Restoration period, dramatists had to keep all their activities to a minimum. This time period was known as the Commonwealth. During this time, trends in theatre were very secret and personal. William Davenant, Poet Laureate and accomplished playwright, was forced to present his theatrical activity inside of his own home to avoid the censorship of the public theatre. In this fashion he was able to get around all of the restrictions and expectations that were placed on drama during that time. As time went on, trends began to change in theatre. Davenant was finally able to perform his drolls (short plays) in an actual theatre fully equipped with a proscenium arch and wing-and-shutter scenery. Although this was a seemingly minor change, it represented a great victory for the drama enthusiasts of the time. The Restoration period finally allowed dramatists to divorce all prior restraints to their works and create productions that would allow for the emergence of newer and more lively theatrical trends (“English Restoration: Theatre Movements“).

With the start of the Restoration, the theatre and its presence with the public began to flourish. One of the most advanced additions to the stage that emerged during this time was the use of technology both structurally and visually. Inigo Jones was a technology innovator for theatre during the Jacobean period who introduced the concept of moving scenery and the “proscenium arch” to English theatre. John Webb, Jones’ son-in-law, carried on the innovations and brought them into the Restoration period, giving theatre a technological advance (“English Restoration: Theatre Movements“).

Another common trend in theatre during the Restoration period was the reinterpretation of older plays. These were often turned into semi-operas, with singing, dancing, and special effects. Most commonly used were works by Shakespeare (V&A). Davenant in particular took the productions of the past and revitalized them with his newly established and patented theater in 1661. Heading the Duke of York’s Men at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, he sought to bestow his own appreciation of Shakespearean works upon the public by recasting the plays in the picture and preferences of his own society. Performances such as Hamlet, Macbeth, and The Tempest were heavily revised and altered to appeal to the larger audience.

Women as well began to make an appearance in theatre with the advent of the Restoration. Playwrights such as Killigrew and Davenant began casting females for their productions, and the women would go on to meet with good reception from the public audiences. This addition allowed for sexually suggestive scenarios on stage to become even more open and raunchy, a quality that greatly suited the public taste during this time.

Types of Restoration Drama

During the time of the Restoration, 18th century drama was very critical. Much of the Elizabethan Play writers blended tragedy and comedy, whereas the Restoration dramatists chose to separate the two (Nettleton). The drama of this period can be broken into two categories, comedies and tragedies. Restoration tragedy is classified as heroic tragedy. Heroic tragedy is very extraordinary and usually encompasses some extremely good deed done by a very willful, admirable character. Restoration tragedy refers to neoclassical rules making it very imitative. Usually these tragedies are reworkings of Shakespearean plays. There are three types of comedies that were popular during the Restoration. These three types are: Humour, Manners, and Intrigue. Comedies of Humour were made popular by the Renaissance playwright and poet Ben Jonson earlier in the century. These plays centralized around a specific character who had an overshadowing trait. Comedy of Manners were the most popular form of Restoration Drama. These plays would typically mock the upper-class and would usually include vulgar and sexually suggestive language. The third and final form of comedy during the Restoration is the comedy of Intrigue. This type of comedy has a somewhat complicated plot, and usually evolves around romance and adventure (“English Restoration: Theatre Movements”).

Some Restoration Playwrights

William Congreve, often recognized for his excellence and skill in writing comedy, was born in 1670 in Bardsey, West Yorkshire. Congreve stepped into the theater spotlight with his breakout success The Old Bachelor in 1692. Specializing in a more raucous form of promiscuous comedy, he would go on to produce a wide range of successful plays during the final decade of the seventeenth century. His 1697 production, The Mourning Bride, was a change from the otherwise comedic nature of his works. The only tragedy that he would produce during his career, The Mourning Bride met with good reception and would go on to coin several famous phrases, including “Hell hath no fury like a woman’s scorn (“William Congreve”).” Congreve’s career would be short-lived, however, as audience preferences began to shift away from the “comedy of manners” style towards the end of the Restoration. His final play, The Way of the World, was composed in 1700 in response to a particularly vehement critique of his former works. With this comedy, Congreve returned to the early style of the Restoration comedies in an attempt to justify his own prowess, and in the process created one of the best comedies to emerge during the Restoration era (Young).

George Farquhar was another late arrival to the Restoration scene. Born in 1677, Farquhar began writing for the theater in 1698 where he finished his first play, Love and a Bottle, at age 20. His most notable works were The Recruiting Officer and The Beaux’ Stratagem, composed in 1706 and 1707, respectively. The latter was written during the final months of his life at the behest of a close friend, and would go on to become his most renowned play. Farquhar is best known for his roguish humour and rakish characters, as well as his witty dialogue and light atmosphere (NNDB).

William Wycherley was born in 1640 and created plays during the height of the Restoration. His works were best known for their wit and high spirits, as well as lewd undertones and fast plots that audiences of the time desired most. The Country Wife, written in 1675, is a piece that in many ways represents the vast majority of the comedies produced during the Restoration. The play features an overtly sexual pun in its very title, as well as robust language and devious character motives that, while popular at the time, have often prevented it from being performed in a more modern setting (Wycherley).

Popular Theatres

Two patents were issue by Charles II that allowed for two acting companies to be established as the major production companies of their time. Sir William Davenant was granted one of these royal patents and the Duke of York’s Company opened in 1661 (“Western Theatre”). The Duke’s Company originally practiced and performed at The Cockpit Theatre, then Lincoln’s Inn Fields, in Westminster. The company moved to it’s permanent location in 1671 (“Restoration Theatres”). The Doreset Garden Theatre was created and built by Sir Christopher Wren (“Western Theatre”). The patent was later moved, in 1732, to the Covent Garden Theatre in the center of Westminster, London

|

| Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre: Watercolor by George Shepherd, 1811 |

still stands (“Sir William Davenant”).

The second royal patent was issued to Thomas Killigrew, who started the King’s Company. Their theatre, Royal Drury Lane, or Drury Lane Theatre, opened May 7, 1663. The theatre was also created and built by Sir Christopher Wren. After being burnt down by a fire in 1672, Sir Christopher Wren sketched out a new architectural framework and the second Theatre Royal was created. This theatre is still located in the “eastern part of the City of Westminster,” and is “the oldest theatre in London that is still in use” (“Drury Lane Theatre”).

After The Duke’s Company moved out of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, a new theatre was created to take its place. What once was a tennis court became an influential Restoration theatre. In 1695, Thomas Betterton, William Congreve and a few others set up an acting company. They converted the old tennis court into the Lincoln’s Inn Fields Theatre. The company was fairly small and had little resources. When the company failed to flourish, Christoper Rich had a new and proper theatre built in its place. In 1732, Rich’s son finally abandoned the theatre and moved to a new location (“Restoration Theatres”).

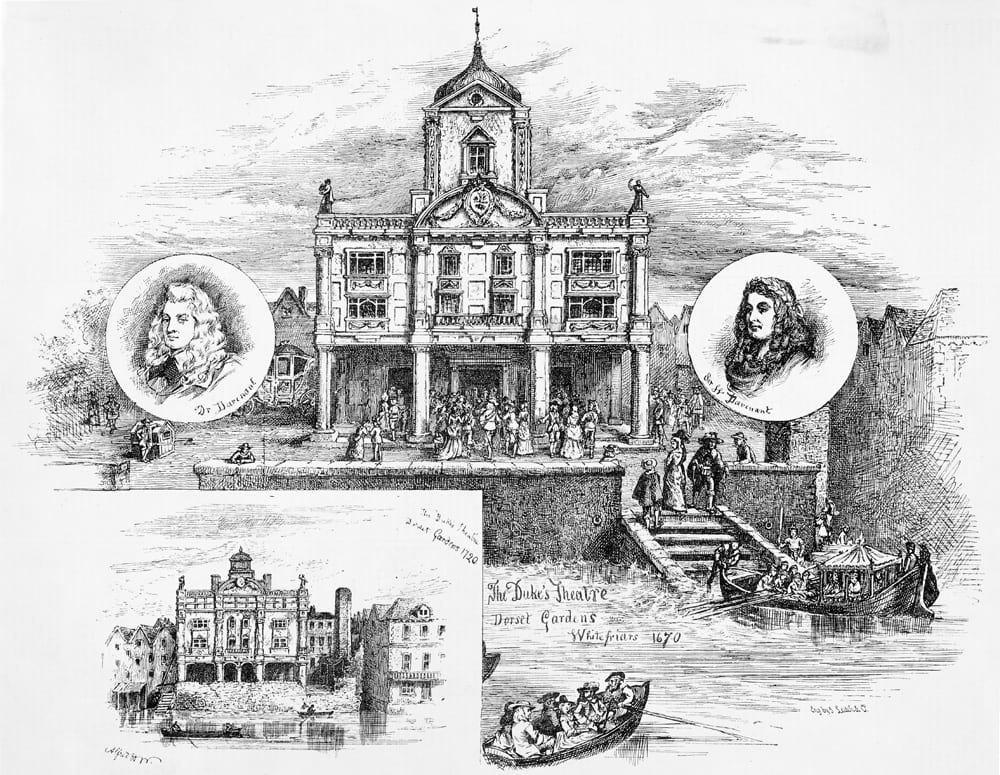

Physical Advancements/Architecture

During the Restoration, semi-operas were rising. The design and architecture of the actual stage, as well as advances in stage machinery, gave way to a flourishing theatrical era in the 1660s. These advances allowed for more elaborate scene and set design, making even transformation scenes possible. The Duke’s Theatre, planned by William Davenant and designed by Christopher Wren. It was built on the Thames river so that viewers would arrive by boat. This was by far the most elaborate theatre Britain had seen during the Restoration period and was also London’s first building to include a proscenium arch (V&A). The proscenium arch framed a scenic stage, a smaller stage attached to the back of the main stage, and used mainly for set pieces. Though the thrust stages of the 16th and 17th centuries were still widely used in the 18th century, they were fast losing popularity to a stage more similar to a modern day one.

|

| The Duke’s Theatre at Dorset Garden (V&A) |

The Decline

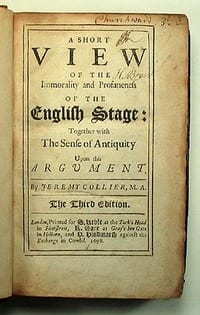

Even though the English broke away from Puritan strictness of the Commonwealth practices, many Protestants still

|

| A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage |

urged society to see the inappropriate and vulgar references in theatre. Different opposers displayed their indignation towards theatre, but one attack truly played a role in the decline of Restoration theatre. Jeremy Collier, a Protestant minister, possessed particularly strong feelings about Restoration theatre. With his belief that theatre should be eradicated, Collier wrote A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage in 1698 (“Western Theatre History”). In this pamphlet, Collier argued three points: the distasteful and bawdy material, the recurrent references to the Bible or biblical characters, and the slander and insults directed towards the clergy. James II issued a formal declaration to attempt to correct issues with Restoration theatre such as immorality and profaneness. Some writers were persecuted and popular actors and actresses were fined. Many dramatists strove to improve the theatre, but little was achieved. The controversy between religious conservatives and dramatists transpired for years. Writers did not seek to reform their works. Instead they approached the laughter, satire, and ridicule as ways to attack their enemies (Bellinger).

References

A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage. N.d. Photograph. Margolis and Moss, Santa Fe. Web. 13 May 2012. <http://www.margolisandmoss.com/shop/margolis/1869.html>.

Bellinger, Martha. “Restoration Drama.” Theatre History. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 May 2012

<http://www.theatrehistory.com/british/restoration_drama_001.html>.

Congreve, William, and Herbert John Davis. The complete plays of William Congreve. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967. Print.

“Drury Lane Theatre”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 6 May. 2012

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/172153/Drury-Lane-Theatre>.

Drury Lane Theatre, London, The. 1795. Photograph. Henry E Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino. Web. 6 May 2012.

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/media/5296/The-Drury-Lane-Theatre-London-watercolour-by-Edward-Dayes-1795>.

Nettleton, George. “English Drama of the Restoration and Eighteenth Century (1642-1780).” (1914): 366. Worldcat. Web. 17 May 2012.

<http://udel.worldcat.org/title/english-drama-of-the-restoration-and-eighteenth-century-1642-1780/oclc/368635/viewport>

NNDB. (2012). Georage Farquhar. <http://www.nndb.com/people/207/000101901/>

“Restoration Theatres.” Western Restoration and 18th Century Studies in English at Western. N.p., 2002. Web. 6 May 2012.

<http://instruct.uwo.ca/english/234e/site/bckgrnds/maps/lndnmprstrtnthtrs.html>.

“Sir William Davenant”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 13 May. 2012

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/152470/Sir-William-Davenant>.

Victoria and Albert Museum. (2012). Restoration Drama. <http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/r/restoration-drama/>

“Western theatre”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 6 May. 2012

<http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/849217/Western-theatre>.

“Western Theatre History.” English Restoration: Theatre Movements. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 May 2012.

<http://westerntheatrehistory.com/EnglishMovements.aspx>

“William Congreve.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Cambridge: University Press, 1910.

<http://www.theatrehistory.com/british/congreve001.html>

Wycherley, W. (2012). Country Wife. <http://www.bibliomania.com/0/6/274/1876/frameset.html>

Young, Mark. (2004, April 13). The way of the world – review.

<http://www.bbc.co.uk/oxford/stage/2004/04/the_way_of_the_world_review.shtml>