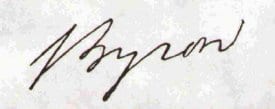

Lord Byron, 1814.

Byron’s Don Juan and Romanticism

By contrasting the characteristics of Augustan and Romanticism poetry, it becomes possible to better understand the major poetry of these adjacent movements. Such is the case with Lord Byron’s poem Don Juan. Begun in 1818, Don Juan’s 17 cantos remained unfinished by Byron’s death in 1824. Unlike the legendary Don Juan, known for his philandering, Byron’s Don Juan is about a man who is seduced by women.

While it is clear from his other works and the time during which he was active that Byron was a Romantic, Don Juan contains elements from the previous literary period. The narrative form of Don Juan as a variation on the epic form, or mock-epic, reminds us of Augustan works, such as Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock. Not only are the events and characters of the poem infused with satire and humor reminiscent of Augustan Age, but Byron also praises Augustan poets and downplays noteworthy poets of the Romanticism. For example, he writes, “Thou shalt believe in Milton, Dryden, Pope;/Thou shalt not set up Wordsworth, Coleridge, Southey;/Because the first is crazed beyond all hope,/The second drunk, the third so quaint and mouthy:” (ll.1633-1636). The criticism of other rival writers, as seen here, was a common trope of the Augustan period. Don Juan should be viewed as a statement of Byron’s perspective on the state of Romantic poetry as well as a piece that combines Augustan and Romantic characteristics.

For more information on the Augustan Age and Romanticism, click here.

Presented below are excerpts from Don Juan that contain Augustan characteristics, such as satire, irony, comedy, and empiricism (the theory that true knowledge come through the senses rather than reason). The poem satirically mirrors Augustan ideals while also representing Romanticism with the emphasis on the role of the poet, ordinary subjects, and the prominence of emotion.

|

| Byron’s signature |

Satire and Irony

Canto 12, 29

In one point only were you settled — and

You had reason; ‘t was that a young child of grace,

As beautiful as her own native land,

And far away, the last bud of her race,

Howe’er our friend Don Juan might command

Himself for five, four, three, or two years’ space,

Would be much better taught beneath the eye

Of peeresses whose follies had run dry.

Canto 12, 70

Though travell’d, I have never had the luck to

Trace up those shuffling negroes, Nile or Niger,

To that impracticable place, Timbuctoo,

Where Geography finds no one to oblige her

With such a chart as may be safely stuck to —

For Europe ploughs in Afric like “bos piger:”

But if I had been at Timbuctoo, there

No doubt I should be told that black is fair.

Canto 8, 70

Koutousow, he who afterward beat back

(With some assistance from the frost and snow)

Napoleon on his bold and bloody track,

It happen’d was himself beat back just now;

He was a jolly fellow, and could crack

His jest alike in face of friend or foe,

Though life, and death, and victory were at stake;

But here it seem’d his jokes had ceased to take:

Comedy

Canto 15, 8

O Death! thou dunnest of all duns! thou daily

Knockest at doors, at first with modest tap,

Like a meek tradesman when, approaching palely,

Some splendid debtor he would take by sap:

But oft denied, as patience ‘gins to fail, he

Advances with exasperated rap,

And (if let in) insists, in terms unhandsome,

On ready money, or “a draft on Ransom.”

Canto 15, 12

His manner was perhaps the more seductive,

Because he ne’er seem’d anxious to seduce;

Nothing affected, studied, or constructive

Of coxcombry or conquest: no abuse

Of his attractions marr’d the fair perspective,

To indicate a Cupidon broke loose,

And seem to say, “Resist us if you can” —

Which makes a dandy while it spoils a man.

Empiricism

Canto 15, 87 and 88

Also observe, that, like the great

Lord Coke (See Littleton), whene’er I have express’d

Opinions two, which at first sight may look

Twin opposites, the second is the best.

Perhaps I have a third, too, in a nook,

Or none at all — which seems a sorry jest:

But if a writer should be quite consistent,

How could he possibly show things existent?

If people contradict themselves, can I

Help contradicting them, and every body,

Even my veracious self? —

But that’s a lie: I never did so, never will — how should I?

He who doubts all things nothing can deny:

Truth’s fountains may be clear — her streams are muddy,

And cut through such canals of contradiction,

That she must often navigate o’er fiction.

References

Diakonova, Nina. Byron’s Prose and Byron’s Poetry. Rice University, 1976.

Don Juan. http://www.archive.org/stream/workslordbyron10unkngoog/workslordbyron10unkngoog_djvu.txt

“Lord Byron, 1814.” http://www.artflakes.com/en/products/lord-byron-after-a-portrait-painted-by-thomas-phillips-in-1814