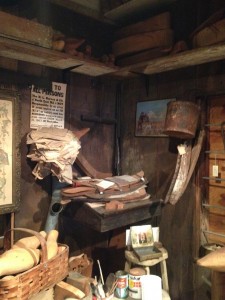

Standing inside the Decoy Shop at the Upper Bay Museum in North East, Maryland, in late January, I could not decide where to start our Museum Studies SWAT team Decoy Shop project.

Should we work from top to bottom, or should we tackle one corner at a time? At the suggestion of one of my colleagues, we carefully plucked a wooden duck decoy from a worktable and started with artifacts displayed on that surface. Our eight day project to inventory, clean, photograph, and catalogue the period room–or a museum exhibit room created to evoke a specific time and place–at the Upper Bay Museum had begun. (Other SWAT team members catalogued the other collections displayed throughout the Museum.)

What can we learn from the Upper Bay Museum Decoy Shop period room?

University of Delaware Museum Studies Director Kasey Grier examines decoys at the Upper Bay Museum prior to the begin in of the SWAT project

The Decoy Shop at the Upper Bay Museum is an installation curated by Upper Chesapeake Bay residents who make decoys, or imitations of ducks or other animals hunters have used to lure their prey at least since 400 BC, and who hunt and fish in the region known as the Susquehanna Flats in the Upper Chesapeake Bay.

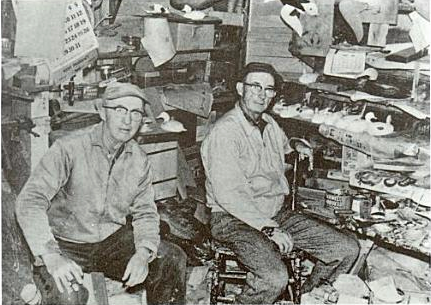

Unlike many period rooms, though, the Shop interior was not copied directly from archival documentation or taken in its entirety from an original shop. Rather, the shop is a conglomeration of decoy-making related objects from several makers. Museum curators likely drew inspiration from a variety of sources, including twentieth-century interior photographs of other decoy shops in the region as well as the personal experiences Museum curators and local practitioners have had with decoy carving.

Steve and Lem Ward inside a decoy carving shop around 1918

(From Joe Engers, ed., The Great Book of Wildfowl Decoys, 2000)

Upper Bay Museum curators arranged the artifacts to evoke the interior of a working mid twentieth-century decoy maker’s shop on the Upper Chesapeake at the tale end the height of market duck hunting but during the continuation of sport duck hunting. This interpretive choice offers a different type of historical authenticity than do other methods of creating period rooms (no single method of which I find “right” or “wrong”–all are all fascinating and informative).

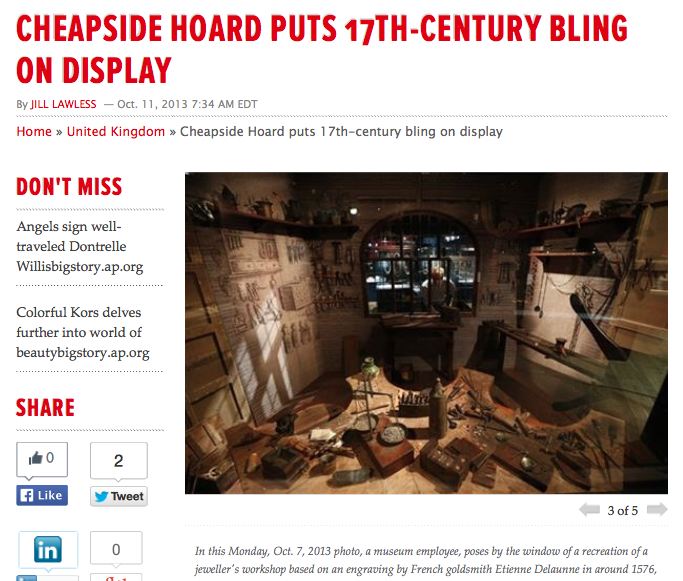

The Decoy Shop is unique in that it is one of only a handful of workshop period rooms in American museums. (In contrast, countless domestic period rooms–championed in the early twentieth century by institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York–fill museums throughout the country.) Others workshop period rooms include a Decoy Shop exhibit at the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum, the Dominy Shops (furniture and clockmaking) at the Winterthur Museum, and the Wright Cycle Shop at Greenfield Village. European examples include a recreation of a sixteenth-century jeweler’s workshop, based on a 1576 engraving, on display in the Museum of London’s show about the Cheapside Hoard.

The Upper Bay Museum and its collections embody rich interpretative value relating to the interconnectedness of the region’s cultural and environmental history. To that end, the Museum’s Decoy Shop period room plays a unique didactic role that could not be achieved by a traditional gallery display featuring rows of workbenches and tools. Instead, by furnishing the Decoy Shop with a variety of objects associated with the craft and related industries, the period room display provides visitors with an opportunity to explore the relationships between decoy-making tools, decoy parts, the spaces and places where decoys were made, and the people who made them, as determined by Upper Chesapeake individuals with ties to the profession and hobby of decoy carving and duck hunting.

Visitors view the Shop interior from one vantage point behind a door or from behind the Shop’s two windows. There is plenty to see. The shop is filled with hundreds of objects associated with decoy carving as well as with hunting, fishing, and boating in the upper Chesapeake more generally. The objects are displayed on shelves, on the walls, and on the floor. Objects range from workbenches to piles of nails. Primary object groups include: large pieces of work furniture; containers filled with supplies and tools; hand tools such as files and spoke shaves; completed decoys as well as decoys in various states of completion; a few items associated with the H. L. Harvey Company (active from about 1880 to the mid twentieth century); and miscellaneous items associated with fishing and hunting such as a life preservers and boat parts. In addition, the Shop “complex” also includes two workbenches installed just outside the shop.

Museum Studies Staff Assistant Tracy Jentzsch vacuuming an early twentieth-century life vest at the Upper Bay Museum

In the process or leading the group that documented and catalogued the shop contents, it occurred to me that, even though we carefully removed and replaced each artifact, the Shop looked slightly different–a bit more tidy and spruced-up–when we were through with our work (before photo at left; after photo at right). We did, after all, dust every object and display surface; vacuum using a HEPA vac; sweep; wash the windows; secure objects using cotton twill tape where there had been duct tape…and more (all of which will help ensure the longer-term preservation of the objects). Even these slight, non-interpretative changes made the shop look different. What are the effects of more evasive interpretation changes on period rooms? How does one strike an appropriate balance of preservation and work-room-like authenticity?

In the case of the Decoy Shop at the Upper Bay Museum, authenticity derives from workshop dirt, the objects’ provenance (or history of ownership and use), and the identities of those who put them there. The Shop contents were made and used by several Upper Bay decoy carvers, a layered history that highlights continuities and change over time as it relates to decoy carving in this region. Some upper Bay decoy carvers represented here include Standley Evans (1887-1979; active 1919-1933) (used the decoy horse inside the shop); Horace D. Graham (1893-1982; active 1955-1978) (used the auto-sander inside the shop and shaving bench outside the shop as well as the many miscellaneous workshop contents distributed throughout the shop), and Paul Gibson (1902-1985; active 1915-1985) (used the painting table and paint brushes on display).

Despite the fact that hunting waterfowl in the Upper Chesapeake was limited to sport (rather than market hunting) after 1918, decoy carvers—such as those represented inside this Shop—continued to provide decoys for sportsmen into the mid-twentieth century. Some of the decoy carvers represented inside the Shop were hobbyists; others made decoys for a living. All of them used store-bought tools in combination with handmade tools made using a mix of reused and new materials, suggesting the fact that many decoy carvers engaged with (and continue to engage with) their craft as skilled do-it-yourself artisans or tinkerers. For example, the Horace Graham auto-sander was made with used wood and a washing machine motor:

His shaving bench features repurposed moldings:

Many of the supply containers were made from recycled mid-twentieth-century food containers, examples of which can be seen lining the Shop shelves in the photograph below. Anyone who has ventured inside a contemporary workshop has probably seen similar examples of reuse.

And of course, there are the decoys. The unfinished duck decoy parts, some of which are displayed inside this basket, were made by the following individuals, several of whom are still living: Mike Laird, J.E. Gonce, Bill Streaker, Jeff Muller, Vernon S. Bryant, Joey Jacobs[?], James Frey, and Bobby Simons:

Hardly a static exhibit meant to evoke one time period, the Decoy Shop at the Upper Bay Museum embodies the continued local interest in and practice of the craft of decoy making.

What could be more authentic than that?

To learn more about how your museum can apply to the UD Museum Studies SWAT project, visit the Sustaining Places web site. This blog post has been cross-posted at the University of Delaware Museum Studies blog.

In preparing for my work at the Upper Bay Museum, I found that C. John Sullivan’s Waterfowling on the Chesapeake, 1819-1936 (2003) provides readers with the best historical context for duck decoy use. Those with a theoretical bent might enjoy Marjolein Efting Dijkstra’s The Animal Substitute: An Ethnological Perspective on the Origin of Image-Making and Art (2010).

About the author: Nicole Belolan is a Ph.D. Candidate in the History of American Civilization program at the University of Delaware. She is also a graduate assistant for Sustaining Places, an IMLS-funded initiative that is dedicated to providing hands-on, practical resources for small museums.