|

| George Herbert, Poet |

(George Herbert: a portrait by Robert White in 1674)

“On his deathbed, he sent the manuscript of The Temple to his close friend, Nicholas Ferrar, asking him to publish the poems only if he thought they might do good to ‘any dejected poor soul.'”

Background

George Herbert (1593-1633) comes from a noble family from Montgomery, Wales. Herbert’s father was a wealthy Aristocrat, a member of Parliament who knew many writers and poets such as John Donne. His mother Magdalen later became a patron and friend of John Donne. George’s father died at a young age, and shortly after his father’s death, Herbert’s mother moved him and his six brothers and three sisters to Oxford. Then five years later they moved to London, where they would be properly educated and raised as loyal Angelicans. Herbert began school at age 10, attending Westminster School before moving on to Trinity College. While at Trinity, Herbert earned both his bachelors and masters degrees, and went on to be appointed rhetoric reader at Cambridge. Shortly after becoming a rhetoric reader, Herbert became Cambridge’s public orator, speaking on behalf of the school at a variety of functions. Following in his father’s footsteps, George was elected as a representative to Parliament in both 1624 and 1625.

After leaving Parliament behind, he began his ordination as a deacon supposedly in late 1624. However his life as a deacon gave him a modest income and could not support him. This caused him to live with friends and relatives between 1624 and 1629. His financial condition improved when he became a part owner of land in Worcestershire and sold for a good profit. With his financial gain he was able to focus on his favorite projects, rebuilding churches. During this time he was without a vocation and his poems reflected this period. Poems such as “The Church, “Affliction”, and “Employment” were him reflecting on his progress to find a job that would suit him spiritually and financially.

Herbert had a very complicated relationship with his mother and was only able to communicate with her through his writings. When his mother passed away, he made two huge changes to his life. First, he separated himself from Cambridge, his mothers alma mater. Then he married Jane Danvers on March 5, 1629 after knowing her for three days. What happen to their marriage is unclear but, by the end of 1630 he was ordained priest in Bemerton C. Priesthood for Herbert was not only a spiritual vocation but a social commitment which he explains in The Country Parson. The Country Parson illustrates Herbert’ s conversion from university orator to parish priest. This shows that he had to make changes to his life to be accepted by common country people. This process was strenuous but he had love for the common country life which was detailed in The Country Parson, Whitsunday, Sunday, Lent, and The Elixir.

As a poet, Herbert was not considered as famous as his counterparts. However, he is an important figure because he created an image of religious and political stability in his writing during a difficult period. His poems have a deep religious devotion, linguistic precision, metrical agility, and ingenious use of conceit. His writing of “The Temple” crowned him the name Holy Mr. Herbert.

The 17th century time period had a major influence on Herbert’s work. During this time, there were many battles over religion. People argued over whether or not the Church of England should move towards Protestant churches of Europe or if it should remain a hybrid with Catholic and reformed traditions. These religious ideas influenced Herbert’s writings, and are recognized in his poems “The Flower” and “The Pulley” in which he repeatedly refers to God/The Lord as the creator of all things in nature.

By law everyone in England belong to the Church of England. William Laud was made Archisbishop of Canterbury, he opposed the Puritans who were Protestants who wanted to purify the Church of England from Catholic practices and King Charles agreed with him. Purtians believed that the Church of England was very corrupt and true Christians should removed themselves away from it. Puritans had their own preachers known as lecturers. Laud would try to stop the Purtians from practicing by sending commisoners to make sure everything was in order. Laud emphasized ceremony and decorations in the churches. The Purtians was very against this because they thought that Catholicism would be restored in England. To Herbert he believed Purtians and Catholics were brothers, twin dangers like Scylla and Charybdis between which British church must navigate.(http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/george-herbert)>.

*talk about how he is a metaphysical poet, connect this to analysis*

Herbert is regarded as one of the great metaphysical poets of all-time. Metaphysical poetry is know for it’s use of conceit, which is an extended metaphor that sometimes lasts for the entire piece. Conceit can be seen in both the Herbert writings we’ve analyzed below; Both The Flower and The Pulley themselves are metaphors for something much deeper than their face-value(even though the pulley is not explicitly mentioned in the text. Metaphysical poets are also often seen writing about religion and loves, themes that can be seen in Herbert’s poetry.

(An image of his compiled works: The Temple)

“The Flower”1633

How fresh, oh Lord, how sweet and clean

Are thy returns! even as the flowers in spring;

To which, besides their own demean,

The late-past frosts tributes of pleasure bring.

Grief melts away

Like snow in May,

As if there were no such cold thing.

Who would have thought my shriveled heart

Could have recovered greenness? It was gone

Quite underground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they have blown,

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

These are thy wonders, Lord of power,

Killing and quickening, bringing down to hell

And up to heaven in an hour;

Making a chiming of a passing-bell.

We say amiss

This or that is:

Thy word is all, if we could spell.

Oh that I once past changing were,

Fast in thy Paradise, where no flower can wither!

Many a spring I shoot up fair,

Offering at heaven, growing and groaning thither;

Nor doth my flower

Want a spring shower,

My sins and I joining together.

But while I grow in a straight line,

Still upwards bent, as if heaven were mine own,

Thy anger comes, and I decline:

What frost to that? what pole is not the zone

Where all things burn,

When thou dost turn,

And the least frown of thine is shown?

And now in age I bud again,

After so many deaths I live and write;

I once more smell the dew and rain,

And relish versing. Oh, my only light,

It cannot be

That I am he

On whom thy tempests fell all night.

These are thy wonders, Lord of love,

To make us see we are but flowers that glide;

Which when we once can find and prove,

Thou hast a garden for us where to bide;

Who would be more,

Swelling through store,

Forfeit their Paradise by their pride.

(A cross resting among lilies)

Summary:

“The Flower” was a devotional poem published posthumously in 1633, the year Herbert died, in his collection “The Temple”. The poem takes place through the eyes of a flower that is beginning to bloom in spring, remembering its cold, wilted state in winter, and thanking God for his support and care. In the spring, the flower blooms, all the more beautiful because the desolate winter has just passed. God is the one who lets the plant survive and thrive to blossom in a new spring, and is the one who has protected the flower throughout winter.

This poem, while a pretty and grateful homage to God, is also a deeper poem. The flower is a metaphor for humanity, and the passing of the seasons are the passing of a human life. This can also be related to the Garden of Eden.

Analysis:

| Stanza | Analysis |

| Stanza 1: How fresh, O Lord, how sweet and clean/ Are thy returns! ev’n as the flowers in spring./ To which, besides their own demean/ The late-past frosts tributes of pleasures bring. Grief melts away/Like snow in May/ As if there were no such cold thing. | Here, it is clear what Herbert is saying. The opening stanza is about rejoice. The narrator is praising God for returning spring after a long, late winter. This is an interesting poem because the metaphor always tails the end of the line. Herbert says very plainly what he wants to express. The garden metaphor is woven into his straightforward spirituality. Every other line is a simple praise of God’s world, and the poetic devices are in placed within. The final line “as if there were no such cold thing” can be interpreted to be straightforward or as a part of Herbert’s extended metaphor. |

| Stanza 2: Who would have thought my shrivl’d heart/Could have recover’d greenness? It was gone/Quite under ground; as flowers depart/To see their mother root, when they have blown;/Where they together/All the hard weather/Dead to the world, keep house unknown. |

While this stanza is less orderly in terms of metaphorical placement and organization, it is a more fully involved metaphor. The second stanza is about contemplation. The narrator is in awe of God’s power; even as the flower bud disappears, God gives the root power to return to life in the spring, filled with devotion and God’s strength. Death, and rebirth through God. This may also relate to the sacrament of communion, in which Christians symbolically consume the body and blood of Jesus Christ, who died on the Cross and rose again. |

| Stanza 3: These are thy wonders, Lord of power,/Killing and quickning, bringing down to hell/ And up to heaven in an hour;/Making a chiming of a passing-bell./We say amiss,/ This or that is:/Thy word is all, if we could spell. |

Herbert backtracks here and pauses his metaphor in order to enumerate God’s wonders and his powers. In times of hardship, he is granted spiritual renewal. It happens throughout the seasons, or a man’s life, and each time, the narrator experiences the joy of coming close to God as wholly as the first time. |

| Stanza 4: O that I once past changing were,/Fast in thy Paradise, where no flower can wither!/ Many a spring I shoot up fair,/Off’ring at heav’n, growing and groaning thither:/ Nor doth my flower/Want a spring-shower,/My sins and I joining together: |

The metaphor is extended so that the very weather reflects the mood of the narrator. The first line reflects his rebirth after seemingly being too far from God’s love, and being protected in Paradise, or Eden, or simply God’s love. In the spring of his recovery from sin and hardship, the narrator groans at ‘thither’ or the sinners who have not yet come into their spring. The final three lines can be interpreted as Herbert’s tears of joy. |

| Stanza 5: But while I grow in a straight line,/Still upwards bent, as if heav’n were mine own,/Thy anger comes, and I decline:/What frost to that? what pole is not the zone,/ Where all things burn,/ When thou dost turn,/And the least frown of thine is shown? |

Growing in a straight line may refer to the way flowers grow up towards the sun – this may not necessarily be straight, as Herbert’s spiritual growth may not necessarily be in a straight line. And if God’s anger is a flame, it is like a fire that no winter (or wintry human heart) can face. “what pole is not the zone” refers to not only the geographic placement of the flower, but to the zone of God’s anger. This is interesting, because in literature, oftentimes it is hell, Satan’s domain, that is referred to as being covered with flame and hellfire. |

| Stanza 6: And now in age I bud again,/After so many deaths I live and write;/ I once more smell the dew and rain,/And relish versing: O my only light,/It cannot be/That I am he/On whom thy tempests fell all night. |

This poem is about acknowledging human frailty, and the line “I once more smell the dew and rain” calls to mind the rejuvenation of spring. After rain, the ground smells wet and the plants are nourished. Keeping in consideration that rain may be a metaphor for tears, it is likely that the narrator is rejoicing the cleanse that comes with emotional and spiritual renewal. God is light. “And relish versing” may be a reference to Herbert’s desire to write again, since for him it is a form of prayer. “It cannot be/that I am he” may refer to Herbert’s incredulity –God has restored him to what he once was, and he has a difficult time recognizing himself after the long winter. |

| Stanza 7: These are thy wonders, Lord of love,/To make us see we are but flowers that glide:/Which when we once can find and prove,/Thou hast a garden for us, where to bide./Who would be more,/Swelling through store,/ Forfeit their Paradise by their pride. |

“Store” in the penultimate line may refer to material goods. As a holy man, Herbert doubtlessly disapproves of materialism, particularly when one has devoted themselves to God. Once again, we see that Herbert is praising God for his many feats and abilities and his forgiveness. “Thou hast a garden” refers to the Garden of Eden, completing the poem as an extended metaphor. |

Structure:

“The Flower” is thoughtfully comprised of seven individual stanzas, each with seven lines and a strong rhyme scheme of ABABCCB. These seven stanzas could suggest numerical symbolism. The number seven is said to symbolize an entire period or cycle, which translates over to the idea of perfection and complete order. By structuring his piece in such a way, Herbert is able to further communicate this idea of cycles as they relate to the stages of life and then eventually death. The perfect order of this poem directly mirrors the cycles through which the flower (the human) proceeds through in life. In this poem’s case, the audience follows a “flower” that is reborn out of the ground after a harsh winter to bloom for the upcoming spring season.

Additional cycles are emphasized through the use of the seven stanza, seven line structure, such as the cycle from hell to heaven (being enlightened and saved by God), a passing bell to a chiming bell (death to joy), and Lord of power to Lord of love. Essentially what Herbert is alluding to through his ordered structure is that life has a particular order to it that all humans need to identify. Once they do so, they need to find their own place within that order, which is what our speaker of the poem is able to do by the end of the piece.

Themes:

Christian Refinement: This poem describes the speaker coming out of a time of sin thanks to the graces of God. The speaker uses the metaphor of a flower emerging out of the ground after a harsh winter to reference himself as coming out of a difficult time of sin and grief to once again bloom and have a new chance at life. In this new life, or this new spring in the flower’s case, the speaker will “Grief melts away/ Like snow in May” This melting away of grief shows this process of refinement and the stripping away of sin and dark past for a new life.

Nature: This entire piece utilizes a flower to represent all of humanity. During the winter months, a flower buries itself in the soil, essentially getting closer to “hell” to protect itself from the harsh conditions. In preparation for this time, their petals or “hearts” shrivel and they lose their beautiful greenness. This directly mirrors humans when they go through time of sin or when they stray away from the guidance of God. They become closer to hell and require a time of rebirth. It is not until the beautiful spring that the flower is able to be reborn again, “sweet and clean” and are able to stretch up to heaven. Similar to the flower blooming in the spring, when a human looks to God again for guidance they are essentially reborn from this time of sin.

The Pulley:

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by,

“Let us,” said he, “pour on him all we can.

Let the world’s riches, which dispersèd lie,

Contract into a span.”

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honour, pleasure.

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that, alone of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

“For if I should,” said he,

“Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature;

So both should losers be.

“Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness;

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.”

Summary:

The Pulley was also published in Herbert’s 1633 collection The Temple. The piece takes place in the moment God is creating mankind, and features dialogue by God Himself. The poem is formatted into 4 stanzas, each containing 5 lines with an ABABA rhyme scheme. As he does in many of his other works, we find Herbert pondering Christian ideas and topics: the creation of humanity, God’s generosity etc. The Pulley differs from other poems written by Herbert in that it was not a deeply emotional or personal poem, but rather almost neutral and informative in it’s tone. The title, The Pulley, has been interpreted as being a symbol for mankind being pulled closer to God.

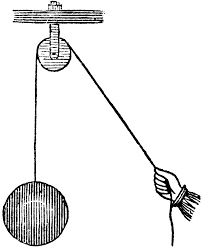

(A Pulley – does not convey the metaphorical complexity of the poem, but serves as a contextual example of what a pulley is.)

Analysis:

| Stanza | Analysis |

| Stanza 1: | Herbert places the reader in a place that no man has ever physically been: God’s creation of man and the world. This sets the tone for the poem to be taken less literally and more metaphorically, but also raises the intriguing question of who God is speaking to. One could argue the quotations were added arbitrarily; however the dialogue certainly adds a personal element to the poem, making it seem like God is talking to the reader as there is no one else mentioned. This conversational-style adds ethos to the poem, seeming to suggest to readers that this could be the word of God. Herbert introduces the concept of God metaphorically “pouring” blessings on all of mankind, with God showing readers his generosity (a reoccurring theme in the Bible) stating, “…pour on him all we can. Let the world’s riches..contract into a span.”. |

| Stanza 2: | In this stanza, Herbert lists the blessings with which God bestows upon humanity: strength, wisdom, to name a few. It’s interesting how the blessings Herbert chooses are not physical commodities, like food or shelter, but rather on things we might take for granted as simply human traits. In doing this, Herbert is reminding readers that God’s love is much more important with worldly possessions. In its third line, Stanza 2 (and arguably the whole poem) takes a turn. God goes from generous and wanting to give us everything to suddenly reluctant to bless us with one more quality: rest. Herbert tells us that this is the only thing God chooses not to gift us, “…alone of all his treasure, Rest in the bottom lay.”. |

| Stanza 3: | God explains His reasoning for withholding rest from man. He contends that if He were to give us rest, man would only love God for his “gifts” (the previously mentioned character traits), and would grow content and lazy in their worship, “…rest in Nature, not the God of Nature.”. Like Stanza 1, this stanza draws on some Biblical concepts, such as man’s creation in the image of God in The Book of Genesis (“…my creature”) and the Christian God being a jealous one, as He declares in the story of the golden calf in The Book of Exodus. He ends the stanza by concluding that with this lack of worship, both He and His people are doomed. God continues His thought from Stanza 3 into Stanza 4, indicated by the quotation marks being left open at the end of the line. |

| Stanza 4: | Herbert continues God’s thought with an initially-deceiving play on words. God says, ” Yet let him keep the rest”, making the reader pause for a second and anticipate God blessing us one last time. Instead of blessing us with rest itself, Herbert has God give us “repining restlessness”. God goes on to explain Himself, saying He is allowing man to have many blessings if they work hard,”Let hime be rich and weary…”. God finishes by saying, “If goodness lead him not, yet weariness may toss him into my breast.”, meaning that this lack of rest is beneficial to humanity because if they are not drawn to God for his good works, they will come to him still to find the rest and inner-peace that eludes them on Earth. Herbert portrays God as a warm and inviting place to go to solve one’s troubles in the final line, “…toss him into my breasts” paints God as a protector and safe haven, with “toss” carrying the sense of excitement and longing that a weary person must feel when they find God, and God’s breast representing the warmth and safety one can find in God. |

Themes:

God’s boundless love/generosity::

God begins the poem by showering His people with blessings and spreading them across the span of the world for all to enjoy. Then, He is portrayed as a comforting place to turn in times of distress in the last stanza. Herbert most likely wanted to emphasize this all-loving quality the most, as this is one of the central teachings in the Christian faith. Lastly, God’s wisdom is on display here as he withholds what He must know to be the detrimental blessing of rest, showing that He and He alone knows what’s truly best.

Man’s Love for God:

The poem conveys a sense that man’s love for God is almost required for survival. God is the one giving and withholding all of these blessings. Also, God warns humanity about the danger of loving all that He has given them over Him. Man’s love for God must be committed and true for them to ever know rest. The poems title could represent God pulling man up to him into the heavens, therefore He is bringing the ones He made in His image closer to Him.

References

Cross and Flower. N.d. Web. <http://duowallpaper.com/cross-and-flowers/>.

“George Herbert Biography.” Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.biography.com/people/george-herbert-9336045>.

“George Herbert.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/george-herbert>.

“George Herbert.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets, n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/george-herbert>.

“George Herbert-Biography.” George Herbert-Biography. N.p., 2007. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.georgeherbert.org/life/bio.html>.

“George Herbert – The Flower.” Genius. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://genius.com/George-herbert-the-flower-annotated>.

Herbert, George. “The Flower.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, 1633. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/181059>.

Herbert, George. “The Pulley.” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, 1633. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/173635>.

Johnson, Anninna. “The Life of George Herbert.” The Life of George Herbert. N.p., 1998. Web. 11 Dec. 2015. <http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/herbert/herbbio.htm>.

“The Language of Man and the Language of God in George Herbert’s Religious Poetr.” (2003): n. pag. Digital Commons. Web. <http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=etd>.

The Pulley By George Herbert. Perf. David Hart. N.p., 2010. Web. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGFpUwpHU_E>.

Ray, Robert H. A George Herbert Companion. New York: Garland Pub., 1995. 83-84. Print.

The Temple Page Edition. 1633. Web. <http://www.georgeherbert.org.uk/Herbert/Works/>.

White, Robert. George Herbert Portrait. 1674. National Portrait Gallery, London. Web. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Herbert>.