The Wig Makers: Teaching the Historic Trades

Master Betty Myers and journeywoman Debbie Turpin operated the Peruke and Wig Maker’s shop when we visited. In the late eighteenth century, it was one of several similar businesses in Williamsburg. Owned originally by George Charlton, its services included shaving, measuring the pate, barbering, and wigmaking. In ascending order, hair prices ranged from the cheap–goat, yak, and horse–to the most expensive–human hair. Most wigmakers imported human hair from Europe, where young peasant women grew and then sold their hair for the trade. The shop also sold products for maintaining wigs and assisting with hair care. Hygiene was a pressing issue in the eighteenth century, and the wigmaker supplied unguents, powders, and remedies for body odors, dirty hair, lice, and other ailments. Both men and women used wigs. Some were dignified; others were playful and silly.

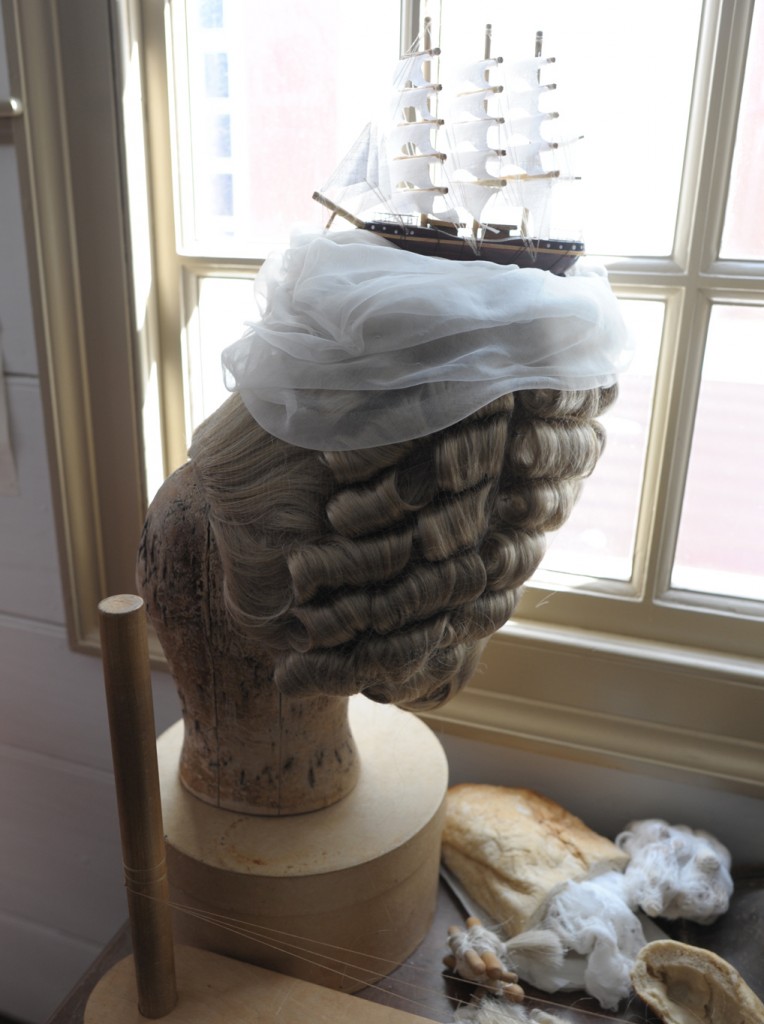

Woman’s wig with frigate based on a print source; it is mounted on a wig stand.

Wigs required maintenance and good care. Many ladies and gentlemen owned wig stands for their wigs or kept them in boxes. Within limits, a skilled wigmaker could reshape the wig and color it to the client’s specifications as fashions changed or the owner aged. For making wig dyes, workers used a variety of coloring agents from animal and vegetable sources to heavy metals such as lead, mercury and even arsenic. The latter were toxic to vermin.

A Parson’s wig.

The shop of the wigmaker was modest, but contained plenty of display wigs, showcasing the range of clientele these tradesmen might service. Although a great deal of the work of making wigs is done below stairs or away from the shop front, we were able to see the basic instruments and tools for producing the braided hair needed to construct the body of the wig. The tressing frame was portable; Betty referenced making wigs as easily on her couch at home as in the shop.

Erica ties knots of hair on a tressing frame.

The frame was constructed with a block of wood supporting two pins connected by three strings at either end. Using a diagram of the pattern, we took strands of hair and wove it on to the frame, using over-under motions to secure the hair onto the string. The pattern was outwardly simple, but the work took concentration so the hair didn’t slip off or knot. Our next step would be taking the newly completed row of hair from the tressing frame and attaching it to netting pinned to the blockhead (a head-shaped block molded to the client’s dimensions). Curling irons, dyes, powders, and pomades were the final components in dressing the wigs, much as a barber or hairdresser would curl and dress the hair on a person’s head.

Wigmaking was a low-impact activity, requiring the maker to remain stationary for a long period of time. Although the repetitious movements might be fatiguing to beginners, Betty had tied so many knots over the years that she could work quickly without thinking about what she was doing. The mental energy went to making sure the wig was progressing at an even pace, and that the hair was plaited evenly and at the right length. The level of skill varied, I imagined, depending on the type of wig ordered, and quality of hair you were working with.

Betty is weaving a knot, teaching Willie and Jesse how to do it. Her blurred hands reflects the speed with which she works using the kinetic memory acquired from years of practice. Note the curling irons that were heated on the iron stove.

Demand was uneven. Wig maintenance, shaving, new commissions, and other sales work put a strain on one’s schedule. Debbie demonstrated the technique of netting, the support structure that allowed the maker to stitch the hair onto a prepared cap. For us, making the netting proved to be far more challenging than plaiting the hair. This activity required considerable concentration. Because the wigmakers at Colonial Williamsburg previously ordered their nettings from separate sources before Betty and Debbie learned how to do it themselves, I assume it was a distinct sub trade in the colonial era as well.

With the ubiquity of wigs in the eighteenth century, it is no surprise that a day’s work might include working on multiple models, with looming deadlines. Betty notes that a single wig could take up to a month or more to make, but with more staff working on multiple tressing frames, a wig in the eighteenth century might take a week. When possible or when worn frequently, wigs were maintained every week or two, and new wigs were generally made for a customer every four to five years. The implicit understanding was that these products had a limited shelf life that guaranteed the wigmaker would have repeat customers. Of course, this market also depended on wigs remaining in fashion.

“Life Below Stairs” is on view in Colonial Williamsburg’s Museum Galleries; it shows a genre scene of servants dressing hair and primping to live above their station—much to the disgust of the washer woman on the right. (Courtesy, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

Wigs were generally expensive products. In a period during which social roles were marked visually, wigs enabled a person to signal their wealth, occupation, and attention to fashion. This social signification made wig making an indispensable trade for some people. Extensions (or queues) were available for men who wished a less costly method of maintaining the fashions of the day, but families of great means might own multiple wigs, not only for the head of household but also for family and staff. A child’s wig might cost 6-8 shillings, whereas a proper dress bob (suitable for landed gentry) cost 2 pounds, 3 shillings. Williamsburg boasted approximately eight peruke shops contemporaneous with Edward Charlton’s.

Hair extensions for men and women.

Betty concluded her discussion by remarking that wigs and wigmaking are rarely included in museum culture, to the detriment of historians interested in the trades and fashions of the past. From liveried slaves to elite patrons of society, wigs contributed to the visual landscape of colonial American society. At Colonial Williamsburg, it became clear that wigmaking was one of the few colonial trades that existed predominantly for fashion rather than necessity. Currently, the tradespeople who continue this eighteenth century tradition find themselves at risk of losing the trade. Betty put the call out for interested parties who might like to begin an apprenticeship and continue wigmaking into the next generation.

By Erica Lome, Ph.D. Program in the History of American Civilization, University of Delaware

Superb Post.thanks for share..more wait…..

AWSOME!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

cool

I only used this site because I needed research for a project…but this page is a superb help!😁👍👌👏

this is awesome

very good site that gives lots of information

this website was SO helpful for research– thank you!

😁😁😁😁😁😁😁

LOVE IT SO MUCH INFO GREAT FOR A PROJECT