The Cover Judges You; Don’t Judge by the Cover

In the Book Connoisseurship block, fellows learn to study the materiality of books, looking deeper than the informational content to read books as objects. For my block assignment, I was immediately drawn in by a cover featuring a print of an angry looking woman bashing rum bottle cannon. Taking my cues from the cover, I prepared to write about print culture in the late 19th century temperance movement.

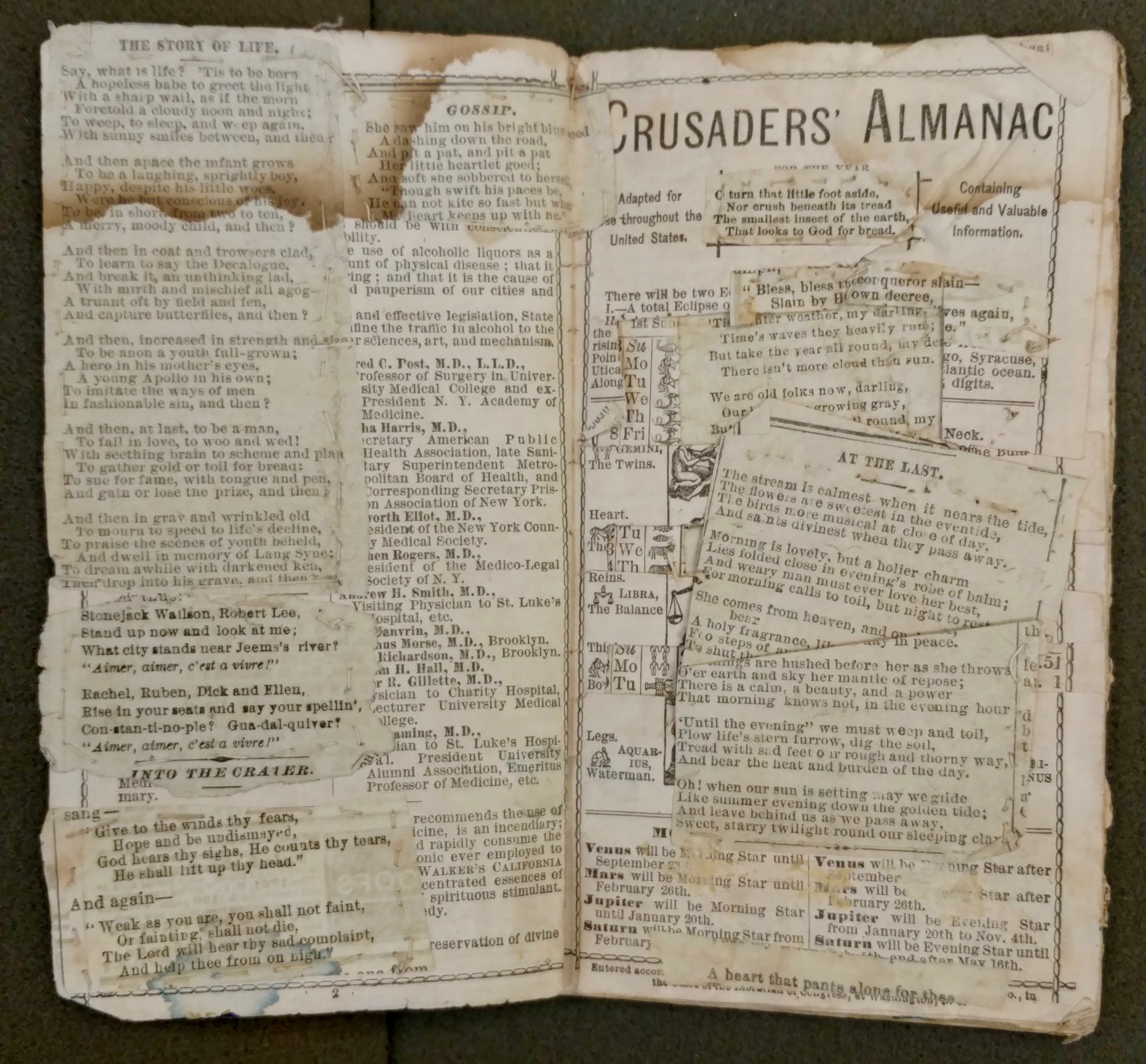

Figure 1 The front cover certainly got my attention, but obscured this book’s most important function as a scrapbook. All images from Crusade Almanac, (New York: R. H. McDonald & Co., 1875.) Unprocessed collection of Winterthur Museum and Library Rare Books, Donation of Saul Zalesch. Photos by the author

But don’t judge a book by its cover! When I sat down to look closely at this object, I was surprised to find the pamphlet radically altered from its original state: the owner had used this publication as the basis for a scrapbook, covering up the content on most pages with pasted-in newspaper clippings. These significant marks of ownership were the real story I wanted to explore.

On most pages, the original published content is completely obscured by clippings.

Unfortunately for me, the anonymous scrapbook creator chose articles that were widely published in newspapers across the country, generally romantically-themed poetry and humorous riddles. There were no inscriptions or marginalia to help identify an owner.

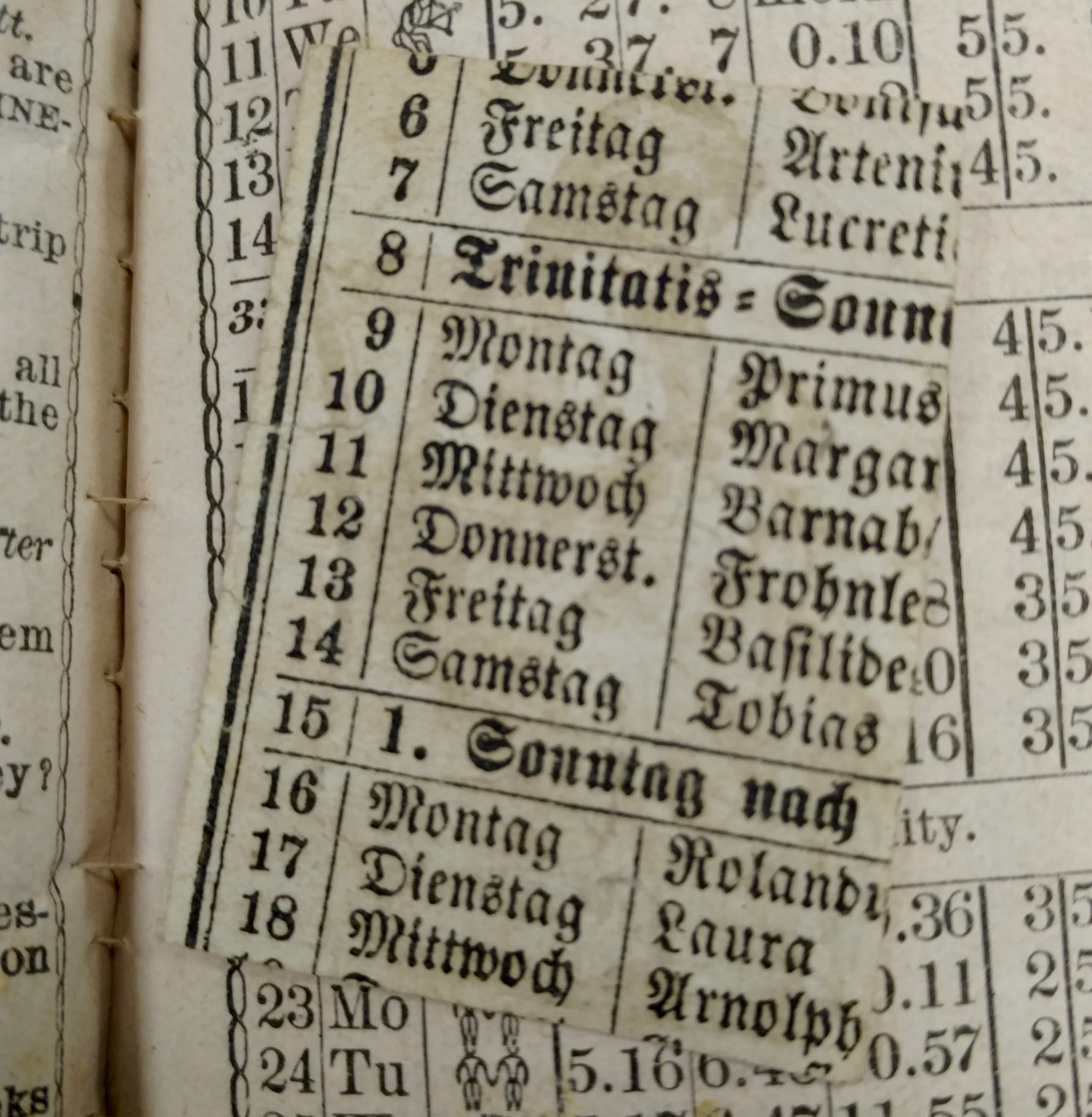

Two small clues, however, began to chip away at the anonymity. First, a clipped poem advertising a clock shop mentions the distinctive name “Zumbush”—this likely refers to Zumbush’s clock shop, operating in the 1870s and 1880s in Indianapolis. Secondly, the verso of a small inclusion bears German text that appears to be taken from another almanac. If the scrapbook’s creator had access to German language publications, he or (probably) she may have been part of the large German population that settled in the Midwest by the turn of the century.

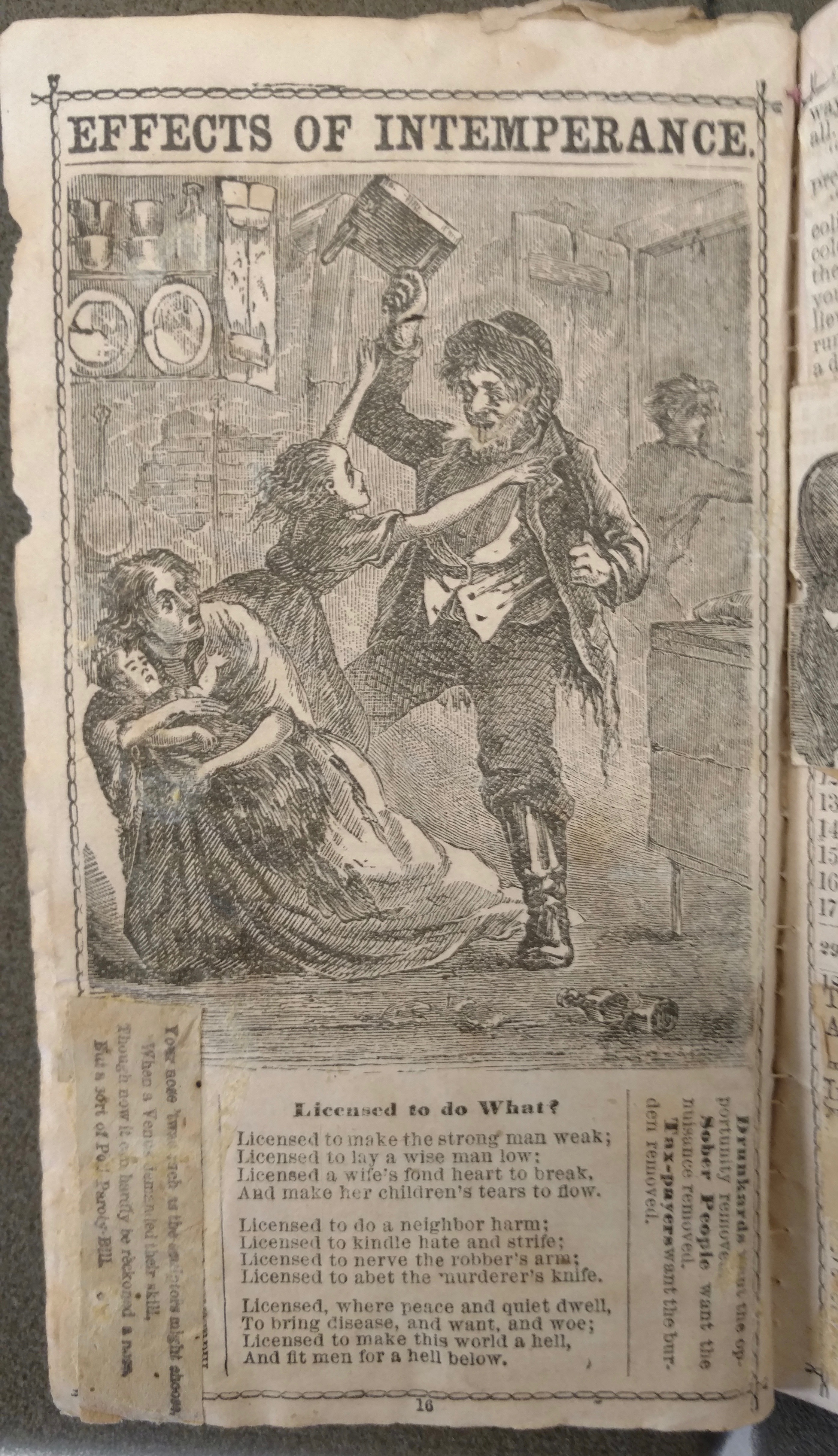

Of course, I couldn’t totally ignore temperance in studying this publication. These almanacs were published by R. H. McDonald and Company, producers of non-alcoholic medicinal bitters. They were distributed free of charge to customers, and advertised the company’s products using pro-temperance propaganda while providing useful reference information typical of general almanacs. The owner of this particular volume did leave a few aspects of the original content unobscured by clippings, in all cases choosing to keep material that directly promoted the temperance movement. Most significantly, the dramatic prints featured on the front and back covers are left untouched.

Today, this almanac survives as a one-of-a-kind creation, a fascinating testament to the power of the temperance movement in popular culture, and to how marks of ownership transform printed sources. Though other copies of the 1875 almanac survive, none can tell the story that this copy does, which puts the temperance movement into the context of the larger, thematic world of print culture consumed by readers of the late nineteenth century.

By Candice Roland Candeto, WPAMC Class of 2018

Leave a Reply